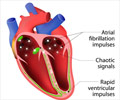

Gene therapy aims to correct the most common complication following a heart attack, arrhythmias.

‘Transfer of a single gene, Connexin43, which electrically couples non-excitable cells to undamaged heart cells dramatically reduces post-infarction arrhythmias.’

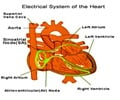

Their paper, "Overexpression of Cx43 in Cells of the Myocardial Scar: Correction of Post-infarct Arrhythmias Through Heterotypic Cell-Cell Coupling," was published in Nature Scientific Reports. The team was led by Bernd Fleischmann, M.D., professor and chairman of the Institute of Physiology at the University of Bonn, with whom Kotlikoff has collaborated for almost 30 years. Their work demonstrates a dramatic reduction of post-infarction arrhythmias in mice following the transfer of a single gene, Connexin43, which electrically couples non-excitable cells to undamaged heart cells.

"We've created a bridge for the electrical signal," Fleischmann said. "We suspected it would work. We suspected that the cells we were putting in were actually working in this way, but it is really exciting."

The group's excitement is tempered by the reality that these are mouse hearts, with induced, regularly shaped infarctions that are fractions of the size of those in humans. The spatial difference, Kotlikoff said, is not trivial.

"Whether this will work in humans, or even in larger animals, that's still a question and my colleagues in Germany are pursuing this," Kotlikoff said.

Advertisement

"It could be a very simple medical procedure," Kotlikoff said. "One could imagine a relatively noninvasive procedure in which the gene is introduced through a catheter, resulting in long term protection."

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert