11-year-old Canadian boy taken away for forced chemotherapy is to be returned to his family. All of them want no more of the therapy saying it is futile, but doctors want it to go on.

11-year-old Canadian boy taken away for forced chemotherapy is to be returned to his family. All of them want no more of the therapy saying it is futile, but doctors want it to go on.

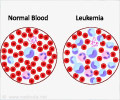

The boy’s parents, who were in a Hamilton courtroom Tuesday, reached an agreement with the Children's Aid Society that their son will go home at the end of his current bout of chemotherapy.His family has also agreed to bring the boy, who suffers from an aggressive form of leukemia, back for further treatments.

The family has also been granted special funding to seek second and third opinions on his prognosis.

"Now the question is is whether the treatment that's proposed is in the best interests for this child," Marlys Edwardh, the family's lawyer said. "And we'll deal with that separately."

The family will be back in court in June 16 to resolve their continued appeal of CAS jurisdiction.

"Right now we had to play by their fiddle and that's fine," the boy's father said outside court.

Advertisement

But medical officials insisted that he needed the treatment, saying the boy had a good chance of recovery and that he wasn't capable of making his own life and death decisions.

Advertisement

Chemo has taken most of his hair, left him with skin rashes and mouth sores, and he's unable to walk on his own.

When told last week he needed more chemo or he would face death within six months, the boy refused.

His family supported his decision, but doctors insisted he go through the therapy.

A judge ruled the boy cannot make an informed decision and ordered him into CAS care to ensure he gets the treatment, which began last week.

Bioethicists call the decision to force chemo on him "heavy-handed" and "worrisome."

On Monday, some bioethicists said they were concerned about the decision and worried that other parents' wishes might be superseded by health-care practitioners who assume they know best.

"If a doctor says [therapy] is in your best interest and you say you don't want it, within our laws, ethically and legally, that's fully acceptable," said Kerry Bowman of the University of Toronto's Joint Centre for Bioethics.

"And in this case that's kind of turned upside down. Best interests have taken over as opposed to what the family believes, and I think there's a lot of ethical tension here, and I think it's pretty worrisome."

There may be factors in the case that haven't been publicized and that could have influenced the decision to ignore the boy's wishes, but Bowman said he was a bit surprised by the decision.

"It looks very heavy-handed to me and it's got a lot of implications, because we have lots of children throughout the country in institutions and parents often have a different view of what treatment should be than physicians do," he said.

"You have a medical system that says, 'This is how we treat this illness, whether you like it or not.'"

The Hamilton case is not particularly rare or unusual and is "the kind of thing that we struggle with in health care all the time," said Brendan Leier, a clinical ethicist with the University of Alberta and the Stollery Children's Hospital in Edmonton.

"I know for a fact there are many more cases like this one that you don't see widely publicized," Leier said.

Although officials had decided the boy wasn't capable of making his own decisions and that his parents were essentially making the wrong choice for their son, the patient was arguably the best equipped to predict how chemotherapy would affect his body given that he'd been through it before, Leier said.

"This kid is now an expert on what going through chemo entails and this is where it becomes, for me, ethically problematic," he said.

"This kid knows better than anyone else how this is affecting his life, so who is a doctor or a judge to say that this is really in his best interests?"

Although it's a complicating factor that the boy has fetal alcohol syndrome and takes special education classes, Leier said the boy was still capable of understanding what more chemotherapy would do to him.

"He understands what it feels like to have chemo, he understands what it is to go through that and have all the ill-health effects, and it's very difficult to argue that any more intellectual capacity would enhance his judgment," he said.

A handful of similar cases play out every year at Toronto's Hospital for Sick Children although they usually end with a negotiated solution that everyone can live with, said Christine Harrison, director of the hospital's bioethics department.

Harrison said she believed that children should be fully involved with the decision process and their opinions and feelings need to be heard, even if they don't get the final say in their care.

"It's respectful of them as a person. They're the one who's having the treatment imposed on them, and certainly it's important that all people who are capable of having a voice have a voice," she said.

Leier said there's a danger in forcing treatment on a patient and whether it actually ends up helping or making their plight worse.

"Is it medically efficacious to treat someone against their will, and what role does the will play in actually treating yourself and actually healing yourself — think that's a very interesting question."

Source-Medindia

GPL/L