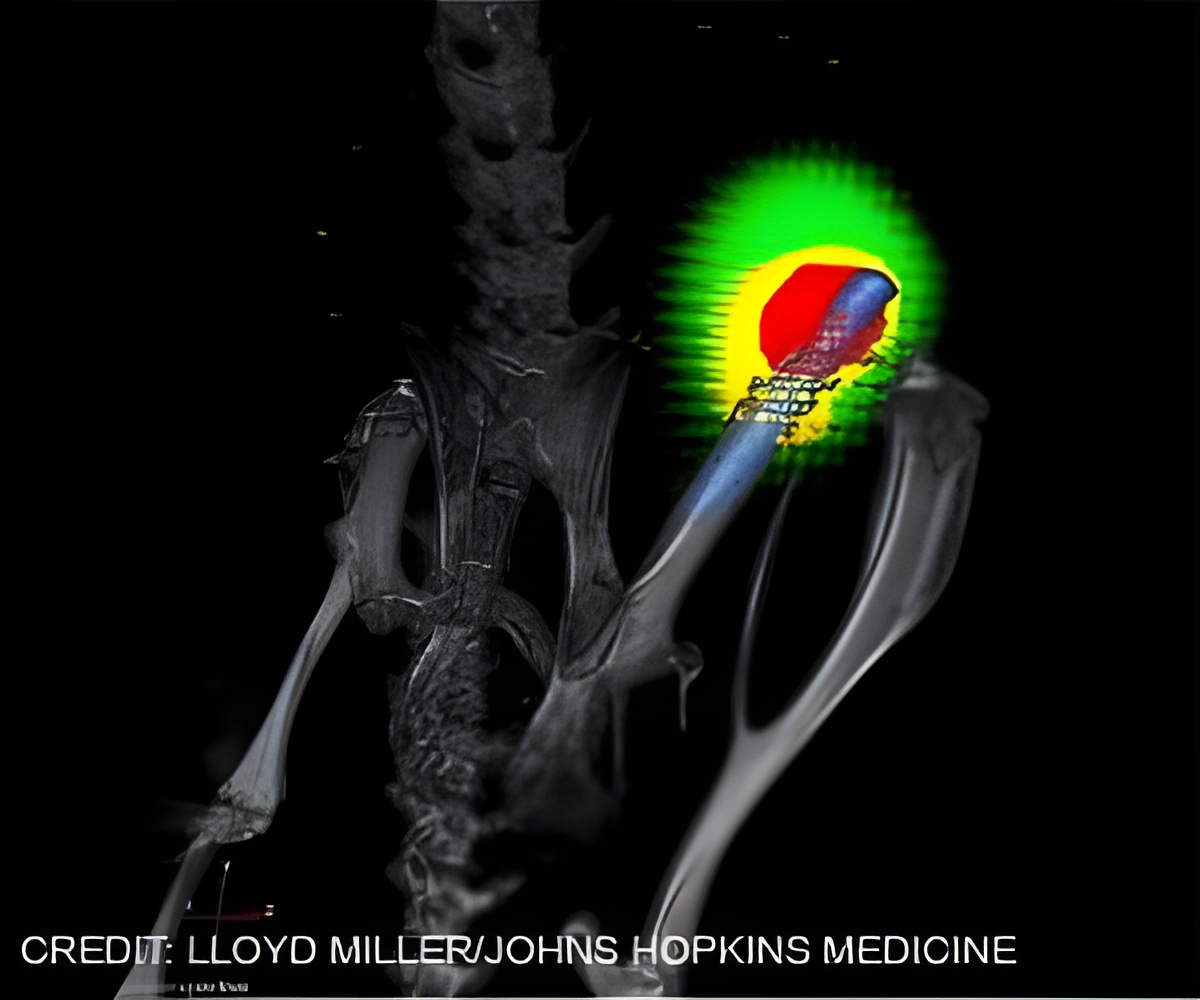

A novel coating made with antibiotic-releasing nanofibers has the potential to prevent serious bacterial infections related to total joint replacement surgery.

- Infections are a known complication of implanting artificial hip, knee and shoulder joints.

- Infections can become chronic making treatment difficult which warrants removal of the implanted prostheses.

- A new coating made of nanofiber mesh has shown promising results against serious bacterial infections.

- The new material can release multiple antibiotics in a strategically timed way for an optimal effect.

Out of the 1 million hip and knee replacement surgeries every year in the U.S., an estimated 1% to 2% develop infections linked to the formation of biofilms -- layers of bacteria that adhere to a surface, forming a dense, impenetrable matrix of proteins, sugars and DNA.

In some people, low-grade chronic infections can last for months, causing bone loss that leads to implant loosening and ultimately failure of the new prosthesis. These chronic infections may not respond to treatment and patients placed on long courses of antibiotics before a new prosthesis can be implanted. The cost per patient often exceeds $100,000 to treat a biofilm-associated prosthesis infection.

The study was conducted in mice by scientists at the Johns Hopkins University show and the report on the study, published online in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The experiment was conducted on the rodents' knee joints, but, the researchers say, the technology would have "broad applicability" in the use of orthopedic prostheses, such as hip and knee total joint replacements, as well pacemakers, stents and other implantable medical devices.

"We can potentially coat any metallic implant that we put into patients, from prosthetic joints, rods, screws and plates to pacemakers, implantable defibrillators and dental hardware," says co-senior study author Lloyd S. Miller, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of dermatology and orthopedic surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

"Rifampin has excellent anti-biofilm activity but cannot be used alone because bacteria would rapidly develop resistance," says Miller. The coatings released vancomycin, daptomycin or linezolid for seven to 14 days and rifampin over three to five days. "We were able to deploy two antibiotics against potential infection while ensuring rifampin was never present as a single agent," Miller says.

The team then used each combination to coat titanium Kirschner wires -- a type of pin used in orthopaedic surgery to fix bone in place after wrist fractures -- inserted them into the knee joints of anesthetized mice and introduced a strain of Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterium that commonly causes biofilm-associated infections in orthopaedic surgeries.

After a period of 14 days, none of the mice that received pins with either linezolid-rifampin or daptomycin-rifampin coating had detectable bacteria either on the implants or in the surrounding tissue.

"We were able to completely eradicate infection with this coating," says Miller. "Most other approaches only decrease the number of bacteria but don't generally or reliably prevent infections."

The new coating not only prevented infection, but the bone loss often seen near infected joints, which creates the prosthetic loosening in patients, had also been completely avoided in animals that received pins with the antibiotic-loaded coating.

Further research is needed to test the efficacy and safety of the coating in humans, and in sorting out which patients would best benefit from the coating.

The polymers they used to generate the nanofiber coating have already been used in many approved devices by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, such as degradable sutures, bone plates and drug delivery systems.

Source-Medindia