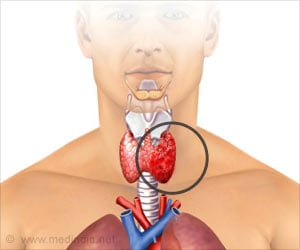

Cancer cachexia causes loss of appetite, weight loss and wasting in most patients with cancer towards the end of their lives.

‘The inability to generate energy sources by the liver triggers a hormonal response that suppresses the immune cell reaction to cancers, and causes failure of anti-cancer immunotherapies.’

The condition known as cancer cachexia, causes loss of appetite, weight loss and wasting in most patients with cancer towards the end of their lives. However, cachexia often starts to affect patients with certain cancers, such as pancreatic cancer, much earlier in the course of their disease. In research published in the journal Cell Metabolism, the scientists have shown in mice that even at the early stages of cancer development, before cachexia is apparent, a protein released by the cancer changes the way the body, in particular the liver, processes its own nutrient stores.

"The consequences of this alteration are revealed at times of reduced food intake, where this messaging protein renders the liver incapable of generating sources of energy that the rest of the body can use," explains Thomas Flint, an MB/PhD student from the University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine and co-first author of the study.

"This inability to generate energy sources triggers a second messaging process in the body - a hormonal response -- that suppresses the immune cell reaction to cancers, and causes failure of anti-cancer immunotherapies."

"Cancer immunotherapy might completely transform how we treat cancer in the future -- if we can make it work for more patients," says Dr Tobias Janowitz, Medical Oncologist and Academic Lecturer at the Department of Oncology at the University of Cambridge and co-first author.

Advertisement

The next step for the team is to see how this discovery might be translated for the benefit of patients with cancer. "If the phenomenon that we've described helps us to divide patients into likely responders and non-responders to immunotherapy, then we can use those findings in early stage clinical trials to get better information on the use of new immunotherapies," says Professor Duncan Jodrell, director of the Early Phase Trials Team at the Cambridge Cancer Centre and co-author of the study.

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert