Experts say that the brawl on Mount Everest last weekend stems from the tension between elite climbers and growing commercial expeditions.

While there are many views on who was to blame, all agree the spark was a decision by the Europeans to climb the Lhotse Face, a steep ice wall, while the Nepalese guides were rigging up ropes for their commercial clients.

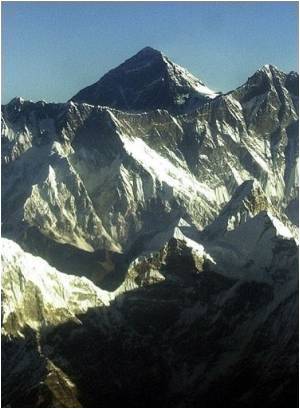

Last year, hundreds of commercial climbers were famously photographed as they queued to reach the summit, illustrating the huge number of people who flock to the 8,848-metre (29,029 ft) peak each year.

Expecting similar crowds this season, the Expedition Operators' Association of Nepal recommended before the start of the 2013 summit season that Sherpas be sent to fix two sets of ropes -- one for ascent and one for descent.

"This year the tensions occurred while the Sherpas were beginning to implement that plan," Mohan Krishna Sapkota, a spokesman in the Tourism Ministry, told AFP.

Moro, Steck and Griffith say they did not interfere with the rope-rigging and they deny as "highly unlikely" allegations that they dislodged ice that hit the rope-fixing Sherpa team.

Advertisement

"I know that on the day the ropes are fixed, nobody should hang on the fixed ropes," Moro told National Geographic. "This doesn't mean that nobody is allowed to climb the mountain."

Advertisement

Freddie Wilkinson, a US mountaineer and Everest veteran, told AFP that the disagreement highlighted rising friction caused by the competing interests of elite climbers and commercial adventurers.

"Elite climbers think ropes detract from the sport. On the other side are the commercial climbing operators who say it's their right to do business," he said in an interview.

"But the assertion that the route is closed to all climbers while the Sherpas fix the ropes shows a seismic shift in mountaineering etiquette. It means the climbing companies are determining the rules now," he said.

Witnesses say the parties exchanged blows for approximately 20 minutes.

While the details of the drama remain murky, the increased crowding on the peak has raised questions about the safety -- and meaning -- of expeditions.

"Something like this has been coming for a long time," said Sumit Joshi, owner of Himalayan Ascents, who saw the brawl take place.

"For anyone on the mountain, it's obvious who is working the hardest. It's the Sherpas doing so much work and they never get any recognition," he said.

Everest is no stranger to controversy and as technology and ambitions have advanced, crowding on the mountain has increased.

The stage was set for this year's disagreement in some ways by German mountaineer Ralf Dujmovits' photograph depicting a queue of hundreds of summit hopefuls ascending at once during the 2012 climbing season.

In an interview last week with Outside Magazine, Dujmovits said the image may have had the opposite effect of his intent: "People may start thinking, 'if there are so many people, I can also queue up.'"

Wilkinson told AFP the recent brawl exposed "the socioeconomic reality of what it means to climb Everest", calling the tension a "symptom of the fundamental Everest conundrum" over commercial climbing.

Last Monday all parties signed a peace accord at base camp. But the trio has cancelled their trip and won't say whether they will ever attempt the world's highest peak again.

Moro said the incident killed his "climbing spirit", and promises of safe passage from Nepalese authorities did not outweigh the trust the men had lost in Everest and the Sherpas.

The tourism ministry in Kathmandu says the government will launch a formal investigation into the incident.

But Wilkinson believes any probe will yield few results.

"The common bond among these disparate groups on the mountain may indeed be that they all have a vested interest in sweeping this under the rug so they can continue climbing and working," he said.

Source-AFP