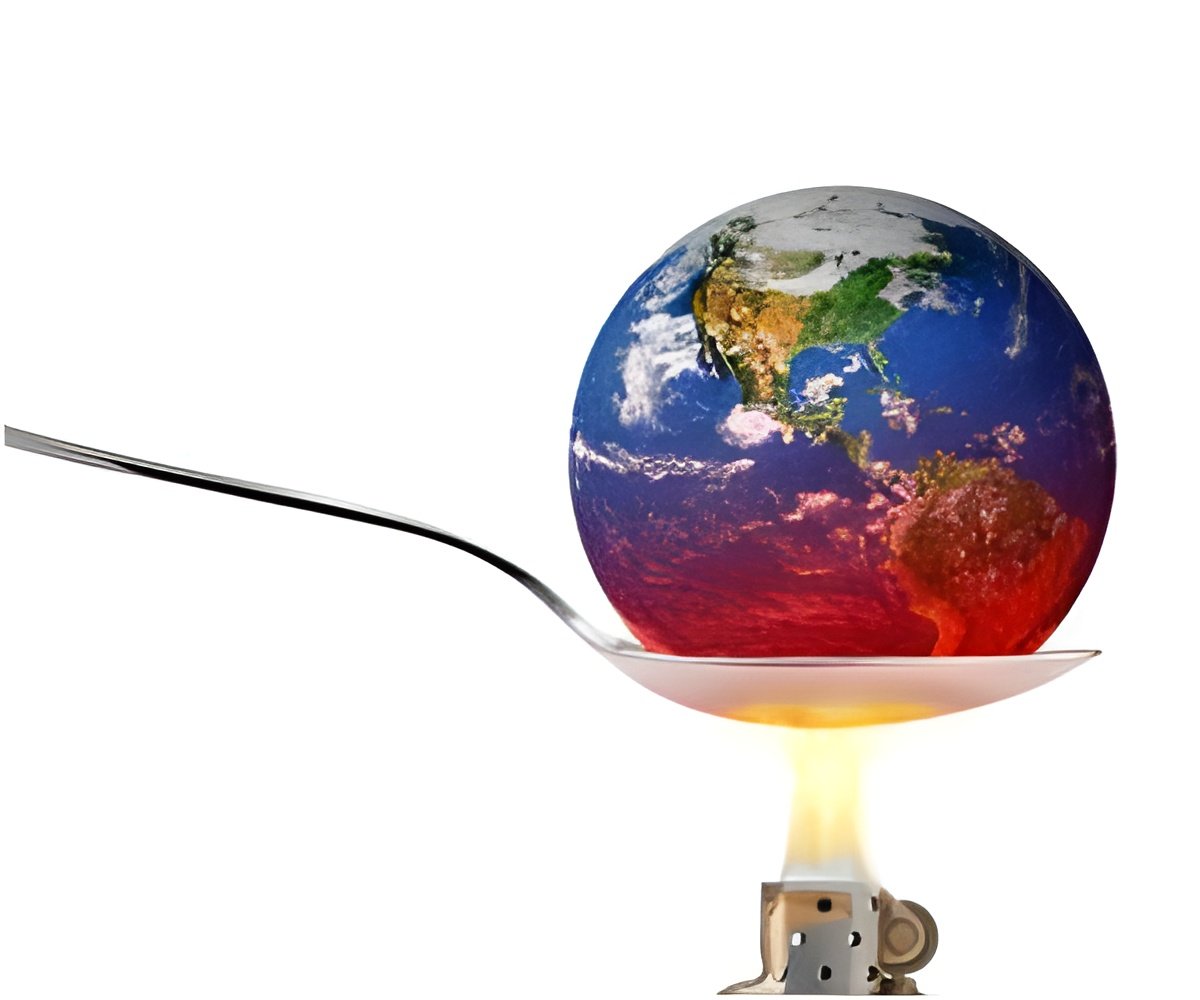

Tropical regions will see 10 percent heavier rainfall extremes, with every 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature, with possible impacts for flooding in populous regions.

Extreme precipitation in the tropics comes in many forms: thunderstorm complexes, flood-inducing monsoons and wide-sweeping cyclones like the recent Hurricane Isaac.

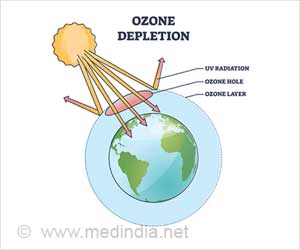

Global warming is expected to intensify extreme precipitation, but the rate at which it does so in the tropics has remained unclear - until now.

"The study includes some populous countries that are vulnerable to climate change," said Paul O'Gorman, the Victor P. Starr Career Development Assistant Professor of Atmospheric Science at MIT, "and impacts of changes in rainfall could be important there."

O'Gorman found that, compared to other regions of the world, extreme rainfall in the tropics responds differently to climate change.

"It seems rainfall extremes in tropical regions are more sensitive to global warming. We have yet to understand the mechanism for this higher sensitivity," O'Gorman said.

Advertisement

"That's not long enough to get a trend in extreme rainfall, but there are variations from year to year. Some years are warmer than others, and it's known to rain more overall in those years," O'Gorman said.

Advertisement

Looking through the climate models, which can simulate the effects of both El Nino and global warming, O'Gorman found a pattern. Models that showed a strong response in rainfall to El Nino also responded strongly to global warming, and vice versa. The results, he said, suggest a link between the response of tropical extreme rainfall to year-to-year temperature changes and longer-term climate change.

O'Gorman then looked at satellite observations to see what rainfall actually occurred as a result of El Nino in the past 20 years, and found that the observations were consistent with the models in that the most extreme rainfall events occurred in warmer periods.

Using the observations to constrain the model results, he determined that with every 1 degree Celsius rise under global warming, the most extreme tropical rainfall would become 10 percent more intense - a more sensitive response than is expected for nontropical parts of the world.

"Unfortunately, the results of the study suggest a relatively high sensitivity of tropical extreme rainfall to global warming," O'Gorman says. "But they also provide an estimate of what that sensitivity is, which should be of practical value for planning."

Results from the study are published online this week in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Source-ANI