Researchers at the Medical College of Georgia have identified genes that protect the heart from damage caused by chemotherapy.

Researchers at the Medical College of Georgia have identified genes that protect the heart from damage caused by chemotherapy.

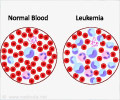

The study was conducted by Dr. Hernan Flores-Rozas, MCG cancer researcher and Dr. Ling Xia, graduate exchange student from China’s Wuhan University, who found a series of genes that protect cells from the powerful, common chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin, a drug that can also destroy the heart.Doxorubicin is widely used to treat solid tumours from breast cancer to prostate and ovarian cancer. A slightly modified version, daunorubicin, is a powerful fighter of leukemia and lymphoma and often is used in children.

“We found a series of genes that are very important for cell survival in the face of doxorubicin,” says Dr. Flores-Rozas.

“At the moment you start inactivating these genes, the cells become very sensitive and don’t grow any more. So now we know which genes we need to inactivate in the cell to make it very sensitive to the drug.”

Heart cells, called cardiomyocytes, can commit suicide, or apoptosis when chemotherapy ends. The result is dilative cardiomyopathy, in which the heart becomes a boggy organ that can no longer pump blood out to the body.

Damage can even show up years after treatment, and there is no known way to prevent or treat it, short of a heart transplant.

As a part of their research the two boffins conducted studies in relatively simple yeast cells from Dr. Anil Cashikar’s yeast knockout collection.

Yeast, which have about 6,000 genes compared to humans’ 30,000, are good models for study of human cells because they include the same basic cellular functions such as replication, DNA repair, signalling and even cell death.

They found 71 genes that conveyed varying degree of protection from doxorubicin.

“The cell does not have a unique mechanism to protect from doxorubicin; it’s a very complex response. Some genes protect better than others. But in the absence of some of these genes, the cells will die from exposure to the drug,” says Dr. Flores-Rozas.

The genes may even protect cancer and cardiac cells differently, he says noting one way doxorubicin stops cancer cells is by preventing their classic rapid division. Cardiac cells, on the other hand, don’t divide. Still there’s some common ground between the cells when it comes to protection. Cardiac cells have been known to use heat shock proteins to protect themselves from toxic injuries. This enables proteins made by cells to continue to function properly.

“If you have activated heat shock response, you have more activate proteins. If you have proteins that don’t function, the cell is eventually going to die,” says Dr. Flores-Rozas.

They already are looking at their function and expression in cancer and cardiac cells normally and when exposed to doxorubicin.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the study is published in the Dec. 1 issue of Cancer Research.

Source-ANI

LIN/P