Scientists have found that the shape of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori is critical in its ability to colonize the stomach.

For the first time, researchers at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center have found that, at least when it comes to H. pylori's ability to colonize the stomach, shape indeed matters.

Microbiologist Nina Salama and colleagues are the first to demonstrate that the bug's helical shape helps it set up shop in the protective gelatin-like mucus that coats the stomach.

Such bacterial colonization - present in up to half of the world's population - causes chronic inflammation that is linked to a variety of stomach disorders, from chronic gastritis and duodenitis to ulcers and cancer.

"By understanding how the bug colonizes the stomach, we can think about targeting therapy to prevent infection in the first place," said Salama.

Specifically, the researchers discovered a group of four proteins that are responsible for generating H. pylori's characteristic curvature.

Advertisement

"Having these mutant strains in hand allowed us to test whether the helical shape is important for H. pylori infection, and it is. All of our mutants had trouble colonizing the stomach and were out-competed by normal, helical-shaped bugs," Salama said.

Advertisement

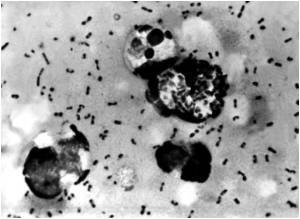

The researchers also discovered a novel mechanism by which these proteins drive the organism's shape, in essence acting like wire cutters on a chain-link fence to strategically snip certain sections, or crosslinks, of the bacterium's mesh-like cell wall.

"The crosslinks preserve the structural integrity of the bacterial wall, but if certain links are cleaved or relaxed by these proteins, it allows the rod shape to twist into a helix," Salama said.

Mutant forms of H. pylori that lack these proteins are misshapen, ranging from rods to crescents, which hampers their ability to bore through or colonize the stomach lining.

"We found that the bacteria that lost their normal shape did not infect well, and so we know that if we inhibit normal shape we can slash infection rates," Salama said.

The findings have been reported in Cell.

Source-ANI

RAS