Scientists found that digestive health can be enhanced with quickly evolving bacteria.

"In some regards, this is one of the best demonstrations of evolution ever carried out in a laboratory," said William Parker, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Duke Department of Surgery. "This is the first time the evolution of bacteria has been monitored for a period of years in an incredibly complex environment."

Parker said the work illustrates the power of evolution in creating diversity and in filling ecological niches. "This study also strengthens the idea that we could harness evolution in the laboratory to develop microbes for use in biotechnology and in medicine," Parker said.

The results, which appear in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology, indicate that "experimental evolution," or evolution controlled in a laboratory setting, could be used to develop new strains of bacteria for use as probiotic substances, which are living organisms used for intestinal and digestive therapies.

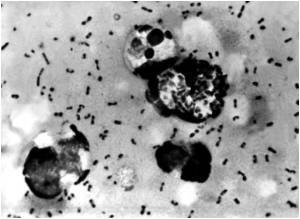

The scientists put a single strain of bacteria, brushed onto the mice, in a colony of otherwise bacteria-free mice. The study bacteria were engineered to make a structure (called a type 1 pilus) that helps them stick to things. The researchers hoped to learn how the molecule would affect the interaction between the bacteria and the mice.

"We were surprised, because we thought we would be able to study this engineered bacterium for a while, but we were wrong," Parker said. The bacteria started to mutate and quickly lost the pilus structure that had been engineered into them. The single homogeneous strain was rapidly evolving into a diverse community of organisms.

Advertisement

Over the three-year study period, the bacterial population remained diverse and appeared to adapt significantly well to the environment in the digestive tracts of the mice. "The bacteria colonized better in the mice by the end of the experiment than at the beginning," Parker said, with more than a three-fold increase in the density of bacteria within the gut by the end of the experiment.

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert

SAV