Scientists in protective coveralls wage war against a fingernail-sized danger behind air-tight doors in a lab in a southern French city.

First spotted in Albania in 1979, the black-and-white striped invader has gained a foothold on Europe's Mediterranean rim and is advancing north and west, according to captors' reports.

Colonies are established in 20 European countries, in moderate climes as far north as Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands.

"The risk of disease is very low but it is growing," entomologist Jean-Baptiste Ferre told AFP at France's leading mosquito-control institute.

"The more mosquitoes there are, the higher the risk."

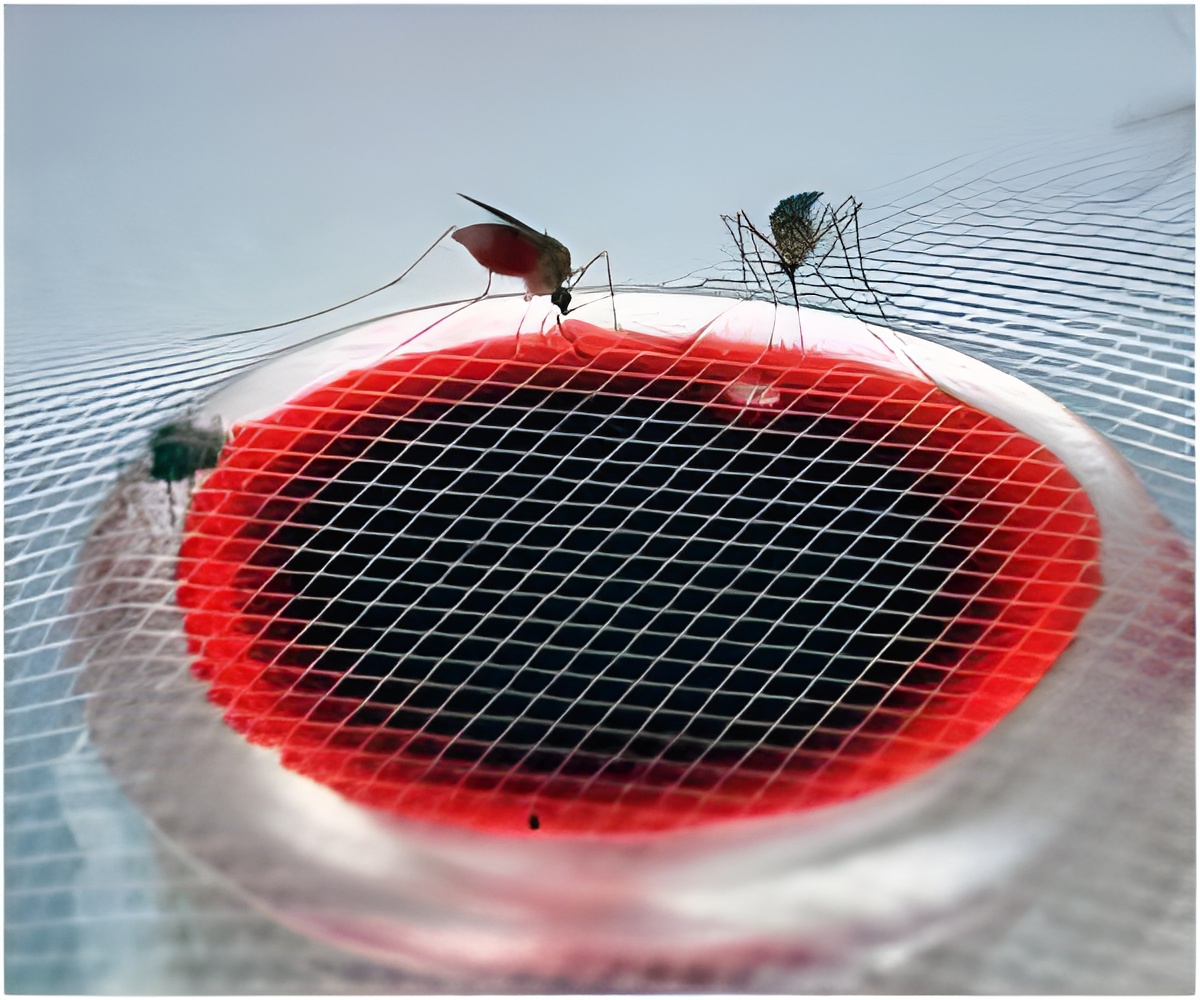

The Asian tiger mosquito -- Latin name Aedes albopictus -- can spread many kinds of viruses.

Advertisement

A. albopictus transmits the virus by taking blood from a sick person and handing on the pathogen the next time it takes a meal.

Advertisement

In 2007, the tiger mosquito caused a home-grown outbreak in Italy of chikungunya, and in 2010, 10 locally-transmitted cases of dengue occurred in Croatia.

That same year, two cases of each disease surfaced in southern France, prompting the alarm bells to ring loudly.

From Montpellier, Ferre and his colleagues at the Entente Interdepartementale pour la Demoustication en Mediterranee (EID) monitor the spread with some 1,500 traps dotted around France, luring mosquitoes to lay their eggs.

These provide insights into how A. albopictus is adapting to European life, with its varied habitats and cooler climate.

Ferre points to maps that begin in 2004, when a tiny red dot represented the first settling of albopictus in France around Menton, near the Italian border.

Year by year, the dot grows into red tentacles that probe north and west.

The insect has a flight range of only about 200 metres (yards), so it hitch-hikes a ride in cars, trucks and traded goods.

With climate change, "further expansion is probable," the journal Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases warned this year.

That assessment is supported by scientists at Britain's University of Liverpool who point to warming trends in the Balkans and northwestern Europe.

Asian tiger mosquitoes are aggressive and robust, able to breed prolifically in their short, 10-day lives.

Feeding during the day, they can bite several people in quick succession, and their offspring can hatch even after long periods without water.

Worse, the insect is a stealthy urban dweller.

It does not need large, open bodies of water to reproduce, for it can lay its eggs in small, water-holding receptacles such as flowerpots, toys and blocked gutters, and this makes it much harder to fight.

Since May this year, surveillance in France has thrown up 267 suspected dengue and chikungunya cases among people who had arrived from abroad, said EID project coordinator Gregory Lambert.

The institute sometimes launches pre-emptive strikes if this can prevent the mosquitoes from spreading disease locally.

It orders out insecticide trucks that spray streets in a 200-metre (650-foot) radius around the area where a case is notified.

The operations take place before dawn, while most people are still in bed.

"The imperative is to kill the mosquitoes before they transmit the disease," said Lambert.

The war is unrelenting.

"It is impossible to kill them all," said Anna-Bella Failloux of France's Pasteur Institute, one of the world's top centres for infectious disease.

"Even if there is no mosquito around you, you still have eggs somewhere, waiting for the next rain."

Source-AFP