Group A Steptocococcus (GAS) can survive and multiply in endothelial cells, but epithelial cells remove GAS infection via xenophagy.

‘After having a viral infection, the length of time a patient is infectious for depends on the type of virus involved. The infectious period often begins before the patient starts to feel unwell or notice a rash.’

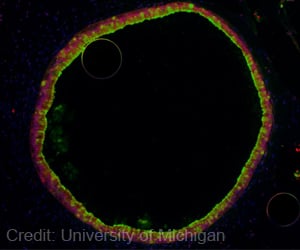

Most infections enter the body through organs that are in constant contact with the outside environment, such as the lungs and intestines. Accordingly, the epithelial cells lining these organs have developed an immune system that removes the infection by using intracellular machinery known as xenophagy. Professor Tamotsu Yoshimori, Osaka University, explained, "Xenophagy is a type of autophagy that acts on foreign invasions. Autophagy is a method through which a cell destroys unneeded or defective material." Yoshimori therefore wondered if endothelial cells lining blood vessels are as equipped with xenophagy machinery as epithelial cells. In a new published study, his team of researchers discovered that they are not. "We found that Group A Steptocococcus (GAS) can survive and multiply in endothelial cells, but epithelial cells remove GAS infection via xenophagy. The reason for the difference is insufficient ubiquitination of the invading GAS," he shared.

Ubiquitination is a common process used by autophagy that marks the cellular material to be disposed. These markings result in a membrane structure that forms around the material, a structure that was absent around GAS in endothelial cells but present around GAS in epithelial cells. "If we coated the GAS with ubiquitin before infecting the cell, we found xenophagy worked in endothelial cells comparably to epithelial cells," noted Dr. Tsuyoshi Kawabata, a member of the lab who managed the project. Adding, "If ubiquitin could activate xenophagy, then we know that the cell has all the equipment it needs.

The challenge is to identify what molecular targets can activate the system. This information could be used for drug discovery." The group searched for chemicals that regulate this signaling pathway, finding that the chemical 8-nitro-cGMP was expressed at much lower levels in endothelial cells than epithelial cells. Indeed, inhibiting this molecule allowed GAS to thrive in epithelial cells, but had no effect on GAS survival in endothelial cells. However, despite these promising results, Kawabata worries nitric oxide regulators are not practical drug targets.

"The problem with nitric oxide is that it is a vasodilator. There is an evolutionary reason that the vascular system does not produce too much nitric oxide because it risks severely low blood pressure," shared Kawabata. Instead, Kawabata believed that attention should be given to other molecular pathways that regulate the ubiquitination. While the study pointed to nitric oxide signaling, it also found evidence that nitric-oxide independent factors could regulate the recruitment of ubiquitin to execute xenophagy on GAS.

Advertisement

Source-ANI