Patients with type 1 diabetes are unable to produce the hormone insulin. Reprogramming the liver cells can give rise to the pancreas by altering gene activity.

‘Reprogramming the liver cells can give rise to the growth of pancreatic cells which may help diabetes patients.’

A way to provide a lasting help to the afflicted may be to grow new pancreatic cells outside of the body. MDC group leader and researcher Dr. Francesca has been pursuing the idea of reprogramming liver cells to become pancreatic cells. Dr. Spagnoli's team has now succeeded in thrusting liver cells into an "identity crisis" -- in other words, to reprogram them to take on a less specialized state -- and then stimulate their development into cells with pancreatic properties.Promising success in animal experiments

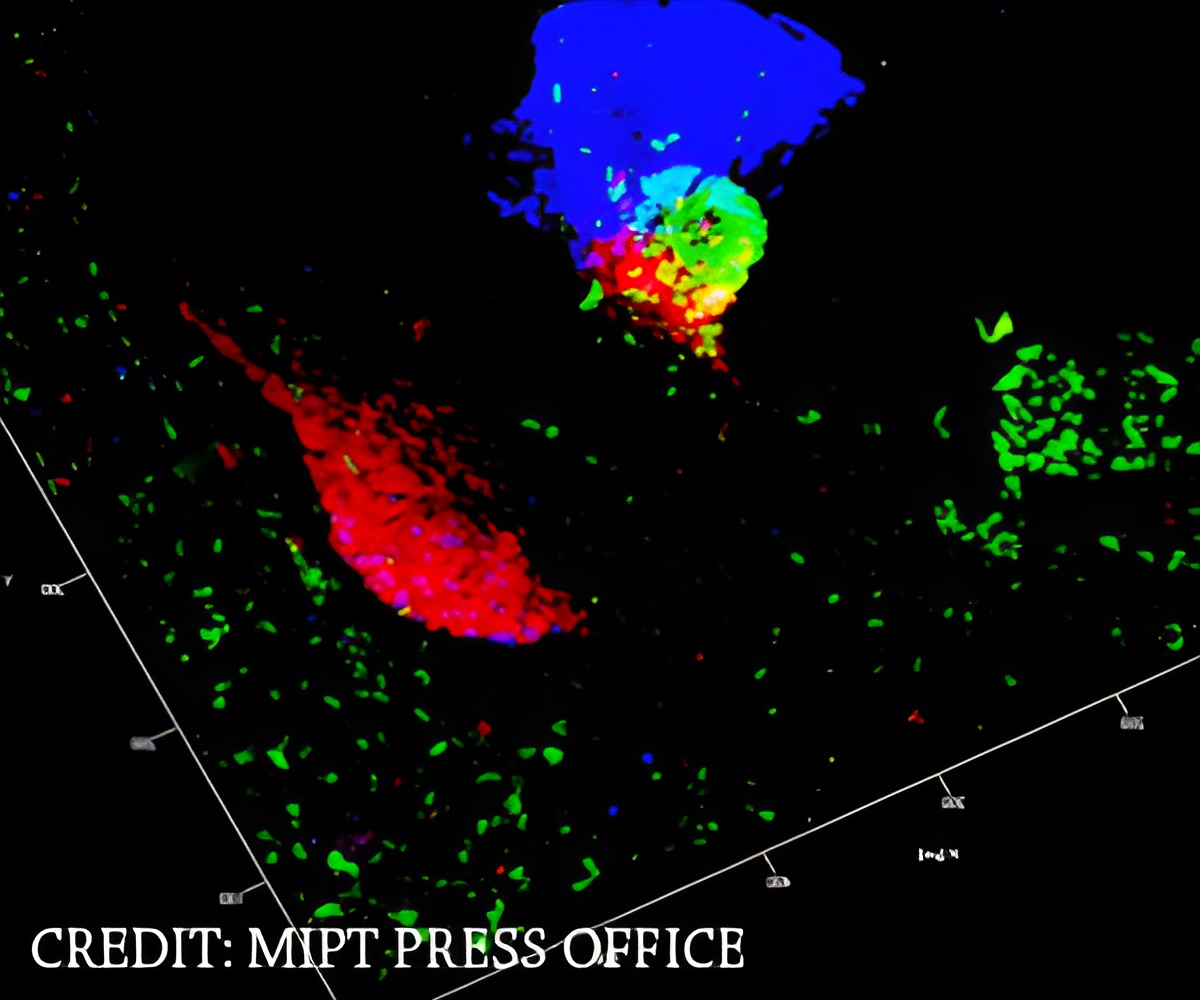

A gene called TGIF2 plays a crucial role in the process. TGIF2 is active in the tissue of the pancreas but not in the liver. For the current study Dr. Nuria Cerda Esteban, at the time a PhD student in Dr. Spagnoli's lab, tested how cells from mouse liver behave when they are given additional copies of the TGIF2 gene.

In the experiment, cells first lost their hepatic (liver) properties, then acquired properties of the pancreas. The researchers transplanted the modified cells into diabetic mice. Soon after this intervention, the animals' blood glucose levels improved, indicating that the cells indeed were replacing the functions of the lost islet cells. The results bring cell therapies for human diabetic patients one step closer to reality.

The obvious next step is to translate the findings from the mouse to humans. The Spagnoli lab is currently testing the strategy on human liver cells in a project funded in 2015 by the European Research Council. "There are differences between mice and humans, which we still have to overcome," Spagnoli says. "But we are well on the path to developing a 'proof of concept' for future therapies."

Advertisement