Synergy of sex differences in visceral fat measured with CT and tumor metabolism helps predict overall survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Belly fat affects the odds of women surviving kidney cancer but not men.

- Belly fat (abdominal visceral fat) affects the progress of kidney cancer differently for male and female patients.

- It may reduce the chance of survival for women patients.

- This also shows that a cancerous tumor develops differently in male and female patients.

Abdominal visceral fat or belly fat, affects the odds of survival for male and female kidney cancer patients, according to a recent research at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Among female kidney cancer patients with substantial abdominal fat at the time of diagnosis, half died three and half years while more than half of women with little belly fat were still alive ten years later. The same factor (belly fat) makes no difference in how long male kidney cancer patients survive.

"We're just beginning to study sex as an important variable in cancer," said senior author Joseph Ippolito, MD, PhD, an instructor in radiology at Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology at the School of Medicine. "Men and women have very different metabolisms. A tumor growing in a man's body is in a different environment than one growing inside a woman, so it's not surprising that the cancers behave differently between the sexes."

For women, how long a patient survives after diagnosis is associated not to total fat but to the distribution of body fat. Excess weight is a major risk factor for the development of kidney cancer, but it does not necessarily indicate a poor outcome.

Visceral fat and kidney cancer among women

Traditionally, body fat is measured by a person's height and weight. But not all fat is the same. Subcutaneous fats, the kind of fat that can be squeezed, may be harmless. However, the visceral fat, which lies within the abdomen and encases internal organs, has been associated with diabetes, heart disease and many kinds of cancer.

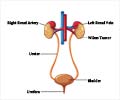

Visceral fat sits too deep inside the abdomen to be measured accurately with a tape measure around a person's waist. Instead, Ippolito and colleagues analyzed cross-sectional CT scans, which are routinely performed on people newly diagnosed with kidney cancer to measure the size of tumors and to look for metastases. Subcutaneous and visceral fat are located in different areas of the body on a CT scan, making it possible to calculate the proportion of each.

Half of the women with high visceral fat died within three and half years of diagnosis, while more than half of the women with low visceral fat were still alive after twelve years. For men, there was no correlation between visceral fat and length of survival.

"We know there are differences in healthy male versus healthy female metabolism," Ippolito said. "Not only in regard to how the fat is carried, but how their cells use glucose, fatty acids and other nutrients. So the fact that visceral fat matters for women but not men suggests that something else is going on besides just excess weight."

That "something else" could lie in the tumor cells themselves. Tumor cells prefer sugar as a fuel source, but some have more of a sweet tooth than others. A sugar-hungry tumor typically spells trouble for patients.

Using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas, the researchers analyzed the gene expression profiles of tumors from 345 men and 189 women diagnosed with kidney cancer. Both men and women were less likely to survive if their tumor cells had switched on the genes associated with consuming sugar, or glycolysis. Men whose tumor cells exhibited low glycolysis survived an average of 9 ½ years, whereas those with high-glycolysis tumors survived for only six years on average.

Having found 77 women with matched imaging and gene expression data, the analyses of visceral fat and glycolysis were combined. It was found that about a quarter of the women had a high amount of visceral fat and tumors whose glycolysis genes were significantly active. Those women survived only two years after diagnosis on average.

Notably, of the 19 women who fell into the low visceral fat and low glycolysis category, none died before the end of the study, which covered a span of 12 years. There was no group of men with a similarly rosy prognosis.

"We found there's a group of women that's doing really poorly relative to everyone else, and a group that's doing really well," Ippolito said. "Our data suggest that there is a potential synergy between the patient's visceral fat and the metabolism of their tumor. That can be a starting point to figure out how to better treat women with kidney cancer. We would not have discovered this if we had been looking at men and women together."

References:

- Gerard K. Nguyen, Vincent M. Mellnick et al. Synergy of Sex Differences in Visceral Fat Measured with CT and Tumor Metabolism Helps Predict Overall Survival in Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma, Radiology https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018171504

Source-Medindia