Scientists at have conducted a joint cell and animal study that has revealed one important contributor to the severe anemia that result from malaria, often causing death.

Scientists at Johns Hopkins, Yale and other institutions have conducted a joint cell and animal study that has revealed one important contributor to the severe anemia that result from malaria, often causing death.

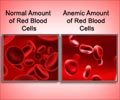

The culprit is a protein cells make in response to inflammation called MIF, which appears to suppress red blood cell production in people whose red blood cells already are infected by malaria parasites.The parasite that causes malaria - known as plasmodium - is carried through blood by mosquito bites, and in parts of the world where mosquitoes thrive, millions are infected, most of them by early childhood. Once in the bloodstream, plasmodium invades liver and red blood cells and makes more copies of itself. Eventually, as red cells break and free plasmodium to infect other cells, and as the body's immune system works to kill infected cells, the total number of red blood cells drops, causing anemia.

But not everyone infected with malaria develops severe, lethal anemia. And there are cases where patients who have been cured of infection still develop severe anemia. This report provides the rationale for a simple, genetic test to sort out which children may be most susceptible to this lethal complication of malarial infection and to identify treatments targeted to them especially, the study's authors suggest.

"This is important because in places where malaria is endemic, drug treatment resources are scarce," says the study's primary author, Michael A. McDevitt, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor of medicine and hematology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

"There are many difficulties with blood transfusion safety and access in Africa, especially in rural areas where most of the malaria-related deaths occur," says McDevitt. "That led us to search for a better way to identify those most at risk and a better way to treat the disease," he says. The study, published online April 24 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, adds to a growing amount of evidence that an individual's unique genetic makeup can affect the prevalence and outcome of diseases, in this case the individual risk of malarial anemia.

A number of human proteins, including MIF (which stands for migration inhibitory factor), were long suspected to cause malarial anemia because they are known to reduce red blood cell counts as part of the body's normal response to such inflammatory conditions as rheumatoid arthritis or some cancers.

Advertisement

When infected with plasmodium, mice genetically engineered to lack MIF experience less severe anemia and are more likely to survive. Without MIF around to prevent blood cells from maturing, the mice appear better able to maintain their oxygen carrying capacity and don't lose as much hemoglobin, the protein found in red blood cells responsible for binding to oxygen molecules.

Advertisement

The research team also found different versions of "promoter" DNA sequences next to the MIF gene that control how much MIF protein a cell makes in response to infection. One version of the MIF promoter leads to less MIF protein made, while cells containing another version of the MIF promoter make much more MIF protein. Differences in the MIF promoter also have been linked to the severity of other inflammatory diseases.

The researchers continue to collaborate in an effort to develop drugs that might block MIF and treat severe anemia in malaria patients.

Source: Eurekalert