Johns Hopkins experts on the genetics of a potentially lethal heart rhythm defect that runs in families and targets young athletes report they have greatly narrowed the hunt for the genetic mutations…

Johns Hopkins experts on the genetics of a potentially lethal heart rhythm defect that runs in families and targets young athletes report they have greatly narrowed the hunt for the specific genetic mutations that contribute to the problem.

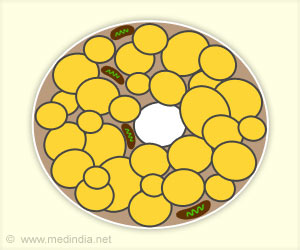

Their new findings, described in the July issue of the American Journal of Human Genetics, should increase the accuracy of tests to identify those at risk for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), which is among the top causes of sudden cardiac death in the young and fit.In February, the same team linked one-third of ARVD cases in their large database of patients to a dozen abnormal changes in a gene called plakophilin-2 (PKP2), which makes proteins involved in heart cell stickiness.

In the new study, confirming experiments elsewhere, the Hopkins team found four mutations in another sticky protein gene, Desmoglein-2 (DSG2), in five of 33 patients tested.

“This gene is highly expressed in the heart, where muscle tissue expands and contracts with the heartbeat,” says senior study author and cardiac geneticist Daniel P. Judge, M.D. “Our results confirm that altered genes in the desmosomal cellular complex are responsible for ARVD. And now that we know the genetic roots of this disease, we can also create better blood tests for their proteins to predict who is at risk for developing this condition.”

ARVD is characterized by weakness in the desmosome, or cell-to-cell binding structure. The inherited condition leads to the buildup of excess fatty and scar tissue in the heart’s right ventricle, causing irregular beats and - unless diagnosed and treated with drugs or implanted defibrillators - triggering a fatal heart rhythm disturbance.

Judge, an assistant professor at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and its Heart Institute, says DSG2 mutations appear to account for at least 10 percent and possibly more of the estimated 25,000 deaths each year from ARVD.

Advertisement

More than 400 people have been screened at Hopkins so far and of these, two-thirds have had serious enough forms of the condition to warrant implantation of a defibrillator, an electrical device that corrects any disturbances in the heart's rhythm.

Advertisement

When scientists excluded their ARVD patients with PKP2 mutations, they were left with 33 who had no known genetic explanation for their condition. Additional testing revealed the four mutations in DSG2.

'We knew right away that we had found something very significant,' says lead author Mark Awad, B.A., a medical and predoctoral sciences student at Hopkins. 'The mutations were confined to a highly functional part of the gene and were highly conserved, meaning that evolution had not drastically changed the genetic sequence over time - the gene was kept the way it was because it was important to the heart’s normal function.'

According to Awad, not everyone with a genetic mutation develops ARVD. He adds that further analysis of the condition’s genetic roots will help researchers to calculate the precise increased risk from each mutation for developing symptoms and dying. Previous research by the Hopkins team showed that familial ARVD generally strikes after puberty and its symptoms - dizziness, fatigue and fainting after exercise - may appear up to 15 years before diagnosis.

Source-Newswise

SRM