Gastric bypass surgery changes the gut microbes that cause rapid weight loss.

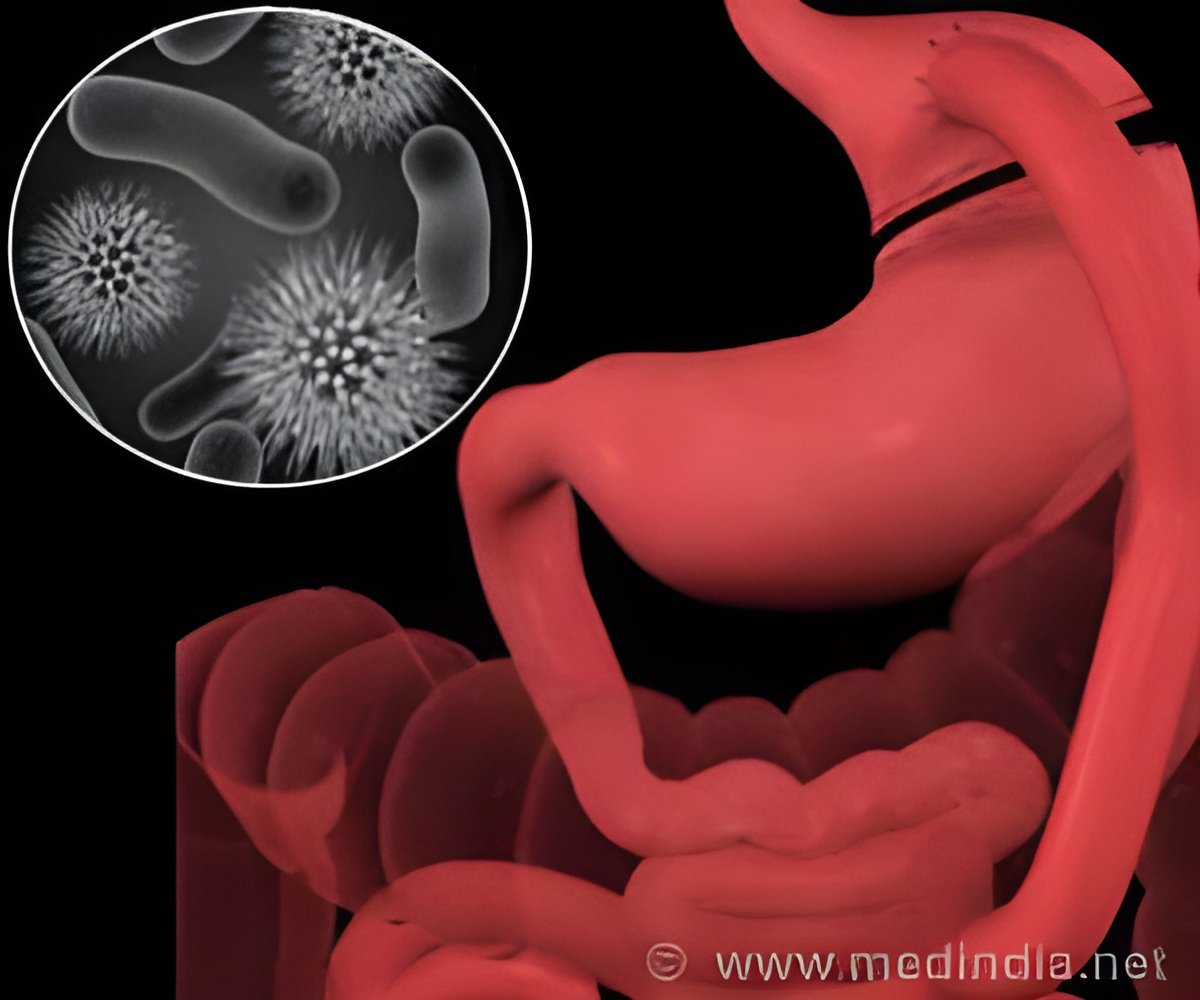

The Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is the most commonly used bariatric procedure which involves creating a pouch out of a small portion of the stomach and attaching it directly to the small intestine, bypassing a large part of the stomach and duodenum. This way the patient feels less hungry, feels full quickly, burns more calories at rest and ends up losing most of their excess fat resulting in improved glucose metabolism.

Scientists believe that these effects are not just the result of less calorie intake and absorption because of the surgery and that there is more to it. Earlier studies have shown that RYGB changes the gut microbiota, but it was not known whether the gut microbes changed because the patients got thin, or vice versa – the patients got thin because of changed gut flora.

This led Alice P. Liou at Obesity, Metabolism & Nutrition Institute and Gastrointestinal Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and her colleagues from the same Institute and also Harvard University, to find out the mechanisms linking rearrangement of the gastrointestinal tract to these metabolic changes.

In the experiment, a group of obese mice were given the RYGB procedure. They then transferred the gut microbes from RYGB-treated mice to non-operated mice. The researchers found that this resulted in weight loss (5 percent of body weight) and decreased fat mass in these non-operated mice.

They observed that following surgery, there were increased levels of gut flora, especially, species of Escherichia and Verrucomicrobia. Normally these bacteria are found at relatively low levels in healthy humans and mice.

'Our findings emphasize the importance of accounting for the influence of the trillions of microbes that inhabit our body when we consider obesity and other, complex diseases', says Peter Turnbaugh, a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University and co-author of the study.

Their next level of research is to isolate these microbes and introduce them into obese mice or people. Antibiotic treatments might help the new bacteria to stick. Despite doubts expressed by some experts, Lee Kaplan, director of the Obesity, Metabolism and Nutrition Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and another co-author of this study said, "I believe it's possible".

If confirmed in human studies, these findings could treat obesity effectively in a non-invasive way.

Reference: A. P. Liou, M. Paziuk, J.-M. Luevano, S. Machineni, P. J. Turnbaugh, L. M. Kaplan, Conserved Shifts in the Gut Microbiota Due to Gastric Bypass Reduce Host Weight and Adiposity. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 178ra41 (2013).

Source-Medindia