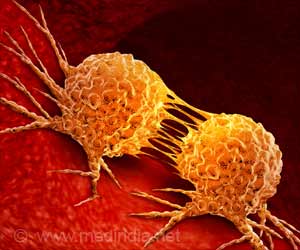

A University of Michigan study has found that the absence or low function of a gene, called CHFR in breast cells trigger abnormal cells which are predisposed to become cancerous.

A University of Michigan study has found that the absence or low function of a gene, called CHFR in breast cells trigger abnormal cells which are predisposed to become cancerous.

The study lays the foundation for better ways to choose most effective breast cancer treatments, and analysis of CHFR gene is also a hot area of interest among researchers trying to explain colorectal, stomach, lung and other forms of cancer.The findings have revealed how and why new "daughter" cells, produced as cells in body tissues renew themselves, receive too few or too many chromosomes if expression of the CHFR gene is missing or low. The loss of CHFR can lead to the survival of genetically unstable cells loaded with too many chromosomes, which can lead to cancer.

"Our findings show that loss of CHFR disrupts normal chromosome segregation in breast cells during cell division and creates genomic instability, which can drive genetic mechanisms that accelerate the development of cancer," said Elizabeth Petty, M.D. , a U-M professor in the departments of human genetics and internal medicine and the senior author of the study.

The findings can shed more light on the scientific basis for diagnostic markers and identify which patients can benefit from specific types of cancer drugs.

"Our previous findings, and the work of others, have shown that cancer cells cultured in the lab that have low or absent CHFR expression are more susceptible to treatment with a class of drugs called taxanes, such as paclitaxel (Taxol) and docetaxel, that attack the dividing cells when they are trying to separate their chromosomes," said Lisa Privette, Ph.D., the study's first author, a recent U-M Medical School graduate and now a researcher at Cincinnati Children's Hospital.

She added: "These drugs are frequently used to treat breast cancer and other types of cancer and they work by targeting the structure used to separate chromosomes. Our work provides further evidence for this correlation and begins to explain how the expression of CHFR alters the cell's response to these kinds of drugs."

Advertisement

"It's likely that some other mechanism is shutting down CHFR. Currently, we are actively looking at ways in which CHFR may be turned off in normal cells, in hopes that we can find a molecular switch to keep it turned on and decrease the risk of cancer development," she said.

Advertisement

In the new study, the researchers report what happens inside a dividing cell nucleus when CHFR is missing. For this, the researchers studied normal and cancerous human breast tissue samples in cell culture to find out how CHFR affects certain proteins. They focused on proteins that regulate how spindles form and how chromosomes divide and form along the spindle.

They then found that CHFR interacts with alpha tubulin, a protein important in forming mitotic spindles, and with a key mitotic spindle checkpoint regulator, MAD2, previously implicated in breast cancer. They found that when CHFR is absent, MAD2 does not do its job.

"Cells without CHFR not only have problems creating the structure or apparatus necessary to separate the chromosomes between the two daughter cells during cell division. They also have an impaired ability to detect and correct the problem before the chromosomes separate. Prior to our findings, we knew that breast cancer cells often had the wrong number of chromosomes, but no one had identified any gene, or group of genes, that could account for the high frequency of this problem," said Privette.

She said that the new study, "provides one reason why the majority of breast cancer cells have too many chromosomes, which is a major hallmark of malignant cancers. Although a lot of work remains, and other genes are likely involved, our work on the role of CHFR in breast cancer development is an interesting and important piece of a very large puzzle."

The study appeared online ahead of print in the journal Neoplasia.

Source-ANI

KAR