Human brain resembles a flock of birds. It comes to a consensus about which way to fly based on closeness and formation the birds are to one another.

This study is the first to provide a mechanistic explanation for how the frontal cortex accomplishes this feat, exerting control over trillions of individual neurons. The work weds cutting-edge neuroscience with the emerging field of network science, which is often used to study social systems.

It applies control theory, a field traditionally used to study electrical and mechanical systems, to show that being on the "outskirts" of the brain is necessary for the frontal cortex to dynamically control the direction of thoughts and goal-directed behavior.

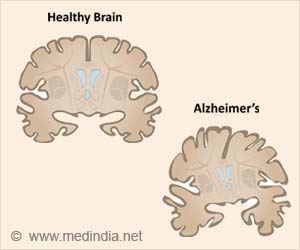

This fundamental understanding of how the brain controls its activity could help lead to better interventions for medical conditions associated with reduced cognitive control, such as autism, schizophrenia or dementia.

Senior author Danielle Bassett said that the results suggest that the human brain resembles a flock of birds. The flock comes to a consensus about which way to fly based on how close the birds are to one another and in what formation.

Birds that fly at specific places in the flock can drive changes in the flock's direction, being leaders in a so-called multi-agent system. Similarly, particular regions of your brain are predisposed to control your thoughts based on where they lie in relation to other regions. The study is published in Nature Communications.

Advertisement