It is well known that humans enjoy a symbiotic relationship with the good microbes that colonize their bodies.

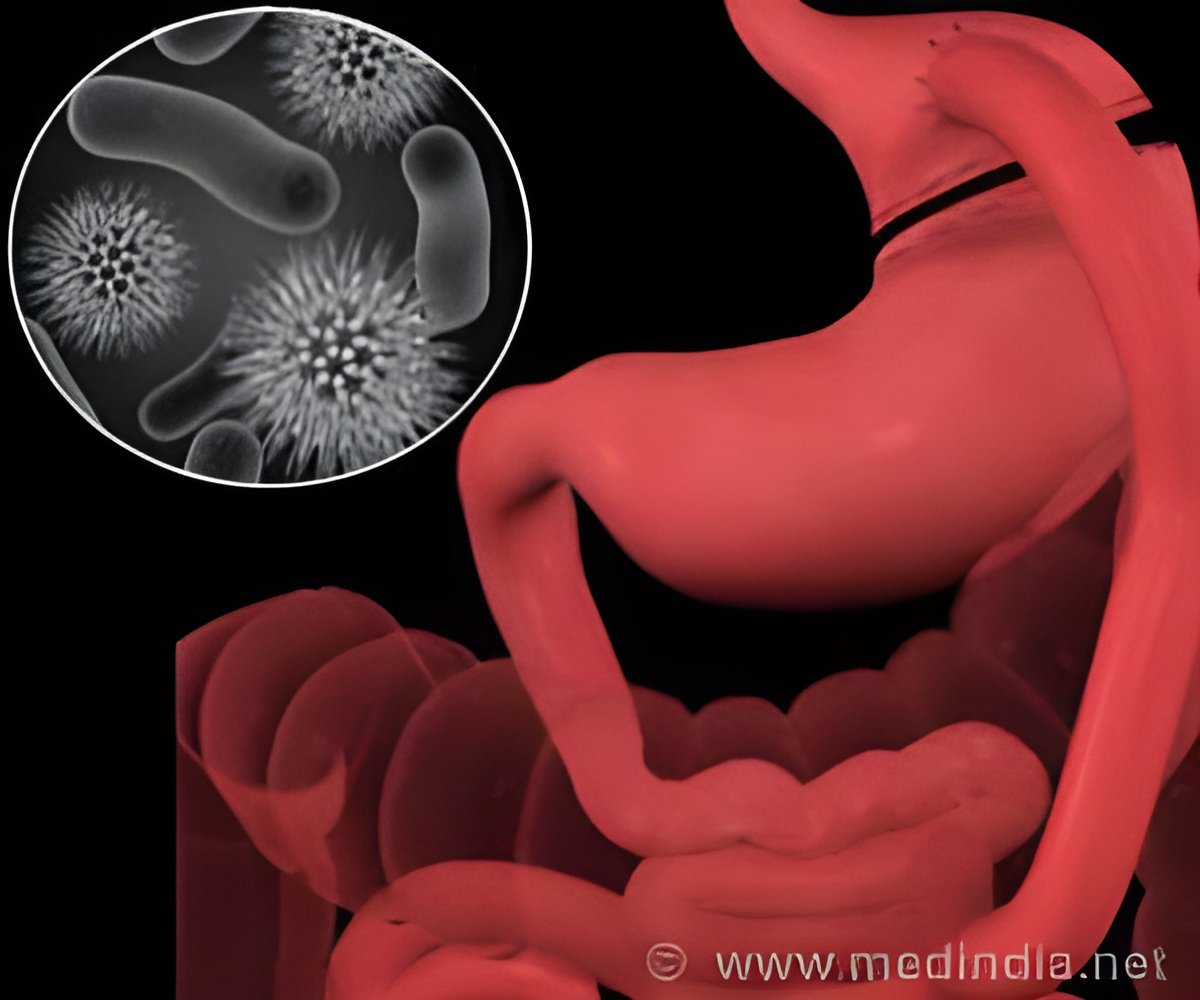

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is one of the best-studied diseases associated with alterations in the composition of beneficial bacterial populations. However, the nature of that relationship, and how it is maintained, has yet to be clarified.

Now, researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have identified a molecule that appears to play a starring role in this process.

David Artis PhD, associate professor of Microbiology, and colleagues report in Nature that the enzyme HDAC3 is a key mediator in maintaining proper intestinal integrity and function in the presence of friendly bacteria. What's more, HDAC3 and the genetic pathways it controls appears critical to maintaining a healthy balance between intestinal microbes and their host.

"HDAC3 in intestinal epithelial cells regulates the relationship between commensal bacteria and mammalian intestine physiology," says first author Theresa Alenghat VMD PhD, instructor in the Department of Microbiology.

That humans rely on their microbial cohabitants is hardly news. Much normal human physiology is attributable to our relationship to our microbiota.

Advertisement

The team focused their efforts on HDAC3, which belongs to a family of enzymes that can be responsive to environmental signals. And HDAC3 itself, an enzyme that modifies DNA and turns down gene expression, had previously been identified to have various inflammatory and metabolic roles.

The team then developed a mouse model that would mimic that observation. They created transgenic mice that lacked HDAC3 specifically in the intestinal epithelium and found that these animals exhibited altered gene expression in their intestinal epithelial cells.

The mice also showed signs of altered intestinal health. They lacked certain cells, called Paneth cells, that produce antimicrobial peptides. The mouse intestines seemed to be more porous than normal, and they showed signs of chronic intestinal inflammation, exhibiting some of the symptoms observed in patients with IBD.

When the team examined the diversity of the microbial population colonizing the mutant animal intestines, they found they were different from normal animals, with some species being overrepresented in HDAC3-deficient mice. "There's a fundamental change in the relationship between commensal bacteria and their mammalian hosts following deletion of HDAC3 in the intestine," Artis explains.

But, if the mutant animals were grown in the absence of bacteria, their intestinal symptoms largely disappeared, as did many of the observed differences in gene expression. In other words, HDAC3 was influencing the bacterial population, and the bacteria in turn were influencing the cells' behavior.

The implication, Artis says, "is that intestinal expression of HDAC3 is an essential component of how mammals regulate the relationship between commensal bacteria and normal, healthy intestinal function."

These findings, says Alenghat, suggest a role for HDAC3 in human disease, but the exact nature of that link is still being worked out. Whether dysregulation of the enzyme, or the genetic programs it oversees, actually contributes to human IBD is a question the team is currently investigating.

"Obviously more has to be done, but it is clear that this is a pathway that is of significant interest as we continue to define how mammals have co-evolved with beneficial microbes," says Artis.

Other Penn-based authors are Lisa C. Osborne, Steven A. Saenz, Dmytro Kobuley, Carly G. K. Ziegler, Shannon E. Mullican, Inchan Choi, Stephanie Grunberg, Rohini Sinha, Meghan Wynosky-Dolfi, Annelise Snyder, Paul R. Giacomin, Karen L. Joyce, Tram B. Hoang, Meenakshi Bewtra, Igor E. Brodsky, Gregory F. Sonnenberg, Frederic D. Bushman, Kyoung-Jae Won, and Mitchell A. Lazar.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (AI061570, AI095608, AI087990, AI074878, AI095466, AI106697, AI102942, AI097333), the Crohns and Colitis Foundation of America, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the Cancer Research Institute.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $4.3 billion enterprise.

The Perelman School of Medicine has been ranked among the top five medical schools in the United States for the past 16 years, according to U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools. The School is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $398 million awarded in the 2012 fiscal year.

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's patient care facilities include: The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania -- recognized as one of the nation's top "Honor Roll" hospitals by U.S. News & World Report; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center; Chester County Hospital; Penn Wissahickon Hospice; and Pennsylvania Hospital -- the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751. Additional affiliated inpatient care facilities and services throughout the Philadelphia region include Chestnut Hill Hospital and Good Shepherd Penn Partners, a partnership between Good Shepherd Rehabilitation Network and Penn Medicine.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2012, Penn Medicine provided $827 million to benefit our community.

Source-Newswise