Blacks and other minorities were less likely to receive colonoscopy from more highly-rated physicians, finds a study.

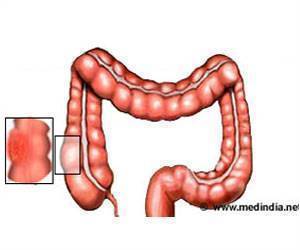

‘Most colorectal cancers begin as a growth called a polyp on the inner lining of the colon or rectum, but not all polyps become cancer.’

The study, appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine, finds that blacks and other minorities were less likely to receive colonoscopy from more highly-rated physicians, though variations in quality of screening did not account for the black-white differences in interval cancers. Screening for colorectal cancer is effective in reducing incidence and mortality by detecting precancerous lesions or cancer at more curable stages. But colorectal cancers can still develop in screened populations. Some are missed at the time of screening; others can develop between recommended screenings. Interval colorectal cancers, defined as cancers that develop after a negative result on colonoscopy but before the next recommended test, account for 3% to 8% of colorectal cancer cases in the United States.

Studies have identified some of the factors that could increase the risk of interval colorectal cancer, including patient demographics, clinical factors, and physician factors, including quality of colonoscopy metrics. However, patterns of risk for interval colorectal cancer by race/ethnicity are not well known. The risk for blacks was of interest to authors because colorectal incidence and mortality rates in blacks are the highest among any race or ethnicity in the United States.

To further investigate, investigators led by Stacey Fedewa, Ph.D. looked for interval colorectal cancer occurrence among 61,0000 patients ages 66 to 75 in the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program who had received a colonoscopy between 2002 and 2011. There were 2,735 interval colorectal cancers identified during that time. Physicians' polyp detection rate was used a surrogate measure of quality of colonoscopy, with higher detection rates representing better quality.

The probability of interval colorectal cancer by the end of follow-up was 7.1% in blacks and 5.8% in whites. Blacks were more likely than whites (52.8% versus 46.2%) to have received colonoscopy from physicians with a lower polyp detection rate, and polyp detection rate was significantly associated with the risk of an interval cancer.

Advertisement

"Blacks and other minorities more frequently received colonoscopies from physicians with lower polyp detection rates, suggesting there was lower quality of care," said Dr. Fedewa. "Our findings are consistent with previous reports that blacks were more likely to receive healthcare from physicians in lower resource settings and also experienced poorer outcomes. We also observed greater black-white differences among patients receiving colonoscopies from physicians with higher but not lower polyp detection rates, which aligns with previous observations that disparities in outcomes and healthcare utilization often manifest when higher quality medical interventions and care become available . In other words, interventions that improve outcomes for patients can, somewhat ironically, increase disparities, since they're often less available to ethnic minorities."

Advertisement