New targets for human proteins that can control the spread of HIV have been predicted using a novel computational analysis, finds study published in PLoS Computational Biology.

David Badger of Blacksburg, Va., one of Murali's graduate students, and Matthew D. Dyer of Applied Biosystems of Foster City, Cal., also contributed to the study, which was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health to Katze, the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute Fellows Program to Murali and Tyler, and the Virginia Tech's Support Program for Innovative Research Strategies to Murali.

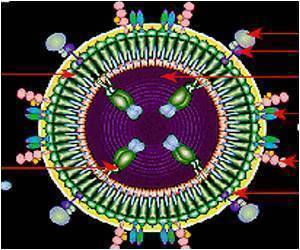

When a person contracts HIV, it causes the progressive failure of the body's immune system, with the onset of life threatening infections and diseases such as cancer. Over 25 years of intensive research have failed to create a vaccine for preventing HIV. Moreover, drugs used to cure HIV become rapidly ineffective because HIV is able to develop mutations against drugs, Murali said.

A recent line of research is examining whether human proteins can be targeted to cure HIV. Since viruses such as HIV have very small genomes, they must exploit the cellular machinery of the host to spread. Therefore, disrupting the activity of selected host proteins may impede viruses. Moreover, since human proteins evolve at a much slower rate than HIV proteins, human proteins that are targeted by drugs are very unlikely to develop mutations that render the drugs ineffective.

In fact, three studies published in 2008 systematically silenced virtually every human gene in order to discover HIV Dependency Factors (HDFs), i.e., those genes that are necessary for HIV to survive and replicate. Each of these three studies discovered hundreds of HDFs. However, a puzzling aspect was that only a handful of HDFs were common to two or more experiments.

Advertisement