The shock and kill curative strategy could endanger the patient’s brain if the virus is lying dormant in the brain.

- The HIV virus can lie dormant in the brain for years.

- The shock and kill strategy, wake up the dormant viruses using latency-reversing drugs, making them vulnerable to the patient's immune system.

- But this strategy could backfire, if HIV reservoirs exist in the brain.

Shock and Kill

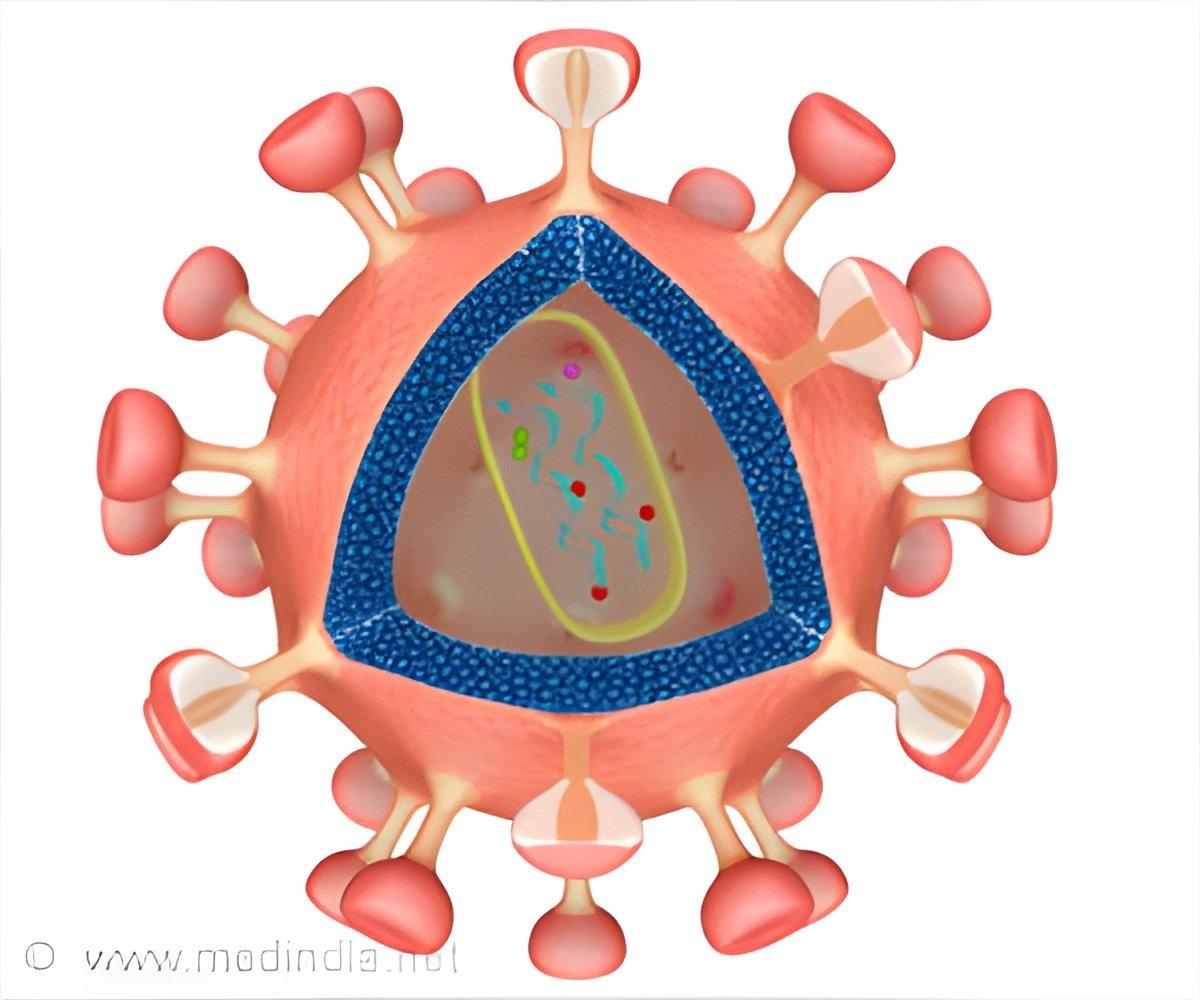

The "shock and kill," wake up the dormant viruses using latency-reversing drugs, forcing it to reveal itself and making them vulnerable to the patient's immune system.

The aim of such a strategy is to wipe out majority of infected cells, in combination with antiretroviral medicines.

This strategy could be harmful if the HIV reservoirs exist in the brain.

"The potential for the brain to harbor significant HIV reservoirs that could pose a danger if activated hasn't received much attention in the HIV eradication field," says Janice Clements, Ph.D., professor of molecular and comparative pathobiology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "Our study sounds a major cautionary note about the potential for unintended consequences of the shock-and-kill treatment strategy."

Current Study

The researchers treated three pig-tailed macaque monkeys that were infected with SIV with antiretrovirals for more than a year.

Two of the three macaques were given ingenol-B, a latency-reversing agents, to "wake up" the virus.

"We didn't really see any significant effect," Gama says, "So we coupled ingenol-B with another latency-reversing agent, vorinostat, which is used in some cancer treatments to make cancer cells more vulnerable to the immune system."

The macaques also continued their course of antiretrovirals throughout the experiment.

Encephalitis

After a 10-day course of the combined treatment, the macaques which was not given the curative treatment remained healthy. The others developed symptoms of encephalitis, or brain inflammation and blood tests were positive for SIV infection.

The researchers humanely killed the macaques, when their condition worsened and carefully removed the blood from their body.

Testing revealed SIV was still present in the brain, but only in one of the regions analyzed-the occipital cortex, which processes visual information. The affected area was very small .

Points to Remember

The results on macaques with SIV may not apply to humans with HIV.

The encephalitis could have been transient and resolved on its own.

The results signal a need for extra caution in exploring ways to remove HIV reservoirs and eradicate the virus from the body.

Source-Medindia