Neuroscientists at Johns Hopkins have uncovered the mystery behind pain sensitivity and its fluctuations, by identifying a gene that regulates a heat-activated molecular sensor.

A gene that regulates a heat-activated molecular sensor may explain why people have different degrees of pain sensitivity, neuroscientists at Johns Hopkins have revealed.

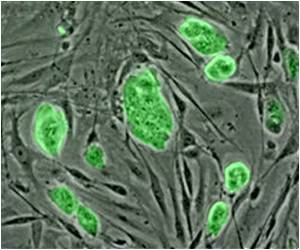

The scientists have described the function of this membrane protein, called Pirt, in regulating pain sensitivity, specifically why it's variable instead of being constant."Pain sensitivity increases during inflammation or injury and we want to know what molecules are involved in pain sensation when sensitivity is elevated," said Xinzhong Dong, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neuroscience at Hopkins.

It is the TRPV1 protein channel found on the surface of certain nerve cells that controls the ability to sense temperature heat and spice. While inactive, TRPV1 channels remain closed and there is no pain sensation.

But, when noxious heat-temperatures above 108 degrees Fahrenheit or capsaicin, the main ingredient in "hot" peppers, activates a TRPV1 channel, ions flow through, depolarizing the nerve to create an electrical current that sends pain signals to the brain.

"The interesting thing about this channel is it's not always constant," said Dong.

His team wanted to find proteins that modulate TRPV1's action and discovered the Pirt protein, phosphoinositide interacting regulator of TRP, and named it for its ability to regulate the TRPV1 channel.

Advertisement

Later, they exposed one hind paw to capsaicin and found that mice lacking Pirt did not lick their paws as long as normal mice, indicating that without Pirt, they were compromised in their ability to sense the spice of capsaicin. They also found that Pirt's action is specific to capsaicin and not other chemicals.

Subsequent research revealed that Pirt interacts with one more molecule in the cell, a so-called acidic phospholipid, allowing access to TRPV1. Dong said that through this phospholipid Pirt somehow changes the TRP channel, perhaps by opening it wider, or maybe by causing it to stay open longer, which causes elevated pain sensitivity. However, the exact mechanism of how Pirt regulates the TRPV1 channel is still not clear.

"The goal is to find molecules that specifically affect the pain pathway, but not other nerves. We're looking for genes specifically turned on in pain-sensing neurons. If we find them and can target them with new drugs, we will be able to treat pain without unfavorable side effects," he said.

The study recently appeared in the May 2 issue of Cell.

Source-ANI

RAS/L