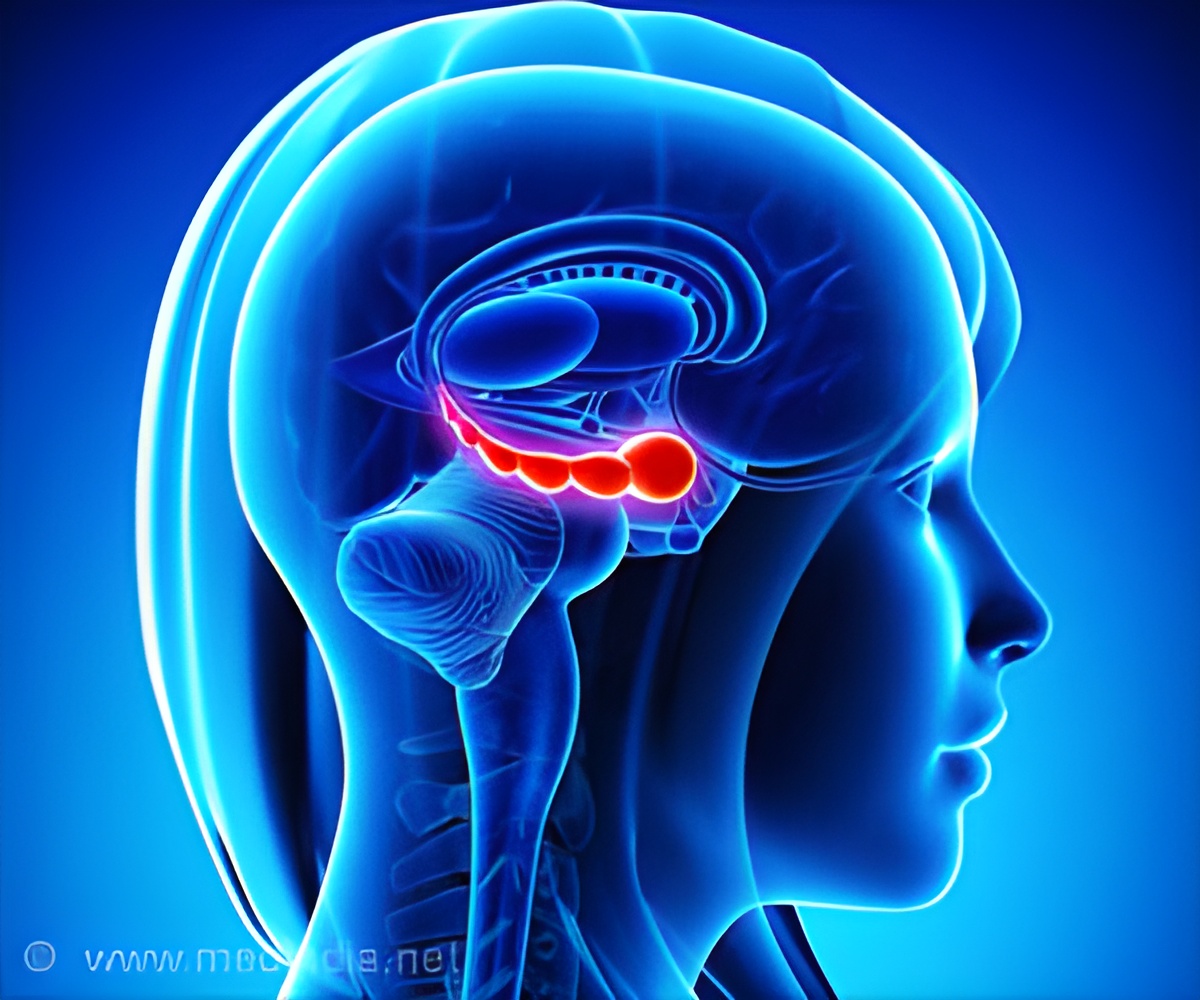

Individuals with recurrent depression have a significantly smaller hippocampus compared to those with a healthy mental state, says a new BMRI study.

Findings of the study also show that individuals whose major depression started before the age of 21 years possessed a smaller hippocampus. However, individuals who had not suffered more than one episode of major depression did not have a smaller hippocampus than the healthy subjects.

The study was conducted by ENIGMA researchers which included a group of researchers from the Brain and Mind Research Institute (BMRI) at the University of Sidney in Australia.

According to the researchers, the study points to a need to treat depression when it first emerges - especially in adolescents and young adults.

The study examined magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans of nearly 9,000 individuals which included 1,728 with major depression and 7,199 healthy individuals. The researchers also had access to clinical records of the individuals with depression.

Jim Lagopoulos, an associate professor at the University, says the study gives new insights into the mechanisms that might underlie depression.

According to him, the first reason we are not greatly aware of this is the lack of researches with sufficiently large numbers of participants. Secondly, the disease and treatments vary widely and there are also complicated interactions between brain structure and some of the clinical characteristics.

“Particularly in teenagers and young adults, to prevent the brain changes that accompany recurrent depression," Hickie adds.

He points out that it also important to conduct studies to find out methods to track changes in hippocampus size over time in individuals with depression.

“Findings from such studies may help explain the question of cause and effect whether hippocampal abnormalities result from prolonged duration of chronic stress, or represent a vulnerability factor for depression, or both," he suggests.

Lagopoulos also says that the BMRI research backs the "neurotrophic hypothesis of depression," the concept that individuals with chronic depression have certain differences in brain biology - such as sustained higher levels of glucocorticoid - that reduce the size of the brain.

References:

Molecular Psychiatry advance online publication 30 June 2015; doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.69http://sydney.edu.au/study.html

http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/

http://enigma.lbl.gov/

Source-Medindia