Challenges associated with dengue versions or serotypes such as that how an Infection by one serotype typically results in long-term protection specific to that serotype, but a later exposure to a different serotype can result in more severe disease are being studied in this study.

‘As dengue as four versions or serotypes, infection by one serotype typically results in long-term protection specific to that serotype. However, a later exposure to a different serotype can result in more severe disease. This is the challenge they are trying to overcome in this study.’

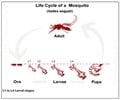

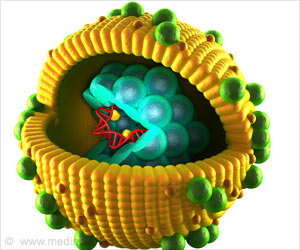

Like Zika, yellow fever and West Nile viruses, dengue belongs to a group of mosquito-borne viruses that circulate in many tropical countries. However, without effective treatment and a safe licensed vaccine, dengue infection can lead to debilitating illnesses, including severe pain and hemorrhagic fever. One of the challenges of dengue infection is that it can be caused by one of four versions - or serotypes - of the virus, which are numbered dengue 1 to 4. Infection by one serotype typically results in long-term protection specific to that serotype. However, a later exposure to a different serotype can result in more severe disease. Experts believe this phenomenon occurs due to a part of the immune response, the antibodies, which may recognize and promote the second infection rather than defeat it.

"Trying to tease out the protective immune response in naturally infected patients is a challenge, since people living in high-risk areas likely have been exposed to multiple serotypes of the virus, which confound the observation," said senior study author Sean Diehl, Ph.D., an assistant professor of microbiology and molecular genetics at the University of Vermont's (UVM) Vaccine Testing Center and Center for Translational Global Infectious Disease Research. "In our model, we controlled the infection for safety reasons, and the participants were monitored for six months in order to understand the biological changes that occur following the infection."

Over six months, Diehl and his colleagues tracked the immune response and measured its different aspects, from the levels of certain immune blood cells to the levels of antibodies they produce and how these antibodies can recognize different dengue serotypes. In this study, co-led by Huy Tu, a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate in UVM's Cellular and Molecular Biomedical Sciences program, the group defined the evolution of the antibody response in dengue infection in a controlled human model where subjects were treated with a weakened version of the virus.

The research showed that the study participants developed an antibody response against the virus as early as two weeks after the infection. This immune response was highly focused against the infecting serotype, neutralized the virus, and persisted for months afterward. With a comprehensive approach, the study dissected the antibody response at the single-cell level resolution, mapped the interaction between human antibodies to structural components on the virus's surface, and connected the functional features of the response during an acute infection to time points past recovery.

Advertisement