DEFINITION

Lupus is a disorder of the autoimmune disease. In autoimmune

diseases, the body harms its own healthy cells and tissues. This

leads to inflammation mage to various body tissues. Lupus can affect

many parts of the body, including the joints, skin, kidneys, heart,

lungs, blood vessels, and brain. Lupus is characterized by periods

of illness, called flares, and periods of wellness (remission).

Although lupus is used as a broad term, several kinds of lupus

exist.

Systemic lupus erythematosus is the most

common form of the disease. The symptoms of SLE may be mild or

serious.

Discoid lupus erythematosus refers to a skin

disorder in which a red, raised rash appears on the face, scalp, or

elsewhere. The raised areas may become thick and scaly and may cause

scarring. The rash may last for days or years and may recur. A small

percentage of persons with discoid lupus have or develop SLE.

Drug-induced lupus refers to a form of lupus caused

by specific medications. Symptoms are similar to those of SLE and

typically resolve when the drug is stopped.

Neonatal

lupus is a rare form of lupus affecting newborn babies of women

with SLE or certain other immune-system disorders. At birth, the

babies have a skin rash, liver abnormalities, or low blood counts,

which resolve entirely over several months. However, babies with

neonatal lupus may have a serious heart defect. Physicians can now

identify most at-risk mothers, allowing for prompt treatment of the

infant at or before birth. Neonatal lupus is very rare, and most

infants of mothers with SLE are entirely healthy.

At

present, no cure for lupus exists. However, lupus can be very

successfully treated with appropriate drugs, and most persons with

the disease can lead active, healthy lives.

ETIOLOGY

Lupus is a

complex disease, the cause of which is unknown. In addition, some

autoantibodies join with substances from the body's own cells or

tissues to form molecules called immune complexes. A buildup of

these immune complexes in the body also contributes to inflammation

and tissue injury in persons with lupus. Researchers do not yet

understand all the factors that cause inflammation and tissue damage

in lupus.

SYMPTOMS

Each person's experience

with lupus is different, though patterns exist that permit accurate

diagnosis. Symptoms can range from mild to severe and may come and

go over time.

Common symptoms of lupus include painful or

swollen joints, muscle pain, unexplained fever, skin rashes, and

extreme fatigue. A characteristic skin rash may appear across

the nose and cheeks-the so-called butterfly or malar rash. Other

rashes may occur elsewhere on the face and ears, upper arms,

shoulders, chest, and hands.

Other symptoms of lupus include

chest pain, unusual hair loss, sensitivity to the sun, anemia, and

pale or purple fingers or toes from cold and stress (Raynaud's

phenomenon). Some persons also experience headaches, dizziness,

depression, or seizures. New symptoms may continue to appear years

after the initial diagnosis, and different symptoms can occur at

different times.

The following systems in the body also can

be affected by lupus.

Kidneys:

Inflammation of the kidneys can impair their ability to get rid of

waste products and other toxins from the body effectively. Usually

no pain is associated with kidney involvement, though some persons

may notice that their ankles swell. Most often the only indication

of kidney disease is an abnormal urine or blood test. Kidneys:

Inflammation of the kidneys can impair their ability to get rid of

waste products and other toxins from the body effectively. Usually

no pain is associated with kidney involvement, though some persons

may notice that their ankles swell. Most often the only indication

of kidney disease is an abnormal urine or blood test.

Lungs: Some persons with lupus

develop pleuritis. Persons with lupus also may get pneumonia. Lungs: Some persons with lupus

develop pleuritis. Persons with lupus also may get pneumonia.

Central nervous system : In some

persons, lupus affects the brain or central nervous system. This can

cause headaches, dizziness, memory disturbances, vision problems,

stroke, or changes in behavior. Central nervous system : In some

persons, lupus affects the brain or central nervous system. This can

cause headaches, dizziness, memory disturbances, vision problems,

stroke, or changes in behavior.

Blood

vessels: Blood vessels may become inflamed, affecting the way

blood circulates through the body. The inflammation may be mild or

severe. Blood

vessels: Blood vessels may become inflamed, affecting the way

blood circulates through the body. The inflammation may be mild or

severe.

Blood: Persons with lupus may

develop anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia. Some persons with

lupus may have abnormalities that cause an increased risk for blood

clots. Blood: Persons with lupus may

develop anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia. Some persons with

lupus may have abnormalities that cause an increased risk for blood

clots.

Heart: In some persons with lupus, myocarditis, endocarditis,

or pericarditis can occur, causing chest pains or other symptoms.

Lupus can also increase the risk of atherosclerosis

Heart: In some persons with lupus, myocarditis, endocarditis,

or pericarditis can occur, causing chest pains or other symptoms.

Lupus can also increase the risk of atherosclerosis

Despite

the symptoms persons with lupus can maintain a high quality of life

overall. One key to managing lupus is understanding the disease and

its impact.

Learning to recognize the warning signs of a

flare can help a person take steps to ward it off or reduce its

intensity. Many persons with lupus experience increased fatigue,

pain, a rash, fever, abdominal discomfort, headache, or dizziness

just before a flare.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of lupus

can be difficult. It may take months or even years for physicians to

piece together the symptoms to diagnose this complex disease

accurately.

No single test can determine whether a person

has lupus, but several laboratory tests may aid in the diagnosis.

Most persons with lupus test positive for ANA.

However, there are a number of other causes of positive ANA results,

including infections and other rheumatic or immune

diseases-occasionally they even are found in healthy adults. The ANA

test simply provides another clue for the physician to consider in

making a diagnosis.

In

addition, blood tests for individual types of autoantibodies exist

that are more specific to persons with lupus, though not all persons

with lupus test positive for these, and not all persons with these

antibodies have lupus. These antibodies include anti-DNA,

anti-Sm, anti-RNP, anti-Ro (SSA), and anti-La (SSB). These

antibody tests may help in the diagnosis of lupus.

Some

tests are used less frequently but may be helpful if the cause of a

person's symptoms remains unclear. A biopsy of the skin or

kidneys may be indicated if those body systems are

affected. A test for syphilis or the anticardiolipin

antibody may also be useful. Positive test results do not mean that

a person has syphilis; however, the presence of this antibody may

increase the risk of blood clotting and can increase the risk of

miscarriages in pregnant women with lupus. Again, all these tests

merely serve as tools in making a diagnosis.

Other

laboratory tests are used to monitor the progress of the disease

once it has been diagnosed. A complete blood count, urinalysis,

blood chemistries, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate test can

provide valuable information. Another common test measures the blood

level of a group of substances called complement. Persons with lupus often

have increased erythrocyte sedimentation rates and low complement

levels, especially during flares of the disease.

Persons

diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have

autoantibodies in their blood years before any symptoms appear,

according to an article in the October 16, 2003, issue of The New

England Journal of Medicine.

The early detection of

autoantibodies may facilitate the recognition of those persons who

will develop SLE and may allow physicians to monitor them before the

disease might otherwise be noticed.

THINK ABOUT

THESE

A cataract cannot return

because all or part of the lens has been removed. However, in some

people who have had extracapsular surgery or phacoemulsification,

the lens capsule becomes cloudy after a year. It causes the same

vision problems as a cataract does. To correct this, laser

capsulotomy can be performed. In laser (YAG) capsulotomy a laser

(light) beam is used to make a tiny hole in the capsule to let light

pass. This surgery is painless and does not require stay in the

hospital.

Full Source Title:American Journal of

Medicine

Abstract

PURPOSE:We sought to assess the nephritogenic

antibody profile of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and to determine which

antibodies were most useful in identifying patients at risk of

nephritis. METHODS: We studied 199 patients with SLE, 78 of whom had

lupus nephritis. We assayed serum samples for antibodies against

chromatin components (double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid [dsDNA],

nucleosome, and histone), C1q, basement membrane components (laminin,

fibronectin, and type IV collagen), ribonucleoprotein, and

phospholipids. Correlations of these antibodies with disease

activity (SLE Disease Activity Index) and nephropathy were assessed.

Patients with no initial evidence of nephropathy were followed

prospectively for 6 years. RESULTS: Antibodies against dsDNA,

nucleosomes, histone, C1q, and basement membrane components were

associated with disease activity (P <0.05). In a multivariate

analysis, anti-dsDNA antibodies (odds ratio [OR] = 6; 95% confidence

interval [CI]: 2 to 24) and antihistone antibodies (OR = 9.4; 95%

CI: 4 to 26) were associated with the presence of proliferative

glomerulonephritis. In the prospective study, 7 (6%) of the 121

patients developed proliferative lupus glomerulonephritis after a

mean of 6 years of follow-up. Patients with initial antihistone (26%

[5/19] vs. 2% [2/95], P = 0.0004) and anti-dsDNA reactivity (6%

[2/33] vs. 0% [0/67], P = 0.048) had a greater risk of developing

proliferative glomerulonephritis than patients without these

autoantibodies.

CONCLUSION: In addition to

routine anti-dsDNA antibody assay, antihistone antibody measurement

may be useful for identifying patients at increased risk of

proliferative glomerulonephritis.

Full Source Title:Arthritis and Rheumatism

Abstract:

OBJECTIVE: To

determine the degree to which changes in C3 and C4 precede or

coincide with changes in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

activity, as measured by 5 global activity indices, the physician's

global assessment (PGA), modified SLE Disease Activity Index

(M-SLEDAI), modified Lupus Activity Index (M-LAI), Systemic Lupus

Activity Measure (SLAM), and the modified British Isles Lupus

Assessment Group (M-BILAG), and to evaluate the association between

changes in C3 and C4 levels and SLE activity in individual organ

systems. RESULTS: Lupus flares occurred at 12% of visits based on

the PGA, 19% based on the M-SLEDAI, 25% based on the M-LAI, 13%

based on the SLAM, and 12% based on the M-BILAG. Recent changes in

C3 and C4 levels were not associated with flares based on 3 of the 5

activity indices. Flares defined by the M-LAI were more frequent

when there was a concurrent decrease in C3 (odds ratio [OR] 1.9, 95%

confidence interval [95% CI] 1.1-3.1) or C4 (OR 2.1, 95% CI

1.3-3.6). Higher flare rates, as defined by the SLAM, were

associated with previous increases in C3 (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.0-2.6)

and C4 (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.2-3.9). When individual organ systems were

analyzed, decreases in C3 and C4 were associated with a concurrent

increase in renal disease activity (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.4-3.5 and OR

1.9, 95% CI 1.1-3.4, respectively). Decreases in C3 were also

associated with concurrent decreases in the hematocrit (OR 4.6, 95%

CI 1.7-12.3), platelet (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.5-4.1), and white blood

cell (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3-3.6) counts. Previous increases in C3

levels were associated with a decrease in platelets (OR 1.7, 95% CI

1.1-2.7). A decrease in C4 was associated with a concurrent decrease

in the hematocrit level (OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.3-7.5) and platelet count

(OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.0-2.5).

CONCLUSION: Decreases in complement levels were

not consistently associated with SLE flares, as defined by global

measures of disease activity. However, decreasing complement was

associated with a concurrent increase in renal and hematologic SLE

activity

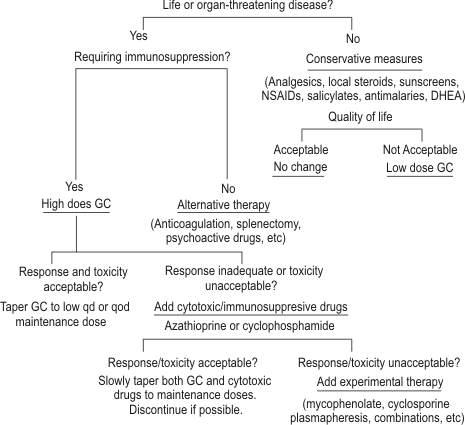

TREATMENT OF SLE

CONSERVATIVE MANAGEMENT

Arthritis, Arthralgia, and

Myalgia

Arthritis, arthralgia, and myalgia are the most

common manifestations of SLE. Severity ranges from mild to disabling. For

patients with mild symptoms, administration of analgesics,

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or salicylates may

provide adequate relief, although none of these is as effective as

glucocorticoids.

In many SLE patients, musculoskeletal symptoms are

not well controlled by salicylate or NSAID therapy. A trial of

antimalarial drugs may be useful in such

individuals.

Hydroxychloroquine is the preferred

antimalarial agent in the United States (chloroquine may be more effective

but has a higher incidence of retinal toxicity: quinacrine is often

effective but rarely can cause aplastic anemia). The usual dose of

hydroxychloroquine for SLE patients with arthritis is 400 mg

daily. If response does not occur within 6 months, the patient

can be considered a nonresponder and the drug stopped. If

hydroxychloroquine is used for more than 6 months or chloroquine is used

for more than 3 months, regular examination by an ophthalmologist for

retinal damage is mandatory. If antimalarials are effective, the

maintenance dose should be reduced periodically if possible, or the drug

should be withdrawn when a patient is doing well, because the retinal

toxicity is cumulative.

Some patients with arthritis or arthralgia

do not benefit from NSAIDs or salicylates with or without antimalarials.

Administration of dihydroandrosterone (DHEA), 100 to 200

mg daily, lowers activity of SLE in some patients, including arthritis/arthralgias.

Methotrexate in weekly oral or parenteral

doses of 10 to 20 mg may also be considered, because there are reports of

its efficacy in some cases.

However, none of these

interventions is as reliable as glucocorticoid therapy in suppressing

lupus arthritis and arthralgia. If quality of life is seriously

impaired by pain (or by the deformities that develop in about 10 percent

of individuals with lupus arthritis), the physician should consider

institution of low-dose glucocorticoids, not to exceed 15 mg each

morning.

Rare patients require high-dose

glucocorticoids or even cytotoxic drugs. Such interventions should be

avoided if possible. In fact, if arthritis is the major

manifestation of disease that compels the physician to choose high-dose

immunosuppressive treatments, it may be preferable to use around-the-clock

non-narcotic or narcotic analgesics to control pain, rather than to risk

life-threatening side effects of aggressive immunosuppression.

Cutaneous

Lupus

As

many as 70 percent of patients with SLE are photosensitive..Patients

should begin with preparations that block UVA and UVB.

Sunscreens can be locally irritating (especially those

that contain PABA); patients may need to try several preparations to find

one that is not irritating.

Local

glucocorticoids, including topical creams and ointments and

injections into severe skin lesions, are also helpful in lupus dermatitis.

[ Patients with disfiguring (discoid) or extensive lesions should be seen

by a dermatologist, because management of severe lupus dermatitis can be

difficult.

Antimalarial agents are useful in some

patients with lupus dermatitis, whether the lesions are those of SLE,

subacute cutaneous lupus, or discoid lupus. Antimalarials have multiple

sunblocking, anti-inflammatory, and immunosuppressive effects. They also

bind melanin and serve as sunscreens, and they have antiplatelet and

cholesterol-lowering effects. All these properties may be beneficial to

patients with SLE.

Responses to chloroquine and quinacrine are

usually demonstrable within 1 to 3 months; responses to hydroxychloroquine

may require 3 to 6 months. Antimalarials may be steroid sparing.

Recommended initial doses of antimalarials are hydroxychloroquine, 400 mg

daily, chloroquine phosphate, 500 mg daily, and quinacrine, 100 mg daily.

Higher doses can be given for brief periods (2 to 4 weeks). After disease

is well controlled, the drugs can be slowly tapered. Daily doses can be

reduced, or the drug can be given less frequently (e.g., a few days each

week). The combination of hydroxychloroquine (or chloroquine) and

quinacrine is probably synergistic and can be used in patients refractory

to single-drug therapy.

Toxicities of these agents are important

but infrequent in comparison with other agents used to treat SLE. Retinal

damage is the most important; it can occur in up to 10 percent of patients

receiving chronic chloroquine therapy but is much less frequent in those

receiving hydroxychloroquine. Regular ophthalmologic examinations

with appropriate special testing identify retinal changes early.

If changes occur, antimalarial therapy should be stopped or the daily dose

decreased. This strategy substantially lowers the incidence of clinically

important retinal toxicity. Retinopathy is rare in patients treated with

quinacrine.

For individuals with lupus rash resistant to

antimalarials and other conservative strategies, etretinate has been

beneficial. The retinates are teratogenic, cause cheilitis in

most patients, and elevate cholesterol and triglyceride levels in some.

Patients resistant to antimalarials and retinates may require systemic

glucocorticoids, which improve lupus skin lesions of any type. Additional

treatments, which should be considered experimental for dermatologic

lupus, include dapsone, thalidomide, and cytotoxic drugs.

Dapsone has been used in discoid lupus,

urticarial vasculitis, and bullous LE lesions with some success. It has

significant hematologic toxicities (including methemoglobinemia,

sulfhemoglobinemia, and hemolytic anemia) and can occasionally worsen the

rashes of LE. Some steroid-resistant cases have improved when treated with

cytotoxic drugs such as azathioprine or methotrexate.

Successful treatment of refractory lupus rashes with

thalidomide has been reported. Development of peripheral

neuropathy associated with thalidomide is not uncommon. This highly

teratogenic drug is available on special request from the manufacturer,

with appropriate assurances that the patient cannot become pregnant.

Fatigue

and Systemic Complaints

Fatigue is common in patients with SLE and may be the

major disabling complaint. It reflects multiple problems, including

depression, sleep deprivation, and fibromyalgia. Fever and weight loss, if

mild, can be managed with the conservative approaches

outlined in the preceding paragraphs. When severe, systemic

glucocorticoid therapy is necessary.

Serositis

Episodes of chest and abdominal pain may be

secondary to lupus serositis. In some patients, complaints respond to

salicylates, NSAIDs (indomethacin may be best), or antimalarial therapies,

or to low doses of systemic glucocorticoids, such as 15

mg/day In others, systemic glucocorticoids must be given in high

doses to achieve disease remission.

RECENT ADVANCES

TABLE 1

-- APPROACHES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF SYSTEMIC LUPUS

ERYTHEMATOSUS

|

| Agent |

Target |

| Anti-CD40L (gp 39)

mAbs |

T-cell activation/T-cell-B-cell

collaboration |

| CTLA-4Ig |

|

| 3E10 mAb vaccine |

Inhibition of Ab

production |

| LJP 394: B-cell

toleragen |

Inhibition of Ab

production |

| rHuDNAse |

Inhibition of Ab

production |

| Anti-C5 mAb |

Complement activation/immune

complex deposition |

| Anti-IL-10 mAbs |

Cytokine

activation/modulation |

| AS101 (anti-IL-10) |

Cytokine

activation/modulation |

| Gene therapy |

Cytokine

activation/modulation |

| Thalidomide (anti-tumor necrosis

factor-alpha) |

Cytokine

activation/modulation |

| IVIg |

Immunomodulation |

| Bindarit |

Immunomodulation |

| Plasmapheresis |

Immunomodulation |

| *Mycophenolate

mofetil |

Immunomodulation |

| Immunoadsorption |

Immunomodulation |

| 2CdA |

Immunomodulation |

| Fludaribine |

Immunomodulation |

| Methimazole |

Immunomodulation |

| Stem cell

transplantation |

Stem cells |

| Immunoablative

treatment |

|

| DHEA |

Sex hormones |

| Selective estrogen receptor

modulators |

Sex

hormone | |

|

*Mycophenolate mofetil has been tried

as a treatment for several autoimmune diseases, on the basis of the

positive experience with this drug in recipients of solid-organ

transplants. The parent compound is hydrolyzed to mycophenolic acid,

an inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, which blocks

several steps in the effector arm of the immune system. In mice with

lupus, mycophenolate mofetil prolonged overall survival and delayed

the onset and severity of nephritis.7 In small studies of patients

with lupus nephritis that was resistant to cyclophosphamide,

mycophenolate mofetil appeared to be effective in controlling renal

disease.

Treatment of Lupus Nephritis

The standard of care for the treatment of

aggressive forms of the disorder is the administration of

intravenous cyclophosphamide.3 In addition to oral

glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide is given in monthly

intravenous pulses for at least six consecutive months. In

one study, exacerbations of lupus nephritis were reduced when

intravenous cyclophosphamide was given every three months for an

additional two years.

Chan et al. present the results of a

study in Hong Kong in which patients with diffuse proliferative

lupus nephritis were treated with prednisolone and mycophenolate

mofetil or with prednisolone and cyclophosphamide followed by

prednisolone and azathioprine.The study provides evidence

that treatment with mycophenolate mofetil is as effective as and has

fewer side effects than sequential treatment with cyclophosphamide

and azathioprine. There are several reasons for caution in

generalizing these findings to other patients with diffuse

proliferative lupus glomerulonephritis.

*Prophylactic anticoagulation therapy is not

justified in patients with high titer anticardiolipin antibodies

with no history of thrombosis.

*However, if

a history of recurrent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism is

established, long-term anticoagulant therapy with international

normalized ratio (INR) of approximately 3 is needed.

Antiphospholipid syndrome

The

syndrome occurs most commonly in young to middle-aged adults;

however, it also can occur in children and the elderly. Among

patients with SLE, the prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies is

high, ranging from 12% to 30% for anticardiolipin

antibodies, and 15% to 34% for lupus anticoagulant

antibodies. In general, anticardiolipin antibodies occur

approximately five times more often then lupus anticoagulant in

patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. This syndrome is

the most common cause of acquired thrombophilia, associated

with either venous or arterial thrombosis or both. It is

characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies,

recurrent arterial and venous thrombosis, and spontaneous abortion.

Rarely, patients with antiphospholipid syndrome may have fulminate

multiple organ failure, or catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome.

This is caused by widespread microthrombi in multiple vascular beds,

and can be devastating. Patients with catastrophic antiphospholipid

syndrome may have massive venous thromboembolism, along with

respiratory failure, stroke, abnormal liver enzyme concentrations,

renal impairment, adrenal insufficiency, and areas of cutaneous

infarction.

According to the international consensus

statement, at least one clinical criterion (vascular thrombosis,

pregnancy complications) and one laboratory criterion (lupus

anticoagulant, antipcardiolipin antibodies) should be present for a

diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome.

The

hallmark result from laboratory tests that defines antiphospholipid

syndrome is the presence of antibodies or abnormalities in

phospholipid-dependent tests of coagulation, such as dilute

Russell viper venom time. There is no consensus for

treatment among physicians. Overall, there is general agreement that

patients with recurrent thrombotic episodes require

life-long anticoagulation therapy and that those with recurrent

spontaneous abortion require anticoagulation therapy and low- dose

aspirin therapy during most of gestation.

|

|

| CONCLUSIONS

|

|

An

appreciation of the many facets of SLE is essential, including a

recognition of the current limit of our knowledge about the disease

and its management. A better understanding of the pathogenesis of

SLE promises to provide much information about the nature and the

role of the immune response in this and other diseases.

|

|