Signaling a potential new approach to treat diabetes, researchers have produced insulin-secreting cells from stem cells derived from patients with type 1 diabetes.

‘Signaling a potential new approach to treat diabetes, researchers have produced insulin-secreting cells from stem cells derived from patients with type 1 diabetes.’

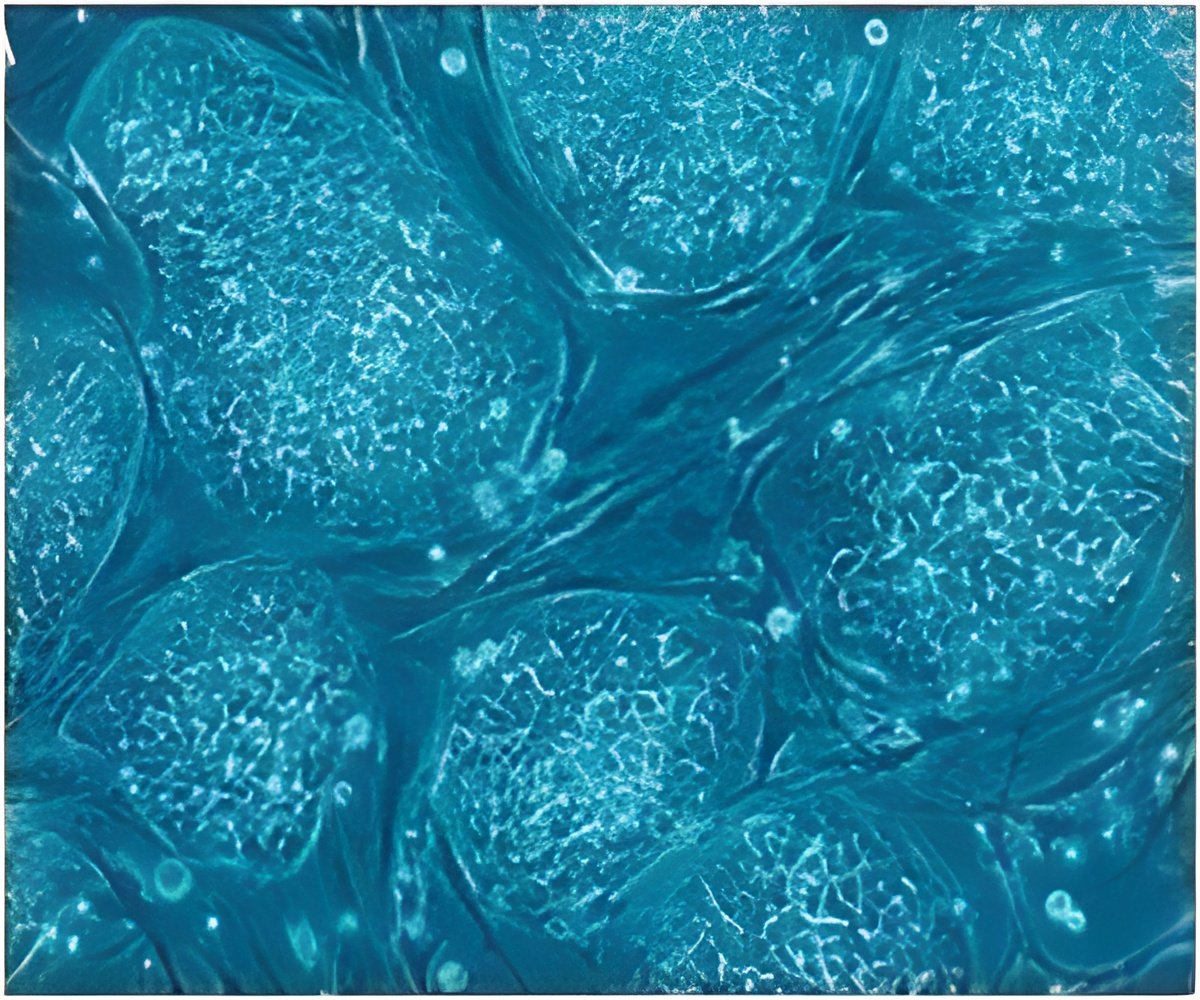

"In theory, if we could replace the damaged cells in these individuals with new pancreatic beta cells -- whose primary function is to store and release insulin to control blood glucose -- patients with type 1 diabetes wouldn't need insulin shots anymore," said first author Jeffrey R. Millman, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine and of biomedical engineering at Washington University School of Medicine. "The cells we've manufactured sense the presence of glucose and secrete insulin in response. And beta cells do a much better job controlling blood sugar than diabetic patients can." Millman, whose laboratory is in the Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Lipid Research, began his research while working in the laboratory of Douglas A. Melton, PhD, Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and a co-director of Harvard's Stem Cell Institute. There, Millman had used similar techniques to make beta cells from stem cells derived from people who did not have diabetes. In these new experiments, the beta cells came from tissue taken from the skin of diabetes patients.

"There had been questions about whether we could make these cells from people with type 1 diabetes," Millman explained. "Some scientists thought that because the tissue would be coming from diabetes patients, there might be defects to prevent us from helping the stem cells differentiate into beta cells. It turns out that's not the case."

Millman said more research is needed to make sure that the beta cells made from patient-derived stem cells don't cause tumors to develop -- a problem that has surfaced in some stem cell research -- but there has been no evidence of tumors in the mouse studies, even up to a year after the cells were implanted.

He said the stem cell-derived beta cells could be ready for human research in three to five years. At that time, Millman expects the cells would be implanted under the skin of diabetes patients in a minimally invasive surgical procedure that would allow the beta cells access to a patient's blood supply. "What we're envisioning is an outpatient procedure in which some sort of device filled with the cells would be placed just beneath the skin," he said.

Advertisement

Millman said that the new technique also could be used in other ways. Since these experiments have proven it's possible to make beta cells from the tissue of patients with type 1 diabetes, it's likely the technique also would work in patients with other forms of the disease -- including type 2 diabetes, neonatal diabetes and Wolfram syndrome. Then it would be possible to test the effects of diabetes drugs on the beta cells of patients with various forms of the disease.

Advertisement