What is Liver Transplantation?

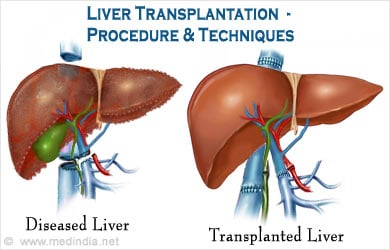

Liver transplantation or hepatic transplantation replaces a liver that is diseased with a healthy liver from another person (this liver in the recipient is also called allograft) and can come as part liver or as whole liver.

The first human liver transplantation was first performed in 1963 by Dr. Thomas Starzl of Denver, Colorado, United States. But until 1970 liver transplant surgery remained experimental with a one year patient survival of only 25%. Today the one-year patient survival continues to improve and on an average is 80–85%. Of all the solid organ transplant surgeries, the liver transplant surgery remains the most formidable procedure with higher complication rates than other transplants.

There are essentially two types of liver transplants:

- Living donor liver transplant (“LDLT”)

- and Deceased donor liver transplant (“DDLT”) from a dead person

Orthotopic and Heterotopic Transplantation

What, then, is an Orthotopic Liver Transplant? Orthotopic means “In the same place”. The patient’s diseased liver is removed entirely and replaced with a donor liver in the same place.

Kidney and pancreas transplants are heterotopic procedures (the donor organs are placed in the pelvis), but they are rarely referred to as such.

A LDLT is technically an orthotopic procedure (the donor liver segment replaces the diseased liver removed from the patient) but “Orthotopic Liver Transplant” generally refers to whole organ deceased donor transplants. Patients who meet with brain death and are declared properly as such can become organ donors if the family consents. DDLT is performed much more widely in the US compared to developing countries like India, where Living donor liver transplants predominate. Currently in India, one third of liver transplants are from deceased donors.

The results for both LDLT and DDLT are quite good, with an 85-90% one year survival and 70% five year survival for both. This is compared to NO survival without a liver transplant. The complication rates in LDLT are higher (for example, a biliary complication rate of 30% with living donor versus 15% with deceased donor), but the overall outcomes are equivalent. The LDLT surgery is exquisitely complicated because the donated segment of liver has smaller blood vessels and bile ducts. There is also a small, but real, risk of a donor’s death, so the surgeons and transplant teams performing LDLT must be extremely well trained, talented, disciplined and experienced.

Techniques of Liver Transplant Surgery

The techniques involved in LDLT and DDLT are in principal the same. In an adult to adult LDLT, a segment of liver equivalent to 60% of the total liver mass is removed from the donor. In an adult to child LDLT, only 25% of the liver suffices. In DDLT, the entire liver is removed and usually the whole organ is transplanted into the recipient. However, in certain ideal cases, the deceased donor liver can be “split” and transplanted into two recipients (the smaller piece going to a child and the larger piece going to another child or small adult).

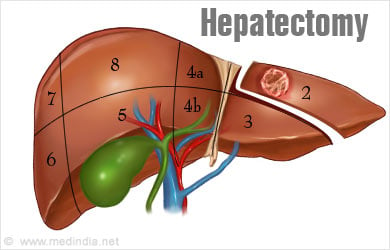

During the LDLT donor “hepatectomy” (surgical removal of the liver), extreme care must be taken to minimize blood loss or injury to critical structures such as bile ducts and blood vessels, and the exact anatomy of these structures should be studied as best as possible prior to even starting the operation.

A “total hepatectomy” is performed in the case of DDLT and care must be taken not to injure any critical structures and to properly preserve the organ prior to transplant. The organ recovery surgery (previously referred to as “harvesting” but this term has fallen out of favor: “organ retrieval”, “organ recovery” or “organ procurement” are all acceptable alternatives) often involves recovery of multiple organs including heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, pancreas and intestines, depending on the availability of transplant center expertise, so many different surgical recovery teams might be present. The deceased donor is declared brain dead (two independent clinical exams and confirmatory “apnea tests”) and consent from the family is obtained prior to proceeding with multiorgan recovery.

The brain dead patient’s heart and lungs are maintained with mechanical and pharmacologic assistance so even though the patient is legally and medically dead (brain death is irreversible because there is no longer blood flow to the brain and all brain stem functioning has ceased), the heart is still beating at the time of recovery surgery. All of the recovery teams start their organ dissections simultaneously and when it is time to remove the organs from the body, the heart is recovered first, then lungs, then liver, pancreas and kidneys. The heart and lungs can only be outside of the body for 4-6 hours prior to transplant, whereas the liver should be transplanted within 12 hours and the kidneys in less than 24 hours (less than 12 hours is ideal). Special organ preservation solution is used to flush the organs so that they do not become too injured while on ice without their blood supply.

The liver transplant procedure itself lasts anywhere between 4-10 hours and involves five major steps.

The recipient’s diseased liver is first removed in its entirety. The recipient total hepatectomy, is in fact, the most dangerous part of the surgery because the liver is not functioning properly so the blood does not coagulate well and very large blood vessels such as the inferior vena cava and portal vein must be carefully attended to in order to avoid excessive bleeding. “Hemostasis”, or control of bleeding, is critical during the recipient hepatectomy and requires excellent surgical technique and skilled anesthesia support to rapidly replace blood products (if needed) and maintain “hemodynamic stability” (i.e., normal pulse and blood pressure).

Anhepatic Stage - The second phase, the “anhepatic” phase commences after the old liver is removed and before the new liver is reconnected to its blood supply. Many metabolic and bleeding issues need to be managed by the anesthesiologists at this point. The surgeon must quickly connect the veins draining blood from the liver and reestablish portal vein flow into the liver.

Reperfusion Stage - The “reperfusion” phase occurs when portal blood inflow and hepatic venous outflow is re-established. This third phase can be accompanied by hemodynamic instability (low blood pressure), high potassium levels (leading to irritation of the heart) and excessive bleeding (depending on the quality of surgical technique). Sometimes it can take several minutes to hours for the new liver to begin functioning properly to synthesize blood clotting factors and to clear acid out of the bloodstream.

Arterial Reperfusion Stage – The fourth phase, when the hepatic artery is “anastomosed” (surgically connected) and opened up for more blood to flow into the liver.

Fifth phase - When the bile duct is anastomosed. The fourth and fifth phase are usually relatively calm moments during the transplant, but care must be taken to perform these connections properly to avoid complications such as hepatic artery thrombosis or biliary leak or stricture.

As a result of improved surgical and anesthetic techniques, effective immunosuppression and anti-infection medicines and practice of true multidisciplinary care, liver transplantation in well selected recipients and donors is extremely successful in the modern transplant era. Both LDLT and DDLT are accepted standards of care in the treatment of end stage liver disease.

Postoperative Care

First 24 to 48 hrs - Once the surgical operation is over the patient is usually kept in a special intensive care unit where well trained specialist team of intensive care doctors and nurses takes care of the patient to ensure that they are kept stable hemodynamically (blood pressure, oxygenation, fluids and urine output are balanced and maintained. Function of the new liver is monitored closely by blood tests and ultrasound examinations. The liver function tests should demonstrate a trend towards normal during this time. On rare occasions (<2% of the time), the new liver does not start working at all (“primary nonfiction”) or there might be a surgical complication such as hepatic artery thrombosis that requires immediate retransplant.

Normally for the first 24 to 48 hours the patient is kept on ventilator (a special machine that keeps the lung expanded and the body well oxygenated) and the patients are kept deeply sedated until it is time to remove the ventilator. Once the ventilator is removed, the patient is fully conscious and can start eating and moving around slowly.

During this period a limited number of relatives maybe allowed to see the patient.

Postoperative Days (PODs) 3-10 days – Once the patient is extubated (ventilator removed) and stable, he or she can be transferred out of the ICU to the regular liver transplant ward. Here, nurses and doctors ensure adequate pain control and a normal recovery path, regularly monitoring liver function tests and immunosuppression drug levels. The bladder catheter is removed on Postoperative Day #3 and usually the surgical drains are all removed prior to discharge home. The sutures closing the skin incision are not removed until 2-3 weeks after the operation and this is done in the outpatient clinic.

When the patient’s liver function tests (and all other labs) normalized and they are ambulating and tolerating a regular diet, the Transplant Pharmacist and/or Transplant Social Worker have teaching sessions with the patient and family to ensure that everyone understands the many different drugs that must be taken, their purpose, their doses and their potential side effects. Also, general discharge advice about avoiding infection and when to return to the outpatient clinic are imparted.

Follow Liver Transplantation Part 2: Complications and Results to Read more...