Genomic profiling can be readily integrated into the routine clinical workflow for children with brain tumors and can improve brain tumors treatment.

‘BRAF-inhibitors such as dabrafenib, which are currently undergoing clinical trials for treating pediatric gliomas, are likely to be more effective against LGGs than HGGs.’

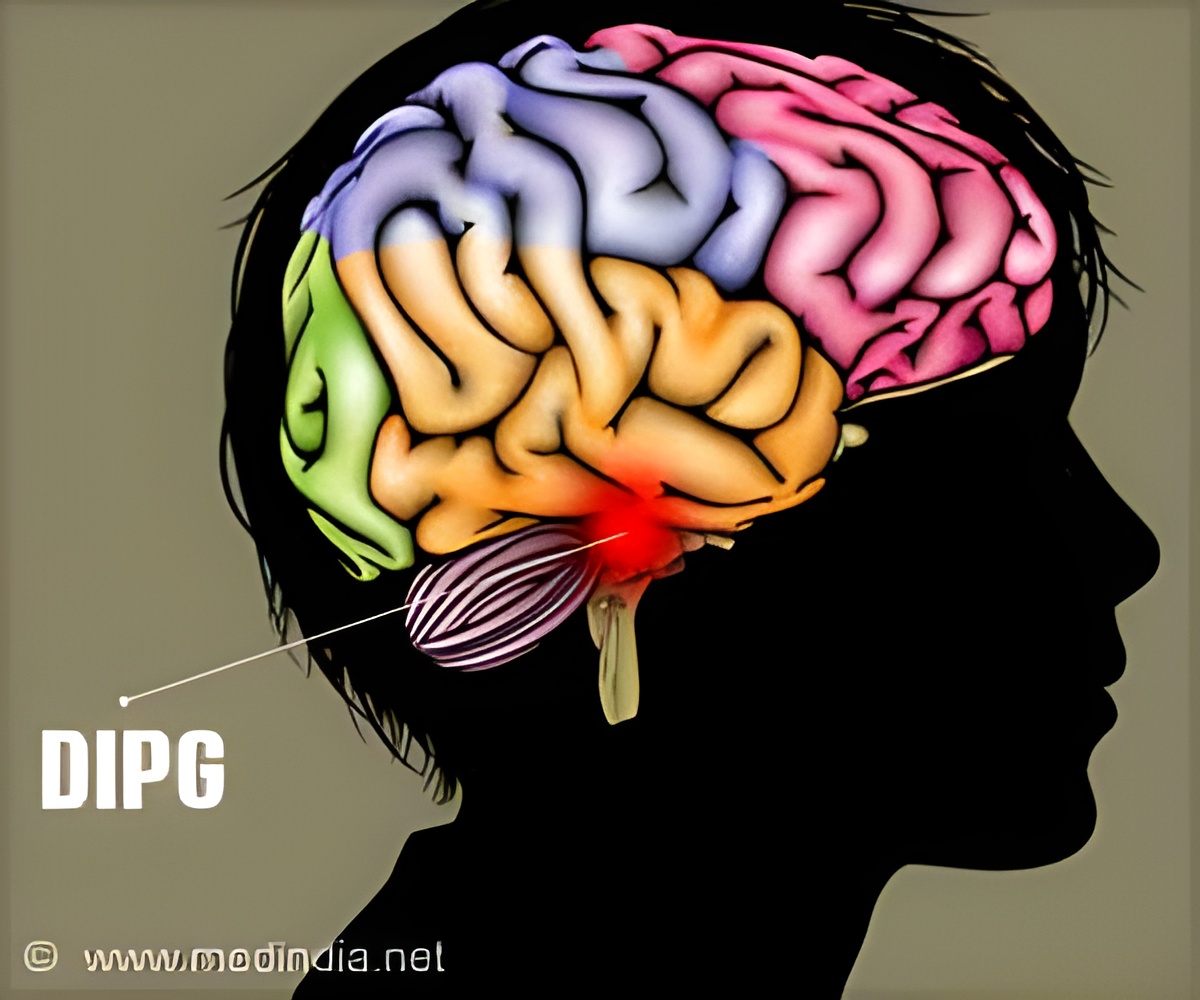

"This study further demonstrates that genomic profiling can be readily integrated into the routine clinical workflow for children with brain tumors," says corresponding author Shakti Ramkissoon, associate medical director at Foundation Medicine, a genomic profiling company based in Cambridge, MA. "We hope that the collection of objective genomic data will one day become ’standard of care’ for children with brain tumors."Pediatric gliomas are a diverse collection of brain tumors affecting children that arise from glial cells in the brain and spinal cord. Despite their diversity, pediatric gliomas can be categorized into two broad classes: low-grade gliomas (LGGs) and high-grade gliomas (HGGs), with LGGs more benign and less malignant than HGGs. Nevertheless, treatment options for both LGGs and HGGs are limited, and the long-term prognosis for children with malignant gliomas is not good. Anything that can improve this prognosis is thus to be welcomed.

With this aim in mind, Ramkissoon and a team of scientists from Foundation Medicine and several universities and medical centers in the US conducted genomic profiling of 125 LGGs and 157 HGGs taken from children varying in age from less than one to 18. To do this, they employed a technique termed hydridization-captured, ligation-based sequencing. This involves extracting DNA from each tumour sample and then introducing it to a chip covered in short strands of synthetic DNA able to capture sequences from 315 cancer-related genes and 28 genes commonly rearranged in cancer.

Captured DNA is then sequenced on the chip to determine which of these genes are altered and how they are altered. These alterations can include mutations to single genes, where DNA sequences are rearranged, deleted or inserted, and the fusing together of several genes.

Ramkissoon and his team detected genetic alterations in 96% of the tumor samples, with the most frequently altered genes differing between LGGs and HGGs. They found that genes known as BRAF, FGRFR1 and NF1 were most frequently altered in LGGs, whereas genes known as TP53 and H3F3A, together with NF1 again, were most frequently altered in HGGs. Not only does this finding show that genomic profiling can distinguish between different gliomas, but it also confirms that genomic profiling can help identify the most effective treatments for those different gliomas.

Advertisement

Thus this study shows that BRAF-inhibitors such as dabrafenib, which are currently undergoing clinical trials for treating pediatric gliomas, are likely to be more effective against LGGs than HGGs. It also shows that targeting H3F3A mutations could offer an effective way to treat HGGs.

Building on this work, Ramkissoon and his team are next planning to conduct a genomic profiling study of a type of glioma known as a glioblastoma in young adults, aged between 18 and 40.

"Pediatric gliomas represent a truly unmet clinical need in oncology. This work demonstrates that molecular profiling of these tumors provides potential therapeutic opportunities for these patients, including targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors," says Priscilla Brastianos, director of the Central Nervous System Metastasis Program at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, who is a section editor of The Oncologist and was not involved in the study.

Source-Eurekalert