Threatened by the possible spread of an Ebola, which respects no borders, Africa is divided between a handful of countries equipped to withstand an outbreak and many more which would be devastated, reveal experts.

The Ebola epidemic has taken 3,000 lives in west Africa, cruelly laying bare the frailties of underdeveloped infrastructure in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, according to World Bank president Jim Yong Kim.

But he sounded a note of optimism at a recent news conference in Sydney, noting that Ebola can be defeated with sound, simple medical care.

"Our own sense is if you get those pretty fundamental basic things in place, then we can have a very high survival rate," he said.

That prognosis is echoed by Tom Kenyon, director for global health at the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

"We don't need large numbers of specialists or expatriate doctor specialists," he said after a mission in the three most badly affected nations in early September.

Advertisement

Yet even this is hard for the three worst-hit countries. They averaged only one doctor for every 100,000 inhabitants even before the epidemic claimed the lives of scores of doctors and nurses. Now they face the collapse of their health care systems.

Advertisement

"Yesterday, we received 60 cases, and they keep coming," Alfred Gaye, a nurse at the hospital, told AFP.

At the other end of the continent geographically, and a world away in terms of development, South Africa has 80 times the density of medical staff of Liberia.

The country is "pretty well prepared" for an outbreak, according to Lucille Blumberg, deputy director of the National Institute for Communicable Diseases.

South Africa boasts 11 public hospitals capable of treating Ebola, in addition to numerous private clinics.

"Ebola can spread here just as well as anywhere else but... here you could protect the people by isolating them easier, preventing them from moving around," said Joseph Teeger, a South African family doctor.

- Worrying lack of resources -

The picture is grim in Benin and Niger, poverty-stricken neighbours of Nigeria which has reported a handful of Ebola deaths but has declared the outbreak within its borders under control.

"We are not prepared for thousands of patients. But we will be prepared to accommodate two, three or four cases," said Akoko Kinde Gazar, the public health minister in Benin, a country with just 12 specialist beds for Ebola.

Niger would need eight regional centres to have any serious chance of coping with an outbreak, says Chaibou Hallarou, a spokesman for the Office of Surveillance and Epidemic Response.

It has just one Ebola centre and one mobile team based in the capital.

Ebola preparedness is weak outside of big population centres right across Africa. And the unwillingness to set up facilities in more remote areas is not just a question of funding.

Suspicious locals have attacked health workers in the countryside, a trend which hit a gruesome nadir in the murder of eight Ebola educators in southern Guinea in mid-September.

So although Ivory Coast has set up 16 Ebola units staffed by hundreds of trained health-care workers across the country, the authorities have decided against remote clinics.

"When we saw what happened in Guinea and Liberia, we decided to put these treatment centres in our hospitals," said Daouda Coulibaly, an epidemiologist at the National Institute of Public Health.

- 'Arrogant' doctors and nurses -

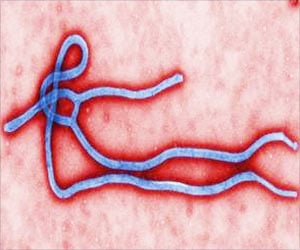

Ebola spreads through contact with infected bodily fluids, so family members and healthcare workers looking after the sick are particularly at risk.

Faced with an outbreak which has the potential to spread fast, people's willingness to follow safety guidelines is essential, yet Africans are not always inclined to respect their doctors and nurses.

"Health-care delivery in Ghana is not patient friendly. Some doctors and nurses -- the loud minority -- are arrogant and disrespectful to patients," local specialist Joseph Boateng told AFP.

"Patients find it difficult to talk to their doctors and nurses about their illnesses. Patients are not encouraged to participate in their own care."

However, the opposite tends to be true in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which are both well-versed in dealing with Ebola outbreaks and have evolved well-trained workforces.

"There is not a lot of fear of the medical system, people are willing to seek help," said Trevor Shoemaker, leader of Uganda's CDC.

In Gabon, too, previous outbreaks have also contributed to awareness, "be it political, personal or concerning the health of the population", says Eric Leroy, director of the International Centre for Medical Research.

Ebola is no respecter of international boundaries, and experts agree that nations need to work together.

While examples of such solidarity remain rare, small but growing numbers of Africans at one end of the continent are looking out for those at another.

South African epidemiologist Kathryn Stinson, who has volunteered for a mission in Sierra Leone in October, hopes to provide the model for such cooperation.

"We are sharing a continent with others who are bearing the consequence of a foundering health system that is, in turn, betraying its own people," she wrote in a local newspaper ahead of her departure.

"While fully understanding the risks, it's time to put my money where my mouth is."

Source-AFP