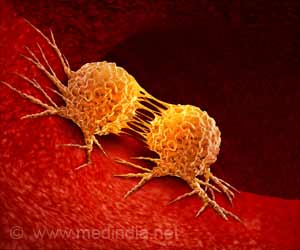

ETH scientists have discovered new cancer-specific molecular changes that could potentially inform the development of cancer treatments.

‘In majority of the cancer types tested, alternative splicing occurred much more frequently in tumor tissues than in healthy tissues.’

Now the ETH researchers have gone a step further and taken a closer look at the RNA molecules, which are responsible for transcribing the cell's DNA. But before these molecules can serve as a blueprint for the biosynthesis of proteins, they undergo a series of transformative cellular processes: in a process called splicing, specialised enzymes cut out entire sections from the RNA molecule and join the sequences on either side together. An RNA molecule can be spliced in a range of different ways, which experts refer to as "alternative splicing". In other words, as a copy of a gene an RNA molecule can deliver the blueprint for various protein forms, the groundwork for which is laid during splicing. Alternative splicing happens frequently

In their analysis for tumor-specific alternative splicing, Rätsch and his colleagues looked at an unprecedented volume of genetic cancer data, examining sequences in RNA molecules from 8,700 cancer patients. They found several ten thousand previously undescribed variants of alternative splicing that crop up over and over in many cancer patients.

It is especially pronounced in pulmonary adenocarcinomas, where alternative splicing occurs 30 percent more frequently than in healthy samples.

Thanks to this study, the researchers gained new insights into which molecular factors cause the high rate of alternative splicing in cancer cells. Some genetic mutations that encourage alternative splicing are already known, but now the team was able to identify another four genes involved.

Advertisement

"Cancer leads to molecular and functional changes in cells. You could say that in cancer cells, there's lots of sand in the gears," says André Kahles, a postdoc in Rätsch's group and one of the study's two lead authors. "At the molecular level the changes come not only in the form of individual DNA mutations, which we've known about for a long time, but also to a great extent in the form of different kinds of RNA splicing, as we were able to show in our comprehensive analysis."

Advertisement

In targeted cancer immunotherapy, the body's own immune system is trained to recognise typical molecular cancer markers so it can attack and kill cancer tissue. Healthy body tissue is left alone.

At present only a minority of cancer patients can be treated with this method, since tumor-specific markers suitable for use in immunotherapy were present in only some 30 percent of cases. The newly discovered variations of alternative splicing lead to changes in proteins that in turn can also serve as tumor-specific markers: up to 75 percent of cases were found to exhibit these new markers that could potentially be used for developing specific medications.

In-depth analysis of larger datasets

Simply obtaining information on the frequency of alternative splicing is in itself highly valuable. Specifically, the scientists theorise that tumor tissue with many splicing operations is particularly vulnerable to another type of immunotherapy, namely non-targeted immunotherapy. They wish to explore this hypothesis as part of the ETH Domain's Personalized Health and Related Technologies (PHRT) research programme.

For the study described here, the researchers analysed several hundred terabytes of raw data. "To analyse such huge volumes of data, we needed an enormous amount of computer time and fast storage systems. Without a supercomputer, the study would not have been possible," ETH Professor Rätsch says. He and his colleagues came to ETH Zurich two years ago from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, where they had started the study. Once in Switzerland, they joined forces with ETH's IT Services to set up the Leonhard Med computer system, which let them securely process gigantic sets of genomic and other medical data.

Source-Eurekalert