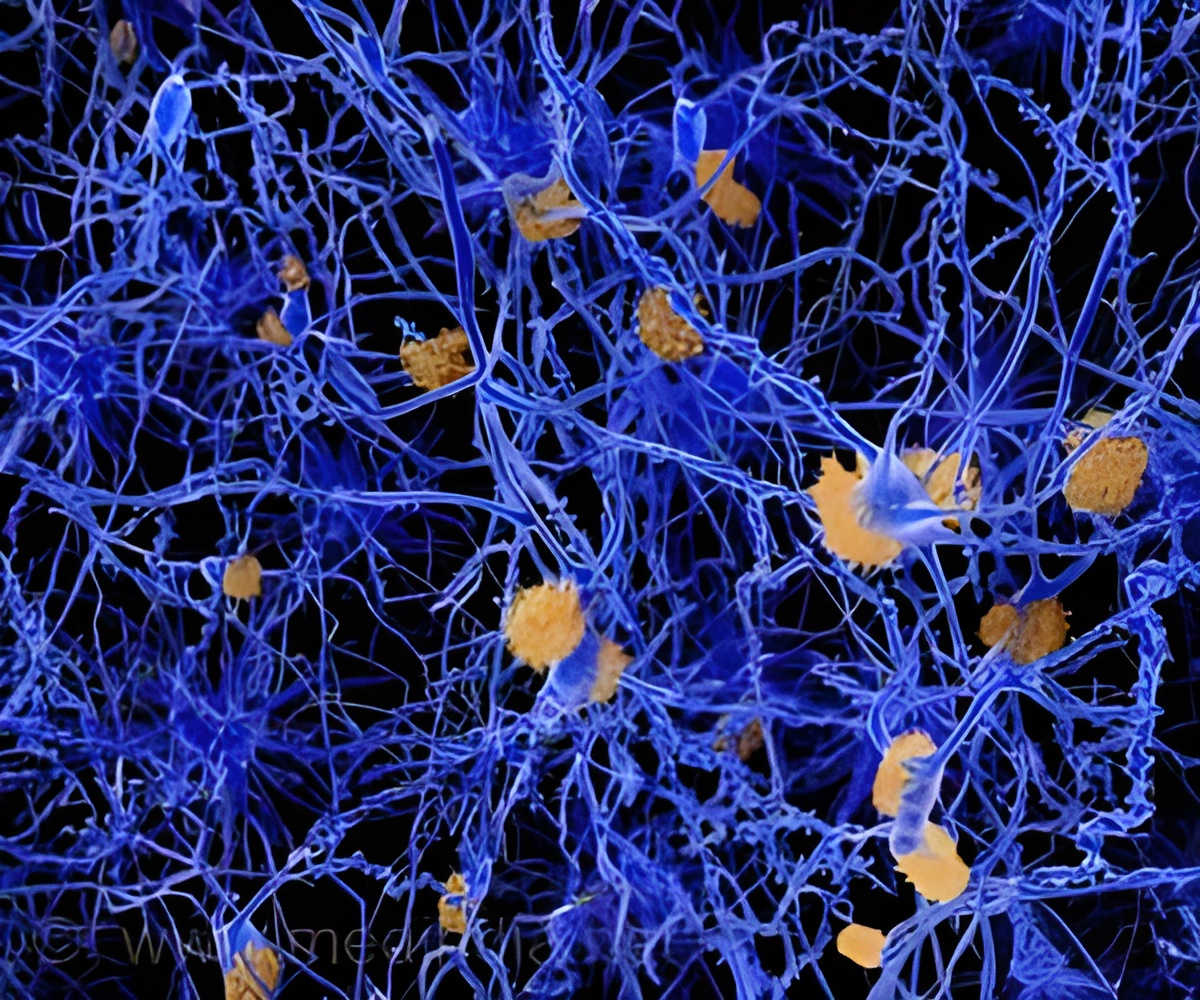

The model for memory consolidation claims that the hippocampus forms new memories and, as time goes on, trains the cortex to store enduring memories.

‘The brain area hippocampus involved in memory consolidation in mice, and which is associated with human patients with memory disorders-provide an inroad for further research and analysis. ’

"We wanted to watch how a memory changes in the same mouse, in the same neurons, over time," says Andrew C. Toader, an MD/PhD student in Rajasethupathy's lab and co-author of the study. "So we had to develop technology to observe neurons in intervening areas between the hippocampus and cortex over weeks, tracking them and seeing how they change."

Learning, Recalling, and Thinking - Discovering the Brain

Armed with this new technology, Rajasethupathy and her team began investigating how memories consolidate in mice. Since the mice would need to stay relatively still for weeks of imaging, the team had the mice run in place on an axially rotating styrofoam ball, akin to a treadmill, while viewing virtual reality mazes. The mice received very high rewards for making certain turns in the maze, while their other navigational decisions resulted in minor positive or negative feedback. One month later, the mice were still scampering solely toward those areas in the maze that had resulted in the high rewards, a clear indication that they only remembered decisions that had resulted in high payoffs."The key was that the mice could learn all three outcomes in the short-term—very high rewarding, low rewarding, and adverse—but only the high reward would be remembered a month out, because it was the most salient memory," says Josue Regalado, a PhD student in Rajasethupathy's lab and co-author of the study. "That way, we could measure the differences in the neural circuit when recording memories that will be conserved."

The team found that the brain's anterior thalamus appears to referee memory-consolidating interactions between the hippocampus and the cortex. While Rajasethupathy found this surprising—"the anterior thalamus hasn't been a prominent part of memory consolidation models"—the finding also made some sense. She knew that humans with Korsakoff Syndrome suffer severe amnesia and memory loss, and happen to have lesions on the anterior thalamus.

Further investigation confirmed that the thalamus plays a key role in memory consolidation in mice. In two subsequent experiments, Rajasethupathy's team found that inhibiting the thalamus disrupts the formation of long-term memories in mice and, conversely, boosting the thalamus takes memories that would not have otherwise been stored long-term, and makes them last.

"There are a lot of ways to make memories not happen," Regalado says. "One of the major breakthroughs of this paper is that we show that manipulating the anterior thalamus is one way to increase the importance of a memory, and make the mice store it long-term."

Advertisement

Even then, the thalamus is likely only part of a developing story. "We don't think the thalamus is the only region needed for memory consolidation, and we hope our findings will be blended with other models out there describing this intervening region," she says.

Advertisement