Just 48 hours of fasting was enough to protect mice from the side effects of an intensive chemotherapy treatment which wiped out much of the cancer in their bodies, according to a

Just 48 hours of fasting was enough to protect mice from the side effects of an intensive chemotherapy treatment which wiped out much of the cancer in their bodies, according to a study published Monday.

Should the same results be found in humans, it could protect cancer patients from the ravages of chemotherapy drugs and also potentially allow for significantly more aggressive treatment."We were able to treat with a very high dose of chemo and the animals were running around like we didn't give them anything," said lead author Valter Longo, an Italian researcher at the University of Southern California.

"Everyone was really focusing on how to kill cancer cells. Instead, we said lets leave that alone and kill the cancer cells the same way but protect everything else much better."

Longo's team has already applied for approval to run a small clinical trial on cancer patients in California.

They are also looking at ways to get the same protective effects without actually fasting by administering either a drug or a highly specific diet.

"We're exploiting the ability of every organism that's ever been tested to go into this starvation response mode which is usually associated, counterintuitively, with the high resistance to almost anything you throw at them," he said in a telephone interview.

Advertisement

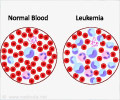

Longo and his team tested the starvation response to chemotherapy drugs in yeast, human and rat cells and then mice injected with a highly aggressive form of cancer which affects children.

Advertisement

The starved yeast were able to withstand up to 1,000 times more stress and toxicity.

The starved human and rat cells had a tenfold increase in resistance to chemotherapy while cancer cells received no protection and, in some cases, were weakened by the starvation.

The starved mice showed "no visible sign of stress or pain" after chemo treatments which were either three or five times the comparatively maximum dose allowed in humans, according to the study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

While they lost 20 percent of their body weight in two days of fasting, the mice regained most of the weight in the four days following chemotherapy. Those starved for 60 hours lost 40 percent of their weight but regained it within a week.

More than half of the mice which were not starved before treatment died of toxicity and those which survived lost 20 percent of their body weight following treatment. Only one of the 28 starved mice died.

The single chemotherapy treatment was not sufficient to wipe out all of the cancer that had been injected into the mice.

However, it did double the life expectancy of the starved mice which lived up to 60 days after being injected with an aggressive cancer which usually kills mice in less than 30 days.

Longo's team is currently working on another study to see if multiple chemotherapy treatments can totally cure the starved mice of their cancer.

"Ideally, you want to kill all the cancer cells, but if you think about it, it might not even be necessary to get to that level," he said.

"You can't necessarily expect to kill all the cancer cells based on the cancer, but this could allow you to keep it under control - if it works - by doing many, many different cycles of chemo."

The simplicity of the treatment will help it reach patients quickly should it prove to be safe and effective.

"We should have pretty solid results just a few weeks after we start the study," Longo said, explaining that standard blood tests can show whether or not patients were protected by fasting.

"Within a year, you could have this into many different hospitals, if it works, and that's a big if," he said.

The initial trial will not risk increasing chemotherapy doses but simply test for the protective value of a brief period of starvation. It will take more testing to see if starvation can be used to safely increase the doses and frequency of chemo treatments.

"Eventually this is going to work," he told AFP.

"We just have to find the equivalent... is it 48 hours, or is it 48 hours plus maybe targeting certain receptors in certain genes? We know the system pretty well we just have to find the equivalent. I'm confident that within a year or two we'll have that."

Source-AFP

SRM/L