A new study in mice gives the first direct evidence of why the connection between heart disease and belly fat – also known as visceral fat exists and a look at how it might be broken.

It has long been known that overweight people have a higher risk of heart attacks, strokes and other problems that arise from clogged, hardened arteries.

And now, a new study in mice gives the first direct evidence of why the connection between heart disease and belly fat – also known as visceral fat exists and a look at how it might be broken.Researchers from University of Michigan Cardiovascular Centre have reported the direct evidence of a link between inflammation around the cells of visceral fat deposits, and the artery-hardening process of atherosclerosis.

The researchers also show that a medication often given to people with diabetes can be used to calm that inflammation, and protect against further artery damage.

The study was led by Daniel Eitzman, M.D., a cardiologist, laboratory scientist and associate professor in the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at the U-M Medical School and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

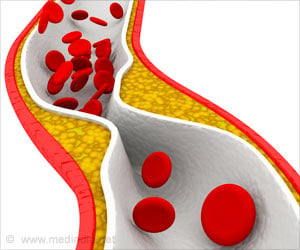

The researchers were interested to see if there might be any link between the inflammation and atherosclerosis - the formal name for the process by which blood vessels become stiff, narrowed and lined with plaque formations that can trigger the development of blood clots.

This process, which occurs throughout the body, sets the stage for most heart attacks and strokes. Scientists and clinicians now realize that it is based on inflammation – the abnormal reaction of the body’s immune system to its own tissue — and in the damage that immune-system cells and molecules can inflict.

Advertisement

Since normal mice don’t develop atherosclerosis, the team had to turn to a strain that had been developed to be especially prone to high cholesterol and hardened arteries.

Advertisement

Some of the fat-transplant ApoE-negative mice received transplants of visceral fat, which forms in the belly around the major organs, while others received transplants of subcutaneous fat – the type that’s found just under the skin throughout the body.

The mice that received the visceral fat transplants developed atherosclerosis at a much-accelerated rate, and experienced the same type of inflammation as the leptin-deficient mice had. Meanwhile, those that received subcutaneous fat did not experience an increase in atherosclerosis despite having increased inflammation. The mice that had the “sham” operations developed neither inflammation nor increased atherosclerosis.

“There appeared to be an interaction between the macrophages causing the inflammation in the visceral fat, and the process of atherosclerosis,” Eitzman said.

Finally, the team attempted to calm the inflammation and curb the atherosclerosis by treating the mice with pioglitazone – a member of the class of drugs called thiazolidinediones or TZDs that are often used to treat diabetes.

The study is published in the journal Circulation.

Source-ANI

LIN/M