- Living Liver Donor Mortality: Where Do We Stand? - (http://www.clevelandclinic.org/bioethics/documents/liverdonormortality.pdf)

- Living-donor liver transplantation in adults - (http://bmb.oxfordjournals.org/content/94/1/33.full#sec-13)

- Live Donors in Liver Transplantation - (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/s001650850800231x)

About

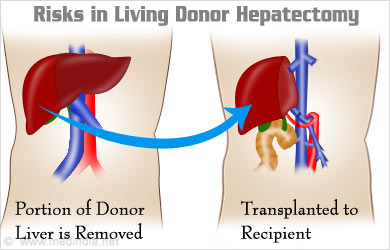

Adult-to-adult living donor liver transplant is practiced worldwide, with the majority of activity in the Far East (Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, China) and the Indian Subcontinent. In India, 90% of liver transplants are from living donors (usually family members or “close emotional relationships”), whereas in the United States, only 5% of livers transplanted are from living donors and the remaining 95% are from deceased donors. Cultural barriers to the acceptance of brain death and organ donation has driven living donor liver transplant in Eastern countries and most of the surgical technical innovations to perfect these operations (donor liver removal surgery and liver transplant surgery) has been developed in Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong. These critical advances have improved the results of living donor liver transplant (one year patient survival rates of 81% in the US and 93% in Hong Kong) and decreased the risks to the donor significantly.

However, the risks of morbidity and even mortality are not zero for living liver donation. A generally accepted range of the risk of dying as a result of a living donor liver segment removal is between 0.2-2.0%, based on currently available literature. The problem with these estimates, however, is that there exists no international database of living donor liver transplant outcomes, so the actual risk of death from donating a piece of one’s liver for transplant is unknown. Donor deaths are likely underreported because mandatory reporting of such information is only in place in Europe and (only recently) the United States.

The mortality risk for living donor hepatectomy (liver segment removal) is less in large volume transplant centers with extensive experience, but there have been a few donor deaths even in the best of American hospitals (and a recently reported donor death in a high volume liver transplant center in India). The fear of donor mortality greatly curtails the volume of living donor liver transplants performed in the US, largely because of litigation concerns. Surprisingly, many transplant hospital websites (including some in the US) do not mention the risk of death in their information pages on donor hepatectomy.

The risk of morbidity (temporary illnesses, surgical complications, or long term non fatal disabilities such as stroke ) related to living donor hepatectomy is anywhere between 1.3% (in highly experienced centers ) to 60% within the first three months of surgery. Fortunately, these morbidities are almost always successful treated with medicines, radiologic interventions, or minor surgery and do not result in excessive rehospitalization stays. Morbidities can range from simple urinary tract infections to more comlplicated bile duct complications related to the surgery, but they rarely result in long term heallth problems. Two suicides after liver donation have been reported in the US and it is unclear how much of a role the emotional stress of the donor surgery played into their suicidal ideations.

Potential liver donors need to be meticulously screened for their medical, surgical, social and psychological fitness. Absence of emotional or financial coercion must first be guaranteed before proceeding with the rest of the donor evaluation. Medical comorbidities such as heart disease, lung disease, underlying liver disease (especially fatty liver), and kidney disease must be assessed and, ideally, completely ruled out to minimize the risk benefit ratio of the surgery as much as possible. Social factors, such as family support for convalescence, should be evaluated and facilitated. A psychiatric or psychologic assessment should also be performed prior to donation.

The donor and transplant recipient must have compatible blood types and must be of compatible size. The latter is a critical consideration in partial liver transplant because, although the liver possesses the remarkable ability to regenerate, at least 30% of the entire liver mass must be present to sustain life. Anything less than this liver volume will not be able to regenerate, leading to liver failure and death. The current practice is to take no more than 60% of a donor’s liver for transplant, leaving the donor with a 40% liver mass that will successfully regenerate to nearly 100% within a month. If there is a significant size discrepancy between donor and recipient (i.e., if the donor is smaller than the recipient) then the surgery is at high risk for failure because the recipient will not have a sufficiently regenerative liver mass.

Despite the risk of morbidity and mortality, living liver donors usually live uneventful lives after complete recovery from their surgery and, in fact, have longer life expectancies than the average because they were selected as very healthy individuals in the first place. They also enjoy a profound sense of emotional well being as a result of their gift. The long term success of living donor liver transplant for the recipient is on par with whole liver transplant from deceased donor organs, or just over 70% survival in five years compared to 0% survival without a liver transplant. Live donor liver transplant, while more expensive than deceased donor transplant, has been shown to be cost effective in many European and American studies.

Causes of Living Liver Donor Hepatectomy Complications

The documented causes of living liver donor mortality include massive liver insufficiency/failure, bleeding, pulmonary embolus, stroke, infection, and adverse drug reaction. Liver failure is the most common cause of donor death and can happen if the donor had unrecognized underlying liver disease and could not support a 60% reduction in liver mass. Great care must be taken to monitor the donor’s condition perioperatively and postoperatively to ensure timely intervention should a life threatening complication occur.

Morbidities related to donor hepatectomy can be surgical or medical and include bleeding, bile duct leak, intraabdominal abscess, wound infection, deep vein thrombosis leading to pulmonary embolism, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, stroke, heart attack, or liver insufficiency/failure. Although any of these complications could potentially be fatal, they are usually discovered in a timely fashion and treated successfully.

Symptoms of Living Liver Donor Hepatectomy

Symptoms of liver insufficiency include extreme lethargy leading to coma, nausea, easy bleeding or bruising, and total body swelling (edema). Massive bleeding can present as light headedness, weakness, shortness of breath, and a feeling of impending doom. Other complications have their organ specific manifestations, such as a productive cough for a pneumonia or pain or burning upon urination for a urinary tract infection, etc.

Diagnosis of Living Liver Donor Hepatectomy

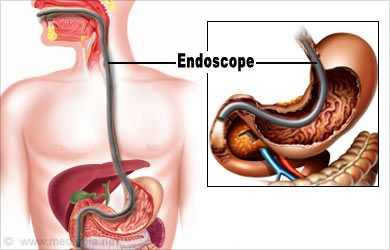

Immediate operative complications are monitored for using serial blood testing (liver function tests, blood counts, and electrolytes) and imaging (usually ultrasound as a preliminary investigation). More advanced imaging must be performed to diagnose suspected problems, such as an ERCP (Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio Pancreatogram) for bile duct problems or angiogram for vascular problems.

Routine blood and urine tests direct the need for any further tests to detect liver insufficiency, infections, coronary or cerebrovascular problems, or postoperative intraabdominal fluid collections.

Treatment for Living Liver Donor Hepatectomy

Surgical complications often either require additional surgery or minimally invasive procedures by the interventional radiologists. Hepatologists or Gastroenterologists can perform endoscopy both for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes (e.g., place a stent into an injured bile duct). Medical complications are treated accordingly with proper antibiotics for infections and other systems specific issues. Liver failure in a donor after hepatectomy will either resolve on its own with supportive care or will require liver transplant.