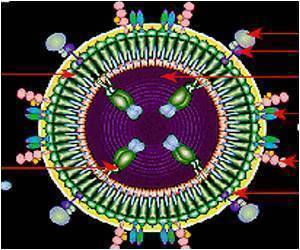

For the first time, researchers have described that the 4-million-atom structure of the HIV's capsid, or protein shell.

Scientists have long struggled to decipher how the HIV capsid shell is chemically put together, said senior author Peijun Zhang, Ph.D., associate professor, Department of Structural Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

"The capsid is critically important for HIV replication, so knowing its structure in detail could lead us to new drugs that can treat or prevent the infection," she said.

"This approach has the potential to be a powerful alternative to our current HIV therapies, which work by targeting certain enzymes, but drug resistance is an enormous challenge due to the virus' high mutation rate," she added.

Previous research has shown that the cone-shaped shell is composed of identical capsid proteins linked together in a complex lattice of about 200 hexamers and 12 pentamers, Dr. Zhang said.

But the shell is non-uniform and asymmetrical; uncertainty remained about the exact number of proteins involved and how the hexagons of six protein subunits and pentagons of five subunits are joined. Standard structural biology methods to decipher the molecular architecture were insufficient because they rely on averaged data, collected on samples of pieces of the highly variable capsid to identify how these pieces tend to go together.

Advertisement

Collaborators at the University of Illinois then used their new Blue Waters supercomputer to run simulations at the petascale, involving 1 quadrillion operations per second, that positioned 1,300 proteins into a whole that reflected the capsid's known physical and structural characteristics.

Advertisement

"The capsid is very sensitive to mutation, so if we can disrupt those interfaces, we could interfere with capsid function," Dr. Zhang said.

"The capsid has to remain intact to protect the HIV genome and get it into the human cell, but once inside it has to come apart to release its content so that the virus can replicate. Developing drugs that cause capsid dysfunction by preventing its assembly or disassembly might stop the virus from reproducing," she noted.

The findings were highlighted on the cover of the May 30 issue of Nature.

Source-ANI