The Canadian province of Ontario is undergoing an acute shortage of neurosurgeons, forcing patients to fly to US for treatment.

The Canadian province of Ontario is undergoing an acute shortage of neurosurgeons, forcing patients to fly to US for treatment.

In all 164 patients with broken necks, burst aneurysms and other types of bleeding in or outside of the brain made it to Michigan and New York State hospitals from the region since April, 2006.That includes 69 patients sent so far in fiscal 2007-2008, according to Health Ministry figures.

When Ming Quon, who teaches electrical technology at a community college, was taken to York Central Hospital, was rushed to a local hospital with complaints of sharp pain the head, he was diagnosed with a subarachnoid hemorrhage, caused by a ruptured aneurysm.

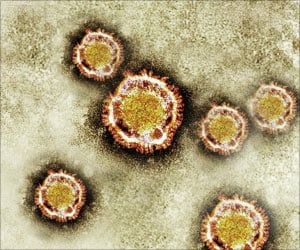

An aneurysm (AN-u-rism) is an abnormal bulge or “ballooning” in the wall of an artery. Arteries are blood vessels that carry oxygen-rich blood from the heart to other parts of the body. An aneurysm that grows and becomes large enough can burst, causing dangerous, often fatal, bleeding inside the body. If an aneurysm in the brain bursts, it causes a stroke.

Subsequently Quon underwent a craniotomy in a US hospital. It is an operation to open the skull, then a small metal clothespin-like clip is placed on the aneurysm's neck, to halt its blood supply.

He also had two endovascular coil embolizations, a minimally invasive procedure where a long, thin tube is inserted into the femoral artery near the groin, up to the aneurysm.

Advertisement

Michael P. Hughes, an official of the hospital in New York state where Quon was operated on, said his institution was seeing an increasing number of Canadian patients.

Advertisement

British Columbia has sent four patients with spinal-cord injuries to Washington State hospitals for care from May to September, 2007, though the recruitment of more staff and opening of new beds have helped alleviate the problem. Saskatchewan has sent patients to neighbouring provinces, including Alberta, for specialized neurosurgical services.

In Ontario itself, patients face barriers to receiving care at every turn, says Globe and Mail Today.

There is limited access to teleradiology and operating-room time. There are too few intensive-care beds, a short supply of neurosurgically trained intensive-care nurses to staff them and too few neurosurgeons.

In an effort to stem the tide of patients being sent to U.S. hospitals, the University Health Network has been provided an additional $4.1-million by the Ontario government to do 100 more neurosurgical cases by October, 2008.

Indeed, an expert neurosurgery panel report done on the shortage of neurosurgical services and authored by James Rutka, chairman of the division of neurosurgery at the University of Toronto, made 21 recommendations to the Ontario government in late December.

That 84-page report recommended a two-phase approach: allocating additional neurosurgical services to one hospital to address emergency out-of-country transfers immediately, and increasing capacity in more centres in Ontario.

Health Minister George Smitherman's press secretary, Laurel Ostfield, said "the government is currently awaiting further advice from the team who drafted the report on the best way to use the recommendations in our combined efforts to improve patient care for Ontarians."

Over the past three years, she said the government's track record has been to implement 80 per cent of recommendations received from expert panel reports.

James Rutka, chairman of the division of neurosurgery at the University of Toronto, was appointed by the provincial government to head the expert neurosurgery panel. In his just released report, Dr. Rutka noted there was an "alarming trend" of sending Ontarians out of province for neurosurgery care.

"It is poor patient care to transfer people who need emergency care out of province or to make anyone who needs neurosurgery wait longer than they should and risk doing them harm," Dr. Rutka wrote in his 84-page report. Transferring patients out of province should only be done in exceptional circumstances, he said.

Some observations in the report:

About 65 neurosurgeons provide neurosurgery each year to more than 30,700 Ontarians in 13 hospitals in larger urban areas.

Neurosurgical conditions are a major cause of disability, morbidity and mortality that results in high costs to individuals, their families and society.

Dr. Rutka made 21 recommendations to fix the problem, including:

The heads of 13 hospital neurosurgical units should develop clear and simple criteria for determining when a patient needs a neurosurgical consultation and may need to be transferred to a neurosurgical unit. As well, they should develop a simple protocol for looking after minor head injuries in the emergency room. This information should be provided to every hospital in Ontario and posted in emergency rooms.

Hospitals with Level 3 and 4 (the most acute) neurosurgical units should dedicate resources, including operating rooms, equipment and staff for unplanned emergency cases.

Neurosurgical centres should provide updated bed information to CritiCall (an emergency-referral service for physicians) electronically at least twice daily.

The Ontario government should increase its full-time neurosurgeon-to-population ratio from 1 per 187,077 to the more appropriate level of 1 per 150,000. If that ratio were accepted, 15 additional neurosurgeons would be required.

Source-Medindia

GPL/L