Studies of the adolescent brain often focus on the negative effects of teenagers' reward-seeking behaviour.

‘Teenagers do not necessarily have better memory, in general, but rather the way in which they remember is different.’

However, the study found that this tendency may be tied to better learning as well as a critical feature of adolescence and the maturing brain. "We identified patterns of brain activity in adolescents that support learning -- serving to guide them successfully into adulthood," Shohamy added. For the study, the team involved 41 teenagers and 31 adults and scanned the brains of each participant with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while they were performing the learning tasks.

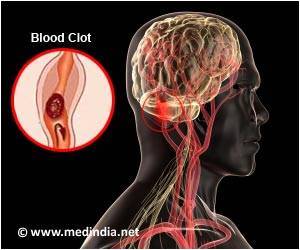

The fMRI analysis revealed an uptick in hippocampal (brain's memory centre) activity for teenagers -- but not adults -- during reinforcement learning -- a reward signal that helps the brain learn how to repeat the successful choice again. Moreover, that activity seemed to be tightly coordinated with activity in the striatum -- a critical component of the brain's reward system.

The researchers also slipped in random and irrelevant pictures of objects into the learning tasks, such as a globe or a pencil. When asked later on, both adults and teens remembered seeing some of the objects. However, only in the teenagers the memory of the objects was associated with reinforcement learning.

"The findings showed that teenagers do not necessarily have better memory, in general, but rather the way in which they remember is different," Shohamy said. The results of this research were published in the journal Neuron.

Advertisement