The manner in which bacteria protect themselves from their own toxins was explained by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

The new study described one of these protective mechanisms, potentially paving the way for new classes of antibiotics that cause the bacteria's toxins to turn on themselves.

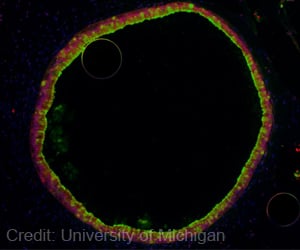

Scientists determined the structures of a toxin and its antitoxin in Streptococcus pyogenes, common bacteria that cause infections ranging from strep throat to life-threatening conditions like rheumatic fever.

In Strep, the antitoxin is bound to the toxin in a way that keeps the toxin inactive.

"Strep has to express this antidote, so to speak. If there were no antitoxin, the bacteria would kill itself," said Craig L. Smith, first author of the study.

With that in mind, Smith and colleagues may have found a way to make the antitoxin inactive. They discovered that when the antitoxin is not bound, it changes shape.

Advertisement

In this case, the toxin is known as Streptococcus pyogenes beta-NAD+ glycohydrolase, or SPN.

Advertisement

The research paper appeared Feb. 9 in the journal Structure.

Source-ANI