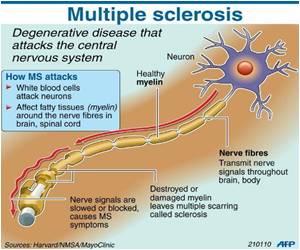

Researchers said that an experimental therapy has shown promise in treating multiple sclerosis without weakening the immune system and could help target other autoimmune and allergic diseases.

Current treatments for the disease inhibit the immune system in an effort to prevent the resulting symptoms, like paralysis and blindness.

That places patients at risk of infection and other serious illnesses like cancer.

The phase 1 clinical trial of nine patients in Germany used their white blood cells to stealthily deliver billions of myelin antigens into their bodies.

The aim was to get their immune systems to recognize myelin as harmless and develop a tolerance to the material.

It was able to reduce the immune system's reactivity to myelin by 50 to 75 percent.

Advertisement

"The therapy stops autoimmune responses that are already activated and prevents the activation of new autoimmune cells."

Advertisement

Miller, who has been working on the problem for more than 30 years, had previously shown that the treatment stopped the progression of relapsing-remitting MS in mice.

"In the phase 2 trial, we want to treat patients as early as possible in the disease before they have paralysis due to myelin damage." Miller said. "Once the myelin is destroyed, it's hard to repair that."

The primary aim of the phase 1 study was to demonstrate the treatment's safety.

It found no adverse effects from the intravenous injection of up to three billion white blood cells with myelin antigens.

Most importantly, it did not reactivate the patients' disease and did not affect their immunity to real pathogens.

Miller has shown in previous non-clinical studies that the therapy was also effective at treating type 1 diabetes, asthma and peanut allergy.

It can be adapted to other autoimmune and allergic diseases by switching the antigens attached to the white blood cells.

Attaching the antigens to white blood cells is a costly and labor-intensive process. So Miller also tested using nanoparticles to deliver the antigen and found it was an effective alternative in mice.

The study was published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

It resulted from a collaboration between Northwestern's Feinberg School, University Hospital Zurich in Switzerland and University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany.

Source-AFP