A new discovery by scientists has ensured that vaccine against Chlamydia, a common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in humans, may not be far away.

A new discovery by scientists has ensured that vaccine against Chlamydia, a common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in humans, may not be far away.

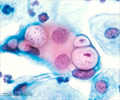

A thesis from the Sahlgrenska Academy has shown that when a woman becomes infected with Chlamydia, the first white blood cells that arrive at the scene to fight the infection are not the most effective.The disease is caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis, which is transmitted by unprotected sexual contact. Many don't realise that they have been infected, because Chlamydia infection often has no symptoms at all. Without effective antibiotic treatment the infection can become chronic and may even lead to infertility.

"Now that we know how the body defends itself against the Chlamydia bacteria, we can develop a vaccine that optimises that defence. We have a basic understanding of how the vaccine could work, but some work remains to be done. We believe that it will take a few years before the vaccine becomes a reality," says researcher Ellen Marks, the author of the thesis.

The body defends itself against infections with a type of white cell called the T lymphocyte. When these blood cells take on the bacteria, they trigger an inflammation that can damage tissue, so there are also other similar blood cells whose main task is to reduce the inflammation and protect tissue.

Marks and her colleagues discovered that these anti-inflammatory forces predominate in the lower parts of the female genital tract, mainly mediated by a hormone called IL-10, which is highly protective against tissue damage.

"The result is that the T lymphocytes that could fight Chlamydia are not concentrated in the lower vagina, and the infection can move up towards the womb and fallopian tubes relatively unhindered," Marks said.

Advertisement

"The method of administration is an important remaining issue. Previous research has shown that injections don't work, and so the vaccine will probably need to be given either as a nasal spray or in the form of a cream applied into the vagina," Marks said.

Advertisement

RAS