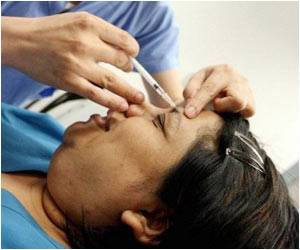

The effect of manganese, a trace metal that is naturally present in the human body, on the nervous system has been tracked down.

Manganese, a metal that is naturally present in the human body, may contribute to Parkinson's disease when defective genes interact to enhance its toxicity, according to a study published Sunday.

Parkinson's attacks the nervous system and is characterized by the loss of cells which produce dopamine, a critically important neurotransmitter that ferries chemical messages within the brain.Symptoms include muscular rigidity, difficulty with initiating movements, lack of balance, and slowness of voluntary actions.

In experiments on yeast cells, researchers showed that the toxicity caused by an over-abundance of a protein, alpha-synuclein, previously linked to the disease is greatly reduced in the presence of a second protein, known as ATP13A2.

The latter is thought to play a role in transporting metal molecules, especially manganese, a known risk factor for Parkinson's.

Manganese is an essential trace nutrient in virtually all forms of life. The human body contains about 10 milligrammes, stored mainly in the liver and kidneys.

A team led by Susan Lindquist at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts demonstrated that yeast cells lacking ATP13A2 were more sensitive to the metal.

Advertisement

Their findings, published in Nature Genetics, a publication of the Nature Publishing Group, suggest that humans with mutations in the genes encoding these proteins may be particularly vulnerable to manganese poisoning.

Advertisement

Manganese exposure is regulated by the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Meanwhile, in another study published in Nature Genetics, researchers identified the first genetic variant ever linked to the condition known as essential tremor.

Like Parkinson's, essential tremor is a degenerative neurological disease characterised by tremor of the arms and hands that can impair writing, drinking, eating and other everyday activities.

Earlier studies suggested that the condition may occur in as many as 13 percent of persons over 65.

Researchers led by Kari Stefansson of deCODE Genetics, a company based in Reykjavik, Iceland, compared the genomes of 452 essential tremor patients from Iceland against a control group of 14,394 persons.

They found that a specific variant in the gene known as LINGO1 was strongly linked to the disease.

LINGO1 is involved in cell-to-cell interactions within the nervous system, and is known to regulate neuron survival.

Inhibiting the gene's activity has been shown to improve neurological function in test animals, and could be a promising path for new drug treatments.

Source-AFP

PRI/SK