Doctors urge a ban on popular kitchen worktops to prevent incurable lung disease caused by silica dust exposure during manufacturing and installation.

Artificial stone silicosis: a UK case series

Go to source). Made from crushed rocks bound together with resins and pigments, artificial stone, also known as engineered or reconstituted stone, or ‘quartz’, has surged in popularity over the past 20 years, particularly for use in kitchen worktops, they explain.

‘Artificial stone worktops could be killing you! New cases of silicosis, a deadly lung disease, linked to its manufacture & installation. Time for a ban? #artificialstone #silicosis #healthrisk’

It has aesthetic appeal. It’s easier to work with due to the absence of natural imperfections, and it’s more resistant to damage than natural stone, they add. Artificial Stone and the Silicosis Crisis

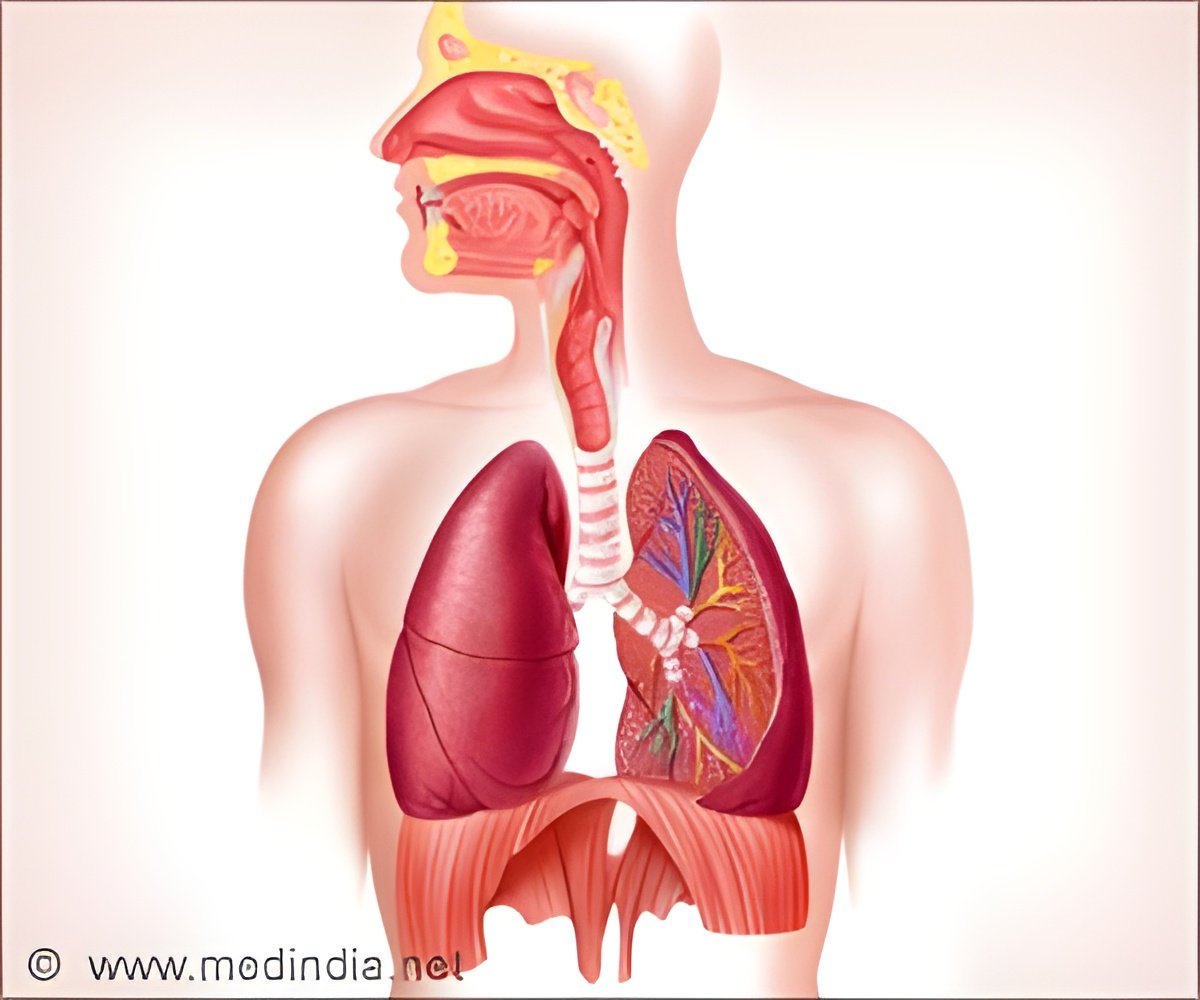

But its increasing popularity has been accompanied by the emergence of a severe and rapidly progressive form of silicosis (artificial stone silicosis), largely driven by its high (more than 90%) silica content compared with marble (3%) and granite (30%), and the fine dust it generates when cut.When worktops are prepared for installation, they are also often ‘dry’ cut and polished with an angle grinder or other hand tools without the use of water to suppress dust generation, further boosting the volume of fine dust, explain the authors.

Cases of artificial stone silicosis have been reported from Israel, Spain, Italy, the USA, China, Australia and Belgium since 2010. But while artificial stone has been used in the UK for a similar period, no cases had been reported until mid-2023, when 8 men were referred to a specialist occupational lung disease clinic.

Their average age was 34, but ranged from 27 to 56 at the time of diagnosis. Six were born outside the UK and seven smoked or used to smoke.

Advertisement

Two were assessed for lung transplant; 3 were assessed for autoimmune disease. Two were treated for opportunistic lung infection caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria.

Advertisement

They all reported that this was done without consistent water suppression, and without what they felt was appropriate respiratory protection. And even where workshop ventilation was present, the men stated that the system had not been serviced or cleaned regularly. None of them was aware of active airborne dust monitoring in the workplace.

Against medical advice, three continue to work with artificial stone, and have subsequently reported reduced exposure to visible dust after the introduction of powered respirators and water suppression. Two are no longer working; one has continued to work, but is no longer exposed to the dust; one has died; and one has been lost to further check-ups.

“Onset of disease is likely to relate to exposure levels, suggesting levels, at least for some of the UK cases were extremely high and implying that employers failed to control dust exposure and to adhere to health and safety regulations,” point out the authors.

“The [artificial stone] market is dominated by small companies in which regulation has been shown to be challenging to implement. Furthermore, at least some worktop manufacturers may fail to provide adequate technical information relating to potential risks,” they add.

“Even with cessation of exposure, disease progression has been noted in over 50% of cases over [an average] of 4 years. Prevention of disease is therefore critical,” they emphasise.

While the number of workers exposed to silica dust isn’t known, global experience indicates that cases are likely to increase significantly in the coming years, they point out.

Current UK guidance recommends monitoring workers in the industry after 15 years, but that is very likely to miss cases and fails to account for intensity, not just length, of exposure, they suggest.

“A concerted effort is required in the UK to prevent the epidemic seen in other countries. The cases we present illustrate the failure of the employer to take responsibility for exposure control in their workplaces. National guidelines are urgently needed, as well as work to enumerate the at-risk population and identify cases early,” they insist.

“The introduction of a legal requirement to report cases of [artificial stone] silicosis, implementation of health and safety regulation with a focus on small companies, and a UK ban on artificial stone (as introduced in Australia in 2024) must be considered,” they urge.

In a linked editorial, Dr Christopher Barber, of Sheffield Teaching Hospitals says that history is instructive, citing the observations of Dr Calvert Holland in 1843 on the health of Sheffield cutlery workers.

These workers shaped metal forks using a rotating grindstone and developed incurable ‘grinders asthma’ as a result of the very high levels of dust generated by ‘dry grinding’ forks (without water).

Barber comments: “By design, [artificial stone] worktops (like grindstones) have a very high silica content to make them more hard wearing and durable. Dry processing of [it] with powered tools without the use of water suppression, local exhaust ventilation, and respiratory protective equipment exposes workers to very high levels of airborne silica dust, in many cases two orders of magnitude greater than legal exposure limits.”

Holland noted the vulnerability of the cutlery workers, and Barber draws parallels with those working with artificial stone.

“Many of those at risk of [artificial stone] silicosis in the UK, Australia, and USA are migrant workers whose first language is not English, who may have poor understanding of health risks, and limited access to healthcare,” he writes.

And they are more likely to have limited financial options, forcing some to continue harmful exposures against medical advice, he adds.

“Considering the availability of [artificial stone] kitchen worktops, the arrival of [artificial stone] silicosis in the UK is one which has been feared by clinicians for some time,” he says.

But UK doctors may struggle to differentiate the signs and symptoms from sarcoidosis, a condition that is unrelated to silica inhalation, but which has similar clinical features, he suggests.

“Greater awareness of [artificial stone] silicosis is also required among a wider range of healthcare professionals due to the increased risk of mycobacterial, renal, and autoimmune connective [tissue] disease,” he says.

The UK is currently reviewing exposure limits for crystalline silica dust amid mounting international concerns about its health impacts.

A New Study on Silica Exposure Levels

To inform the current debate about permissible levels of exposure, researchers in a separate study reviewed for the first time the available evidence published up to the end of February 2023 to establish cumulative risk and identify the exposure level at which that risk would be reduced.They searched for studies drawing on x-rays, post mortem examination results, and death certificates for silicosis, spanning an average period of more than 20 years since participants’ first employment in the stone cutting industry.

Eight studies out of an initial haul of 52 met the eligibility criteria, involving 8792 cases of silicosis among 65,977 participants. Six of the studies involved miners.

The cumulative risk estimates varied substantially, depending on which methodological approach had been used, so the researchers pooled the raw data to recalculate the lifetime cumulative risk and the level at which the absolute risk of developing the disease would be reduced.

The results showed that among miners halving cumulative exposure from 4 mg/m³ (equivalent to 40 years of work at 0.1 mg/m³ or 420 cases/1000 workers) to 2 mg/m³ (equivalent to 40 years of work at 0.05 mg/m³ intensity) of breathable silica dust corresponded to a substantial reduction in risk of 77%, resulting in 323 fewer cases/1000 workers.

The equivalent figures for those working in other industries were a reduction in risk of 45% and 23 fewer cases per 1000 workers down from 51. But, importantly, these figures are based on only 2 studies, highlight the researchers.

“There is current debate regarding respirable crystalline silica exposure limits in the UK and recent debate among miners in the USA. This research supports the reduction of permissible exposure limits from 0.1 mg/m³ to 0.05 mg/m³" over an 8-hour working shift, conclude the researchers.

Reference:

- Artificial stone silicosis: a UK case series - (https://thorax.bmj.com/content/early/2024/07/04/thorax-2024-221715)

Source-Eurekalert