The feasibility of large-scale, standardized protein measurements, which are necessary for validation of disease biomarkers and drug targets was demonstrated by an international team of scientists.

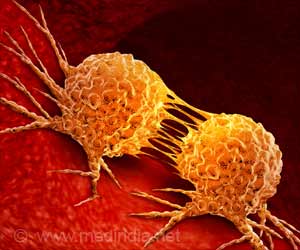

"Having a global resource for standardized quantification of all human proteins would set new standards that would undoubtedly increase the reproducibility of preclinical research, which would have a dramatic impact on the translation of novel therapeutics and diagnostics." Proteins, the molecular workhorses of all biological functions, hold the key to signaling early disease and disease progression. Cancer biomarkers are especially sought after – the protein fingerprints in cells could lead to tests to detect the disease earlier, to identify a person's specific risk of cancer long before it develops, and to better guide patients' treatments. But validating newly discovered biomarker candidates has proven impossible without standardized and reproducible methods to measure their levels, Paulovich said. Each promising biomarker must be further studied in clinical trials, which requires researchers to measure the abundance of each candidate biomarker in hundreds to thousands of patient samples. Because the odds are extraordinarily low that any one candidate will translate to clinical use, large numbers of proteins must be tested to identify a clinically useful biomarker.

"Right now, you can't make robust measurements of most human proteins," Paulovich said. "More than 10 years after the human genome has been sequenced and we have the full catalog of molecules as important as proteins, we still can't study the human proteome with any kind of throughput in a standardized, quantitative manner." To address this problem, Paulovich and her colleagues used a sensitive and targeted protein-measurement technology called multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry, or MRM-MS. This type of mass spectrometry is not new – it has been used for years in clinical laboratories worldwide to measure drug metabolites and small molecules associated with inborn errors of metabolism. More recently, Paulovich and others have begun using it to measure human proteins. The researchers' method enables highly specific, precise, multiplex (meaning the technique measures several different proteins in a single experimental assay) quantification of a minimum of 170 proteins in 20 clinical samples per instrument per day; no other existing technology has this power. Because the mass spectrometry technique is targeted, meaning the researchers can tune the instruments to look for a specific subset of proteins in cancer cells or other sample types, it can detect the presence of proteins of interest at much lower levels in tiny blood samples or biopsies than a non-targeted tactic.

"The goal is to position this technology to displace some very old technologies that are currently being used," said Jacob Kennedy, an analytical chemist in Paulovich's group and lead author of the study. Currently, researchers usually use either Western blotting, ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), or immunohistochemistry (IHC) techniques to measure levels of proteins in clinical samples. These methods are often not reproducible from laboratory to laboratory, rendering validation of candidate biomarkers for clinical use very difficult, and they cannot be used for large numbers of proteins and samples at once. Paulovich and her colleagues assayed more than 300 proteins known to be produced by breast cancer cells to validate their technique; their results showed that MRM-MS could recapitulate and extend observations made in previous studies of breast cancer using other technologies.

The study, which included collaborating research groups from the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Mass., and the Seoul National University and Korea Institute of Science and Technology, South Korea, demonstrated MRM-MS's capacity to measure many proteins at once in a standardized way, laying the foundation for an international, organized effort to quantitate every protein in the human proteome. Their study – the largest to demonstrate the technique's reproducibility across laboratories and the only international study to do so – has pushed the capacity of the technology the farthest, measuring hundreds of protein pieces where others have measured dozens."We really showed what could happen if governments cooperated to build a community resource," she said.

"It's doable, it's scalable, and the resource is useful." Paulovich's team hopes the technique catches on in research communities around the world. To facilitate this, her group is spearheading the development of an open-source website to create a centralized resource of highly validated assays for the research community. The portal, funded by the Clinical Proteomics Tumor Analysis Consortium Initiative (CPTAC) of the National Cancer Institute, is set to launch in early 2014.

Advertisement