"The globalization of trade is the most important development for those who would use biological weapons against plants," says Deen. Bioterrorists can cause havoc, he says, by contaminating just a fraction of a crop-international trade restrictions will do the rest.

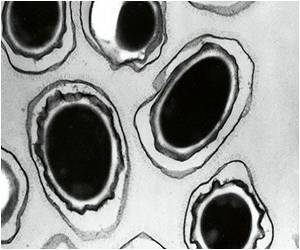

Under the World Trade Organization's "phytosanitary" rules, a minor disease outbreak can take an entire crop off the export market. Take karnal bunt, a relatively mild-if highly infectious-wheat smut that turns grain black, sticky and inedible. When the smut blew into Arizona from Mexico two years ago, 32 countries, including China, banned US wheat imports in one day. The US spent hundreds of millions of dollars to eradicate the fungus and save its $5 billion annual wheat exports. This episode helped to fuel current US fears of anti-crop weapons, as it dawned on plant pathologists that a deliberate attempt to sabotage US grain exports might not look very different.

So much for motives, but what about means? Building a biobomb aimed at plants would be a far less ambitious undertaking than designing one to take out humans ("All fall down," New Scientist, 11 May 1996, p 32). A large-scale biological attack on people needs a carefully "weaponised" germ, to ensure that pathogens normally spread by close physical contact can be transmitted through the air and still be infectious. Plant viruses, bacteria and fungi, on the other hand, are already adept at seeking out and destroying victims that don't move. They are conveniently adapted to be spread by the wind and insect vectors.

And although genetically engineered crop bioweapons may sound scary, there's little need for them. "You can always find a natural plant pathogen as nasty as anything you could create," says Anne Vidaver, head of the Center for Biotechnology at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. One exception might be an otherwise benign virus engineered to produce a human toxin-harmless for the plant, but a nasty surprise for whoever eats it.

Naturally occurring fungi such as smuts and rusts are far more likely to be a crop bioterrorist's weapon of choice, says Vidaver. Fungal spores are tough, and can infect crops in a wider range of growth stages and environmental conditions than most bacteria and viruses. Fungi can also produce potent toxins, so even a small infestation can make an entire harvest toxic.

Pathogens for plant bioterrorism are a lot less trouble to breed than those aimed at humans because they need not be highly specific to the target, or even destroy that much of a crop to have an impact. Just a small greenhouse full of the crop and a few pathogens collected from local crops-which are likely to be different from those to which the crops in your target country are immune-would suffice. A plant biological weapon would even be safer to manufacture than one designed to attack humans, which can always turn on its creators.

All the same, preparing a crop biobomb would not be a trivial undertaking. For instance, the spores would have to be specially formulated to prevent clumping, and to protect them from ultraviolet light. But with a little luck and a little technical expertise, a weapon could be cooked up in someone's backyard.

They could even get away with it. Spray anthrax from a light aircraft over bustling Washington DC and someone is going to notice. Spread spores of karnal bunt over the lonely plains of Kansas and in all likelihood nobody will see. Agriculture may be the world's biggest industry, and the most vital for human well-being, but it is also one of the least secure. "You could do enough damage to achieve your goal just by bringing in a suitcase full of vials of the pathogen and strolling past a field with an atomiser," says Wheelis.

Soft Target

What's more, natural outbreaks of novel plant diseases have multiplied dramatically over the past decade as food, seed and people cross borders at ever-increasing rates. In North America, 25 plant viruses alone are listed as new or re-emerging, while the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization in Paris has an "alert list" of 31 fungi, bacteria and viruses that are threatening to invade Europe. "With all these novel infections happening naturally," says Vidaver, "it may not be obvious if an outbreak is deliberate."

One way to deter would-be bioterrorists is to deny them deniability. "If we could say where a pathogen comes from, we could narrow things down," says Schaad. To that end, his unit at the USDA has collected thousands of plant bacteria from around the world. The next step is to DNA fingerprint the bacteria so that when a suspicious outbreak occurs, plant pathologists will quickly be able to work out where the errant pathogen came from. There are no libraries for fungal and viral pathogens. "We spends millions collecting genetic varieties of crops, but nothing on collecting their pathogens," says Schaad.

In September, President Bill Clinton announced that $215 million would be spent to upgrade a USDA agricultural quarantine laboratory on Plum Island off the coast of New York State, to deal with threats to US agriculture, including plant pathogens. The lab will be equipped to analyse pathogens sent in from any suspicious outbreak. Assuming, of course, that someone notices such an outbreak in the first place. Farmers are not obliged to notify the authorities when an outbreak occurs. An attack "could occur without us knowing it, because we really don't have the tools in place to detect [it]", Floyd Horn, head of the USDA's research service, told the US Senate last month.

"We need automated systems that will enable people to get immediate identification of pathogens in the field," says Schaad. Such systems would rely on DNA and protein analyses similar to those being developed to detect biological weapons aimed at people ("Bioarmageddon", New Scientist, 19 September 1998, p 42).

No amount of technology will help, of course, if there are not enough plant pathologists to police the crops. Even as the threat of natural and unnatural disease outbreaks increases, says Bob Forster of the University of Idaho in Kimberley, there is a declining number of people who can identify diseases in the field.

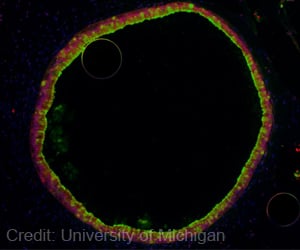

Assuming you have identified a crop bioterrorist attack, how do you limit the damage? Fungicides can stop or slow the spread of a fungal disease. But for crops infected with bacteria or viruses, usually the only option is to burn them, and eradicate any insect vectors, which can be extremely difficult and costly.

An alternative approach would be to rapidly replace contaminated crops with those that are resistant to the pathogen. Plant breeding companies are investing millions characterizing plant genes. In a few years, when a new disease strikes, it may well be possible to pull out the right resistance gene and breed it into the crop that is under attack. The USDA has already identified 26 genes that protect against the barley stripe rust that was wiping out the crop in the northwest of the US in 1995. But it takes resources and time to breed new characteristics into crops and get them out to the farms, so this line of defense will only be available to the wealthy West, and at best can only reduce long-term damage. Consumer opposition to genetically modified crops could also make this approach uneconomical.

Nor is there any guarantee that there will always be a resistance gene available. Take wheat streak mosaic, a virus that is spreading in North America and can cause catastrophic crop losses. Despite extensive research, no one has ever found a resistant variety. Alternative strategies do exist-such as using genes from other species-but ultimately any attempt to engineer resistance into plants only works until bioterrorists find a new pathogen. With such strike and counter-strike, "the world could get itself into a bioweapons arms race", warns Brian Halweil of the World watch Institute, an agricultural and environmental think tank in Washington DC.

According to Vidaver, the best strategy is to reduce the threat of crop bioterrorism in the first place. This goal, she says, can be achieved in part through limiting the spread of infections by abandoning the uniformity of modern farm fields in favour of diverse plant varieties and more crop rotation. Modern American farms, with their huge expanses of one variety of wheat, maize or alfalfa, are "a disaster waiting to happen", she warns.

With the ever-increasing threat of natural plant diseases, investing in improved vaccines and disease diagnosis, and a move away from monocultures could start to make good economic sense. The irony will be if North American fears of crop bioterrorism force its farmers to adopt methods that coincidentally give it more of an edge over its global competitors-even if the terrorists never strike.

|