Bariatric surgery can improve many aspects of health physically. Still, the alleviation of mental health problems should not be expected, as it persists in teens five years after surgery despite substantial weight loss.

‘Mental health problems persist in teens even after five years of bariatric surgery despite substantial weight loss. Hence, a multidisciplinary bariatric team should offer long-term mental health support after surgery.’

Read More..

The number of bariatric procedures in adolescents with severe obesity is rapidly increasing. Previous research has shown that bariatric surgery is safe and effective in adolescents and the 2018 guidelines from the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery state that this type of surgery should be considered the standard of care in adolescents with severe obesity. Read More..

However, a substantial minority of adolescents with severe obesity have coexisting mental health problems, and little is known about the long-term mental health consequences of bariatric surgery. Those who seek surgery might hope to see symptoms improve as a result of weight loss, but long-term outcomes are relatively unknown. A 2018 study found no alleviation of mental health disorders when adolescents were questioned two years following surgery. The new study is the first to take a longer-term view and to use records of psychiatric drug prescriptions and of specialist care for mental health disorders, in combination with self-reported data.

"The transition from adolescence to young adulthood is a vulnerable time, not least in adolescents with severe obesity," says Dr. Kajsa Järvholm from Skåne University Hospital, Sweden. "Our results provide a complex picture, but what’s safe to say is that weight-loss surgery does not seem to improve general mental health. We suggest that adolescents and their caregivers should be given realistic expectations in advance of embarking on a surgical pathway and that as adolescents begin treatment, long-term mental health follow-up and support should be a requirement."

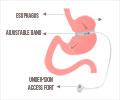

In the study, participants were aged 13-18 years before treatment started. The researchers recruited 81 Swedish adolescents with severe obesity who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery between 2006 and 2009. Their average BMI before treatment was 45. As a control group, the authors recruited 80 adolescents with an average BMI of 42, who were given conventional lifestyle obesity management, including cognitive behavioral therapy and family therapy.

Data on psychiatric drugs dispensed and specialist treatment for mental and behavioral disorders before treatment, and five years afterward were retrieved from national registers with individual data. In addition, participants in the surgical group reported their mental health problems (such as self-esteem, mood, binge eating, and other eating behaviors) using a series of questionnaires before surgery, and one, two, and five years afterward. The number of participants who completed questionnaires declined to 75 by year five.

Advertisement

Five years after treatment, self-reported measures of mental health improved slightly in the surgical group. Self-esteem improved from an average score of 19 pre-surgery (from a possible score of 0-30, with a higher score indicating higher self-esteem) to a score of 22 at five years, while binge eating, emotional eating, and uncontrolled eating were all reported less often.

Advertisement

The overall mood had not improved at the five-year follow-up. The average score was unchanged, and 72% (54 of 75) of the adolescents and young adults questioned scored below the average of those of a similar age in the general population.

The authors highlight several limitations to their study. For example, it was not randomized, and there were not enough adolescents with the same degree of severe obesity to perfectly match the control and surgical groups. Adolescents in the surgical group had a slightly higher BMI before treatment and were slightly older, so psychosocial problems may have been more prevalent. The small sample size might have prevented the researchers from detecting other important differences between the groups.

Writing in a linked Comment, lead author Dr. Stasia Hadjiyannakis (who was not involved in the study) from the University of Ottawa, Canada, says: "The high burden of mental health risk in youth with severe obesity needs to be better understood. Bariatric surgery does not seem to alleviate these risks, despite resulting in significant weight loss and other physical health benefits. Those living with obesity encounter weight bias and discrimination, which in turn can negatively affect mental health. We must advocate for and support strategies aimed at decreasing weight bias and discrimination to begin to address mental health risk through upstream action."

Source-Eurekalert