Stem cell gene therapy is used to be used to target a life-threatening immunodeficiency in newborns called SCID-X1.

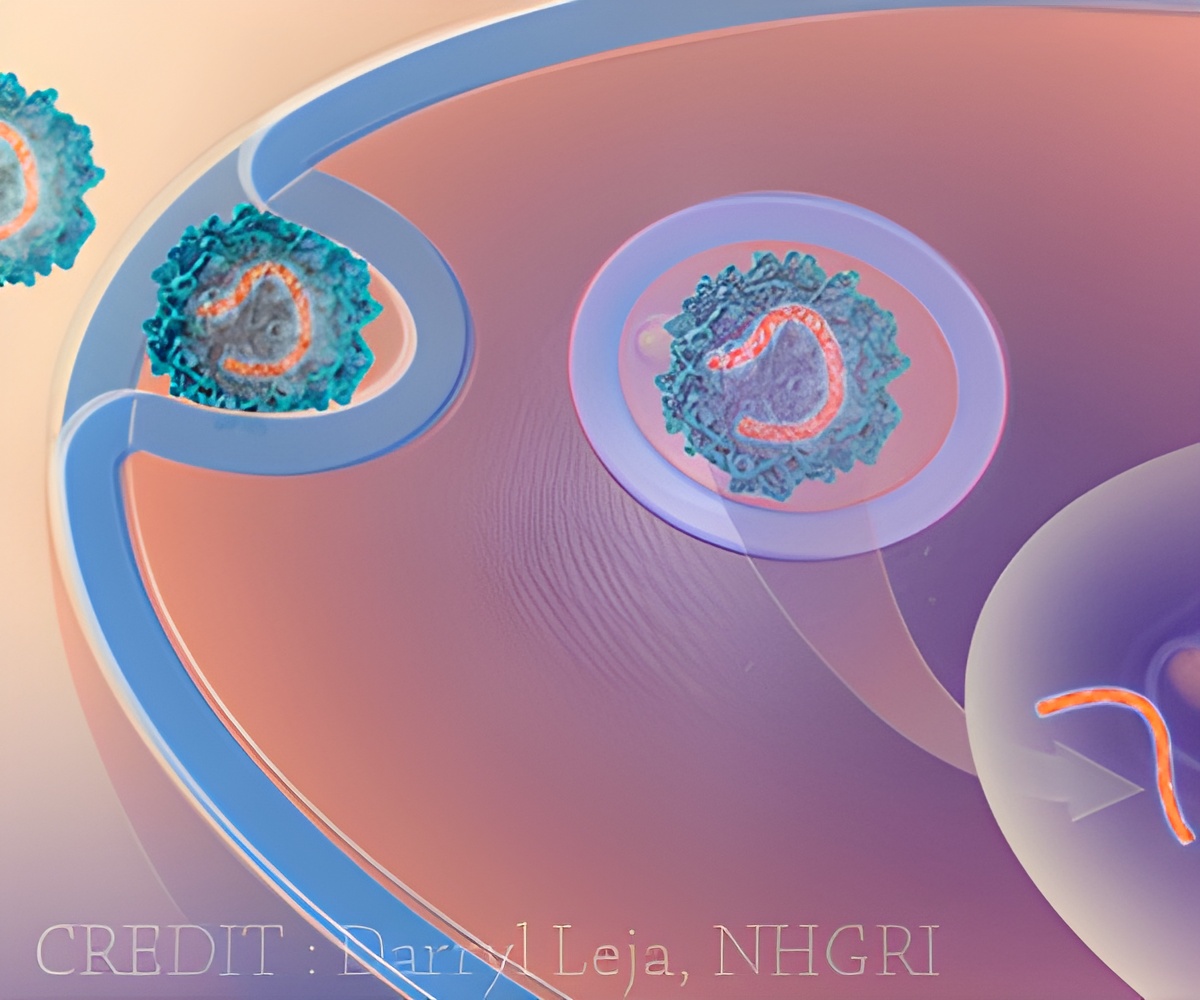

‘A vector developed from a foamy retrovirus is used in gene therapy to treat SCID-X1 by replacing defective genes with repaired ones.’

Trobridge and his team report their development in Scientific Reports, an online open-access journal produced by the Nature Publishing Group. The team is translating their findings into a stem cell gene therapy to target a life-threatening immunodeficiency in newborns called SCID-X1, also known as "Boy in the Bubble Syndrome." Gene therapy holds potential for treating genetic diseases by replacing defective genes with repaired ones. It has shown promise in clinical trials but has also been set back by difficulties delivering genes, getting them to work for a long time and safety issues. A joint French and English trial, for example, successfully treated 17 out of 20 patients with SCID-X1 only to see five of them develop leukemia.

Trobridge and his colleagues are using a vector developed from a foamy retrovirus, so named because it appears to foam in certain situations. Unlike other retroviruses, they don't normally infect humans. They also are less prone to activate nearby genes, including genes that might cause cancer.

Retroviruses are a natural choice for gene therapy because they work by inserting their genes into a host's genome. With an eye toward making the vector safer, the Trobridge team altered it to change how it interacts with a target stem cell so it would insert itself into safer parts of the genome. They found that it integrated less often near potential cancer-causing genes.

"Our goal is to develop a safe and effective therapy for SCID-X patients and their families," said Trobridge. "We've started to translate this in collaboration with other scientists and medical doctors into the clinic." He predicted that the therapy could be ready for clinical trials within five years.

Advertisement