A team of researchers have now discovered how the 'good' bacteria in our gut communicates with our own cells, thereby establishing the basis of a successful relationship

We all rely on trillions of bacteria in our gut to break down certain components of our diet. One example is phytate, the form phosphorus takes in cereals and vegetables. Broken down phytate is a source of vital nutrients, but in its undigested form it has detrimental properties. It binds to important minerals preventing them being taken up by the body, causing conditions like anaemia, especially in developing countries. Phytate also leads to excess phosphorus leaching into the soil from farm animal waste, and feed supplements are used to minimise this.

But despite the importance of phytate, we know very little about how it is broken down in our gut.To address this Dr Stentz and colleagues screened the genomes of hundreds of different species of gut bacteria. They found, in one of the most prominent gut bacteria species, an enzyme able to break down phytate. In collaboration with Norwich Research Park colleagues at the University of East Anglia, they crystallised this enzyme and solved its 3D structure.

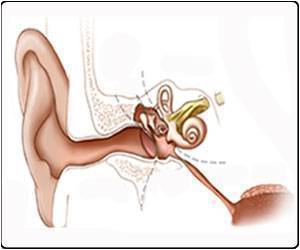

They then went on to characterise the enzyme, showing it was highly effective at processing phytate into the nutrients the body needs. The bacteria package the enzyme in small 'cages', called outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) which allow phytate in for nutrient processing but prevent it being destroyed by our own protein-degrading enzymes. This releases nutrients, specifically phosphates and inositol, which can be absorbed by our own bodies, as well as the bacteria.

Source-Eurekalert