A group of researchers has discovered that a class of chemotherapy drugs originally designed to inhibit key signaling pathways in cancer cells also kills the parasite that causes malaria.

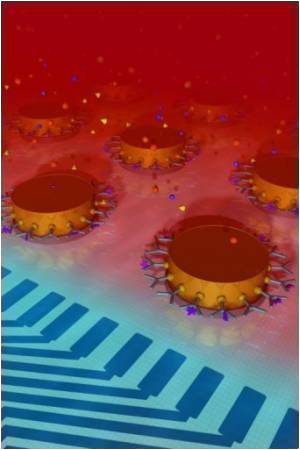

The research shows that the malaria parasite depends upon a signaling pathway present in the host - initially in liver cells, and then in red blood cells - in order to proliferate. The enzymes active in the signaling pathway are not encoded by the parasite, but rather hijacked by the parasite to serve its own purposes.

These same pathways are targeted by a new class of molecules developed for cancer chemotherapy known as kinase inhibitors. When the GHI/Inserm team treated red blood cells infected with malaria with the chemotherapy drug, the parasite was stopped in its tracks.

Professor Christian Doerig and his colleagues tested red blood cells infected with Plasmodium falciparum parasites and showed that the specific PAK-MEK signaling pathway was more highly activated in infected cells than in uninfected cells. When they disabled the pathway pharmacologically, the parasite was unable to proliferate and died. Applied in vitro, the chemotherapy drug also killed a rodent version of malaria (P. berghei), in both liver cells and red blood cells.

This indicates that hijacking the host cell's signaling pathway is a generalized strategy used by malaria, and thus disabling that pathway would likely be an effective strategy in combating the many strains of the parasite known to infect humans.

The research has been published online in the journal Cellular Microbiology.

Advertisement