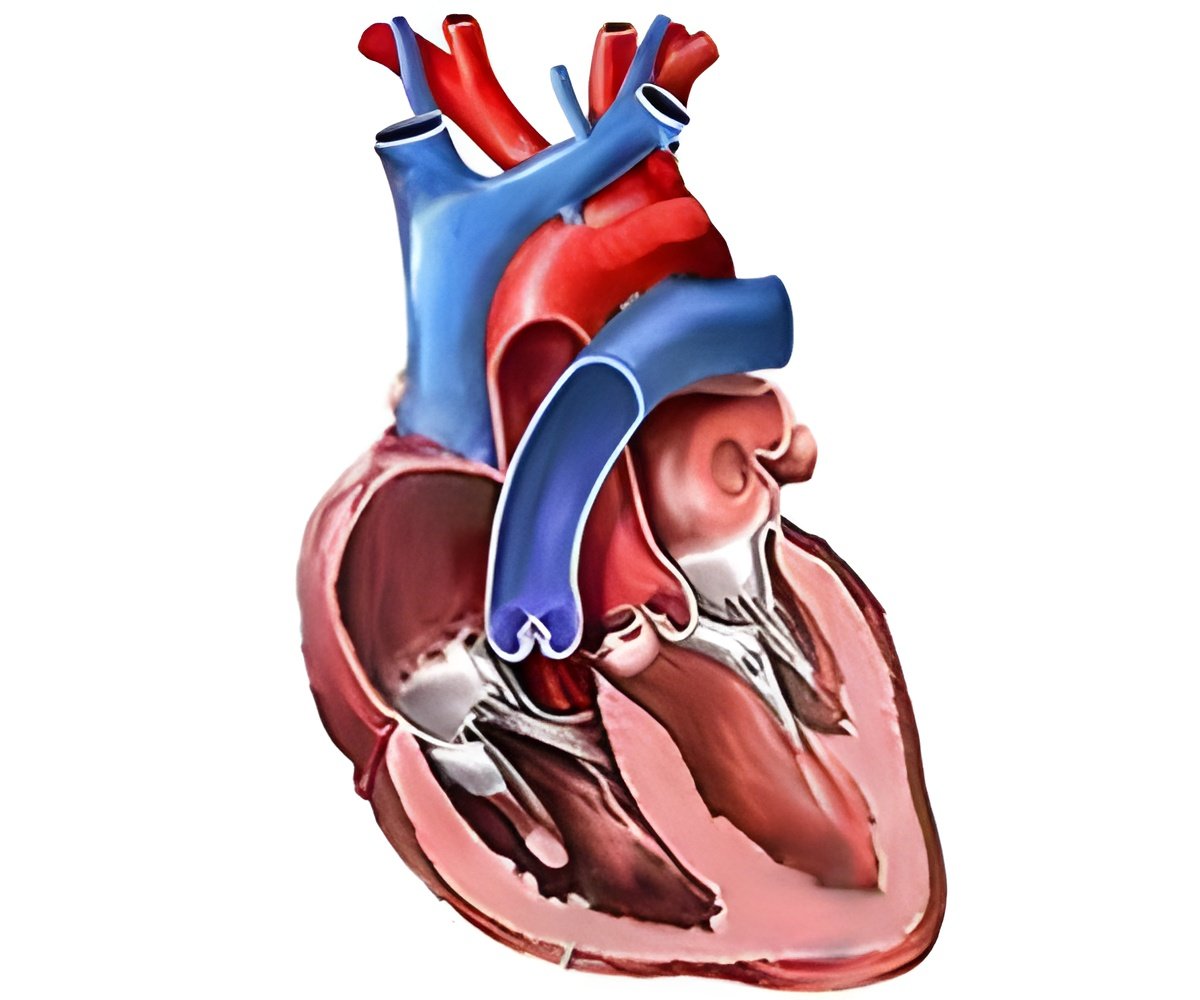

Most people would consider a big heart to be a good thing. However, for heart disease experts, it is often a sign of serious disease.

Several years ago, Dr. Megeney noticed that heart muscle cells undergoing this kind of abnormal growth had many similarities with cells that are beginning to undergo an orderly form of cell suicide called programmed cell death. In the current research paper, Dr. Megeney and his team show that blocking the proteins that control this form of cell death also blocks abnormal heart muscle thickening.

Dr. Megeney and his team exposed rats to a number of different drugs that each induce abnormal heart muscle thickening. The rats were then given a form of experimental gene therapy to block cell suicide proteins in the heart. Three weeks later, the rats that received the experimental therapy had much smaller heart muscle cells (37 percent smaller than those that did not receive the therapy), and smaller hearts overall. In fact, the disease model rats that received the experimental therapy seemed just as healthy as normal rats.

"Our research shows, for the first time, that heart muscle cells use the same molecular machinery for unhealthy growth as they would use to commit suicide," said Dr. Megeney, a senior scientist at OHRI and associate professor at uOttawa. "This may seem quite surprising to some people, but it fits with a growing body of research showing that cell death proteins can play many other roles in the body."

"Our research also shows, for the first time, that if we block the activity of cell suicide proteins in the heart, we can block abnormal heart muscle thickening in animal models," he added. "Although more research needs to be done, we think this may represent a promising new strategy for treating certain forms of heart disease. We are already investigating possible approaches to achieve this in humans, and we have identified some promising leads."

"This research is very important scientifically, and potentially clinically as well," said Dr. Duncan Stewart, a practicing cardiologist who is also CEO and scientific director of OHRI, vice-president of research at The Ottawa Hospital, professor at uOttawa. "This research is particularly applicable to certain genetic forms of heart disease, as well as to hypertension, which affects about 40 percent of the adult population."

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert